Conceptual Artist John Latham Transformed Books Into Art. Now His Works Are on View in New York

Artnet Gallery Network

There’s a long history of visual artists incorporating books into their work, from Duchamp in the early 20th century to Samuel Levi Jones today. But perhaps no artist is more associated with the practice than British conceptualist John Latham, who has integrated books into his paintings, assemblages, sculptures, and other works since the late 1950s.

A new exhibition on view at one of Lisson Gallery’s New York spaces, “John Latham: Skoob Works,” uses the artist’s interest in the book as a framing device to survey his long, multifarious career and the many contributions to conceptual art and theory that he made along the way.

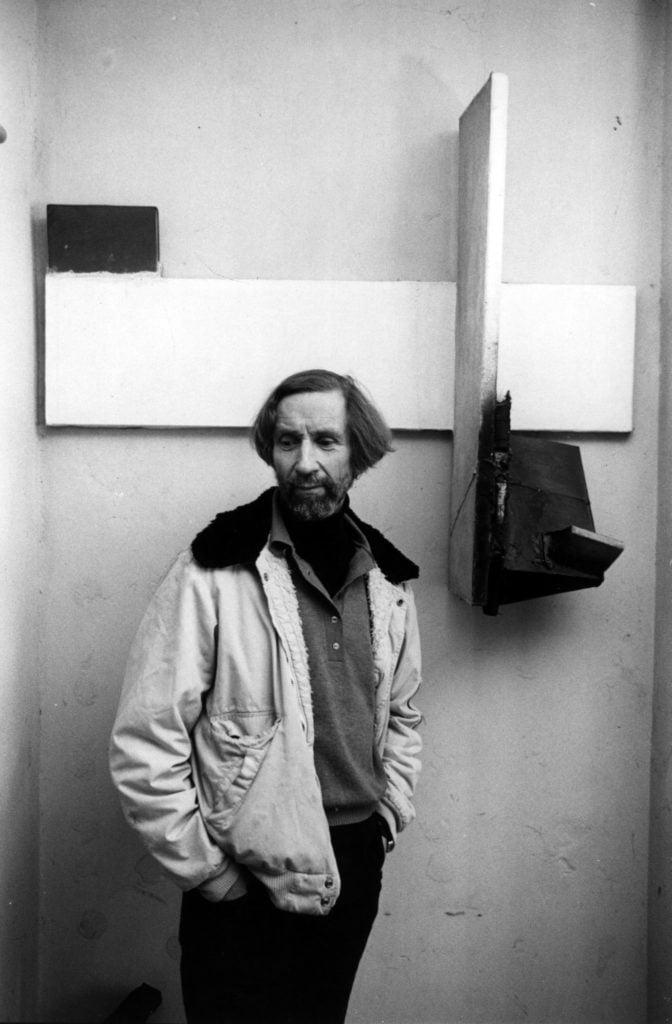

John Latham. © The John Latham Foundation. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

Latham was born in Livingstone, Northern Rhodesia (what is now Maramba, Zambia) to English parents, and he moved to the UK at an early age. He enrolled at Regent Street Polytechnic in 1946, and then the Chelsea College of Art and Design in 1947. He had his first solo show at Obelisk Gallery in London in 1954, where he showed a selection of paintings done with a spray gun—an unprecedented gesture at the time.

In the late ’50s, Latham first introduced books into his work, using plaster to adhere the object to his spray-painted canvases—such as in his 1958 work Burial of Count Orgaz where he recreated El Greco’s 1586 painting of the same name with collaged books and other found items. Soon after, he came up with the name for the work: “skoob”—“books” spelled backward—which he continued to use for decades after.

John Latham, Great Uncle Estate (1960). © The John Latham Foundation. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

The earliest works dating in the Lisson exhibition date back to the early 1960s, a time in which Latham was making large wall reliefs with books. Great Uncle Estate (1960), for instance—the largest such work the artist ever created—is a 10-foot-wide, multi-panel assemblage with patches of books arising from the canvas surface like mountains on a topographical map. Half of the volumes are positioned outward, their pages held open by wire; the other half are turned inward, leaving a mystery as to what they contain.

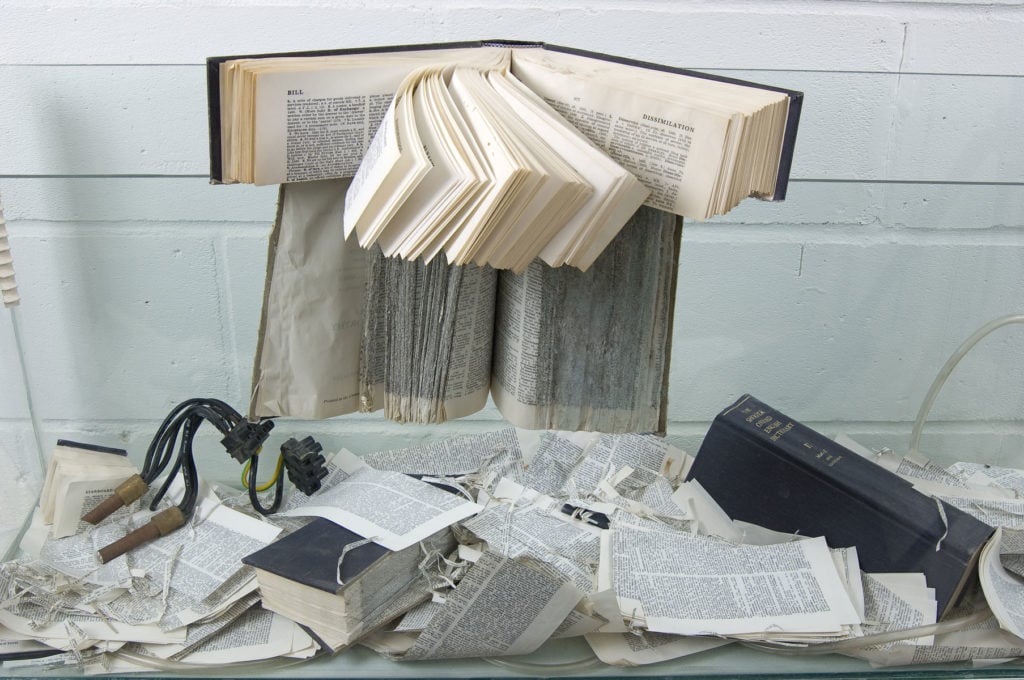

In the late ’60s and ’70s, Latham branched out to freestanding book sculptures—“skoob towers”—which were composed of old law books, encyclopedias, and popular periodicals stacked atop one another. After building these structures, he would burn them (often publicly, as he did with the Destruction in Art Symposium in London 1966).

Installation view of “John Latham: Skoob Works” (2018). © The John Latham Foundation. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

That same year, while teaching at St. Martins School of Art in London, he encouraged students to take literal bites out of Clement Greenberg’s landmark collection of critical essays, Art and Culture, then asked them to chew the pages and spit them out. Latham collected the masticated pages and fermented them in acid for a year before returning the concoction to the school. In other events, Latham installed pipes into his book structures and ran expanding polystyrene foam through them—a metaphor for the dissemination of information.

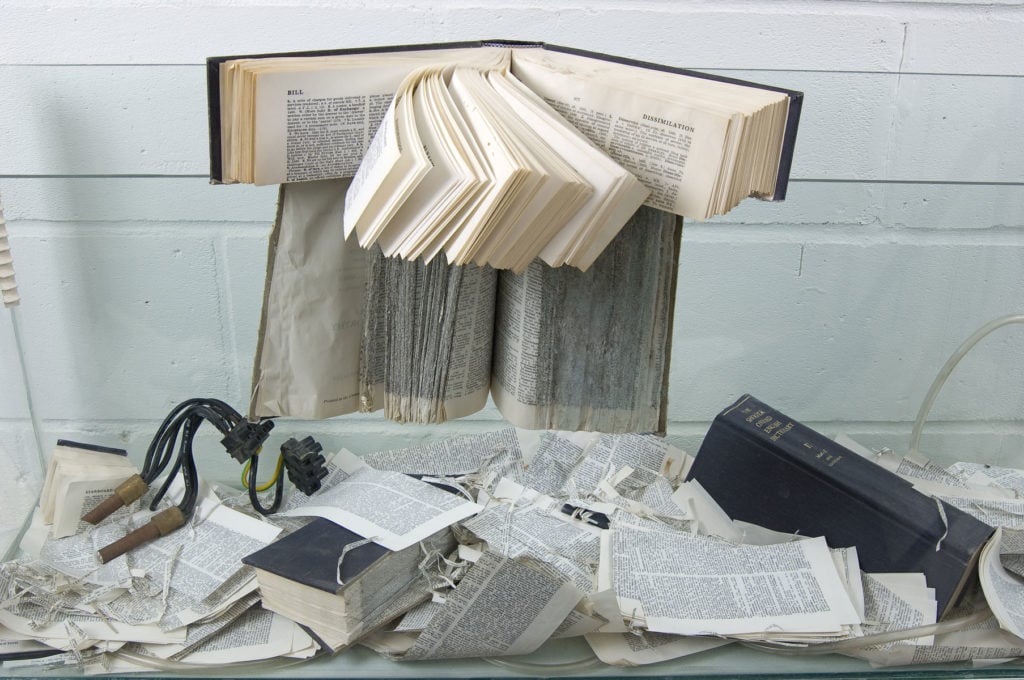

In the ’80s, Latham began a new body of sculptures in which he bisected Bibles and other liturgical texts with large panes of glass—a theme he would revisit throughout the rest of his career. In his 1988 work They’re Learning Fast, for instance, he installed a text he had written four years earlier about the British government’s inadequate art funding (“Report of a Surveyor”) in a fish tank surrounded by live fish.

John Latham, They’re learning fast (1988). © The John Latham Foundation. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

For Latham, the book symbolized a variety of ideas—institutional knowledge, the transmission of information, the limits of communication. In a sense, he was also something of an open book himself. In 2003—three years before his death in 2006 at the age of 84—he announced that his home and studio were a living sculpture and instituted an open-door policy for art students and anyone else who wanted talk art.

“John Latham: Skoob Works” is on view at Lisson Gallery in New York through June 16, 2018.