A Lyrical Japanese Abstract Expressionist in New York, Kikuo Saito Was Long Forgotten. Not Anymore.

Artnet Gallery Network

When the Japanese artist Kikuo Saito immigrated to New York in 1966 at age 27, he knew very little English. This communication barrier and his subsequent experience learning the language would prove to be transformative for him, influencing his work all the way until his death in 2016.

Many of his paintings, including those on display for the first time now at Jonathan Novak Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, feature the kind of squiggly, energetic mark-making found in the work of the Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. Saito’s marks, however, are not as purely abstract as they seem—they’re deconstructed letters, stretched and contorted beyond recognition.

“He was trying to interpret the characters of the English language as pictures and symbols,” says Dakota Sica, the director of Leslie Feely gallery, which represents Saito’s estate in New York. “He developed a method where A and B and C correlated with different colors and ideas in his paintings. There’s never any complete words; the text doesn’t combine to make something, even though your mind might want it to do that. It acts as a symbol for colors or other marks that together create the composition.”

Kikuo Saito, Golden Bees (2013). Oil on canvas, 58-3/4 x 75-5/8 in. Courtesy of Jonathan Novak Contemporary Art.

Not long after arriving in New York, Saito ingratiated himself into the tight-knit community of artists who followed in the footsteps of the Abstract Expressionists, a group that included Helen Frankenthaler, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, and Larry Poons, among others. He initially took a job as a studio assistant for Noland, stretching canvases and mixing paints, and soon after began working for Frankenthaler and Poons. Those artists’ work, as well as that of their contemporaries, had a big influence on Saito’s early paintings, which looked like rehashed color fields (though he didn’t show his paintings at this time). Ultimately, it was another set of artists and medium that helped to push Saito’s style into maturity.

In the ‘70s, as an avid follower of theater and dance, Saito began organizing performances at the La Mama Theater in the East Village—the famous downtown haunt of experimental actors, playwrights, and choreographers. It was there that he met, and eventually collaborated with, Robert Wilson—another influential figure in the painter’s development—as well as his first wife, the dancer and choreographer Eva Maier. And while Saito achieved his first real recognition for the productions he put on at La Mama, the more significant impact that the theater had on his career materialized on the canvas.

Installation view of “Kikuo Saito” at Jonathan Novak Contemporary Art. Courtesy of Jonathan Novak Contemporary Art.

“For some of his early performances with Wilson, Saito would actually paint the backdrops,” says Sica. “Instead of a scenery set, it would be a giant abstract canvas hanging behind the stage. That’s when he started employing his body when making paintings, because, when he had to paint these big backdrops, he would be walking around the canvas, adding color, adding text and images. He was also inspired by the choreography of the performances, and how the dancers and actors would move around the stage, almost as if it was a flat composition.”

After that, notes Sica, Saito’s style changed: “He began painting on both the easel and the floor. He’d move back and forth by taking the painting from the wall, putting it on the floor, and literally dancing around it with his brush.”

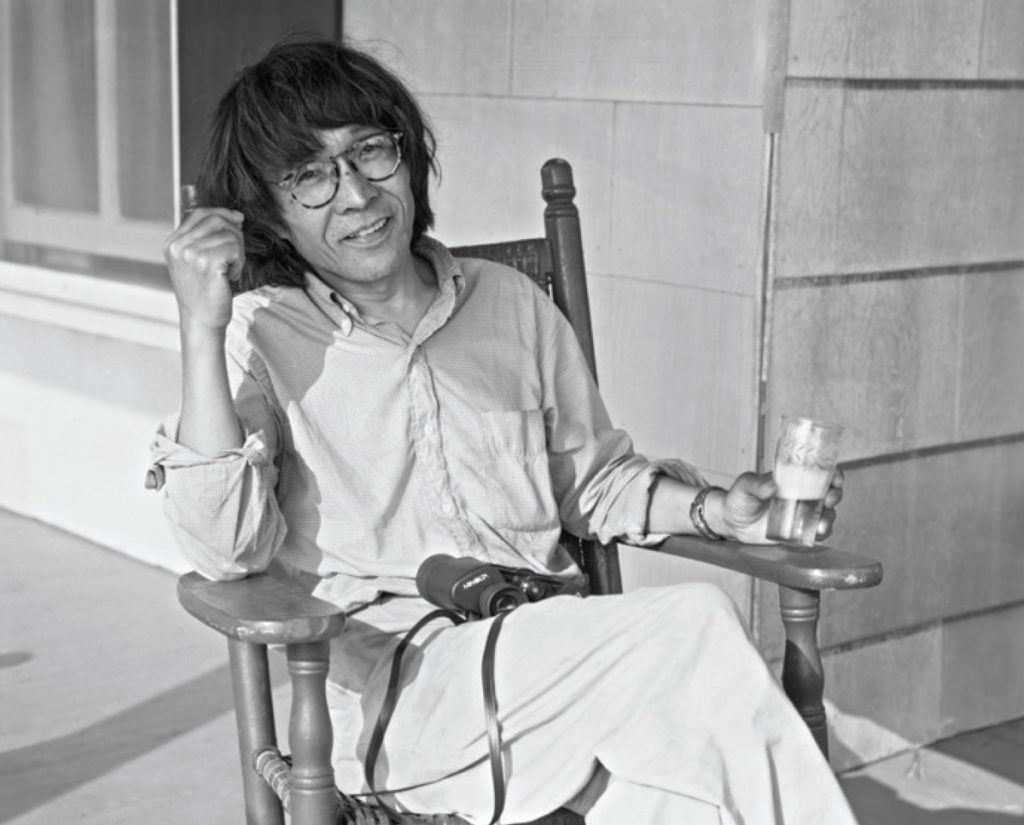

Kikuo Saito in Cape May Point, New Jersey. Courtesy of Jonathan Novak Contemporary Art. Courtesy © William Noland.

Saito quit the theater in the late ‘70s, frustrated by the production obstacles, and began focusing solely on painting, which would remain his primary occupation until he passed away last year at age 77. “Often the work done in the later period of an artist’s life is not thought to be their strongest,” says Sica. “But with Saito, it’s really the reverse. I think he made his best paintings right up until he died.”

As with so many artists who are under-appreciated in their time, Saito’s star began to rise only after his death. And though the number of his paintings still in circulation is relatively small, he left behind other contributions that will continue to shape his legacy, especially among other artists.

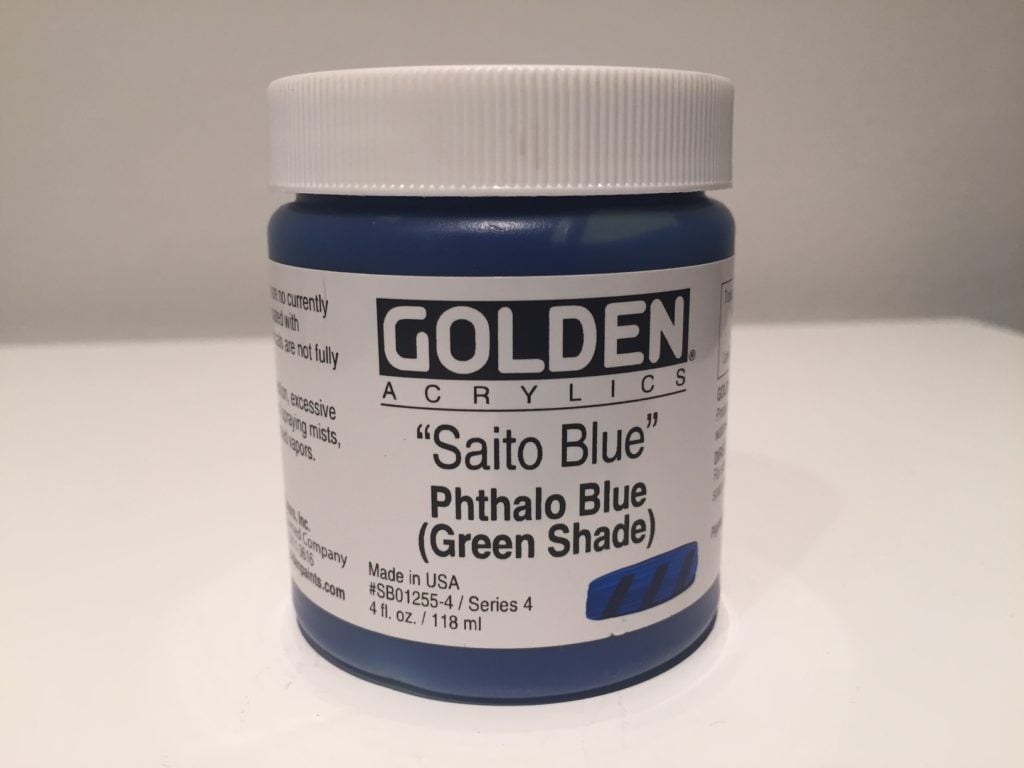

For one, he has a paint color named after him. Saito was very particular about the materials he used in his work; he exclusively used Golden Paint, and made many paintings in a particular hue of blue. After his death, the company titled that color of acrylic paint after him, rebranding it as “Saito Blue.”

“Saito Blue” paint from Golden Paints. Courtesy of Leslie Feely.

His footprints remain in New York as well. Saito’s studio and home were located in a small basement apartment in SoHo that he occupied until his death. The space, still intact and largely left untouched, is managed by his estate and his widow, Mikiko Ino, who also founded a nonprofit organization after Saito passed away. Named KinoSaito (a portmanteau of Kikuo Saito and Mikiko Ino), the organization is currently renovating an old elementary school in upstate New York, which it plans to turn it into a residency and small museum.

“It was a dream of Saito while he was still alive,” says Sica. “At one time he was a resident at the Watermill Center, and he loved the fact that that was a communal, open space; it affected him profoundly. I think he wanted to give back to artists the same way, to provide them with a similar experience.” The majority of proceeds from Saito’s painting sales go to the project.

Saito’s studio. Courtesy of Leslie Feely.

“Kikuo Saito” is on view at Jonathan Novak Contemporary Art through January 9, 2018.