Art Dealer Lukas Minssen On Taking the Helm of Germany’s Oldest Family-Run Gallery

Artnet Gallery Network

The oldest family-owned gallery in Germany is not, as one might expect, in Berlin or Frankfurt or Cologne, but rather in Dortmund, an eastern industrial city not particularly well known for arts and culture. Nevertheless, Galerie Utermann first opened its doors as a shop for gilt frames in 1853. Now, five generations later, it’s among the leading purveyors of Expressionist art.

So how does a gallery not only stay afloat but thrive for more than 160 years—and through two world wars, no less? We caught up with Lukas Minssen, who’s next up in the family leadership, for a glimpse into the gallery’s past and its future—and why it has no plans to leave its home city.

Galerie Utermann has been in business for more than 165 years, a remarkable accomplishment for any gallery, but especially one that has remained in the same family. What does that history mean to you?

With such a longstanding tradition, every member of our gallery team and every collector we engage with knows that building a strong collection takes time, that collecting is a project that might take decades if quality is of the utmost importance.

Galerie Utermann.

How did the war years affect that gallery and how did it rebuild after?

One has to imagine that our gallery building, which was also the family home, was hit by a bomb and completely destroyed. Werner Utermann, who was running the gallery then, decided that he would reestablish the space right after that terrible war. In those desperate years, if there was one you didn’t need a painting on the wall would have been it. Nevertheless, he was so determined to save the family’s tradition that he succeeded.

Since 1998 the gallery has been housed in the former executive boardroom and offices of a coal company. What should visitors to expect to see?

You should certainly not expect a white cube gallery. When the boardroom was built in 1957 it was a sign of economic strength. The space is a great example of postwar architecture and is listed as a historic landmark. We are also very happy we have a garden to call our own.

Has the gallery ever considered relocating to a more centralized city?

The reason we never really considered moving is that we advise collectors worldwide and in that case it doesn’t make a difference where you’re based—you have to be fond of traveling anyway! With art fairs like TEFAF happening so frequently being rather decentralized doesn’t affect us at all.

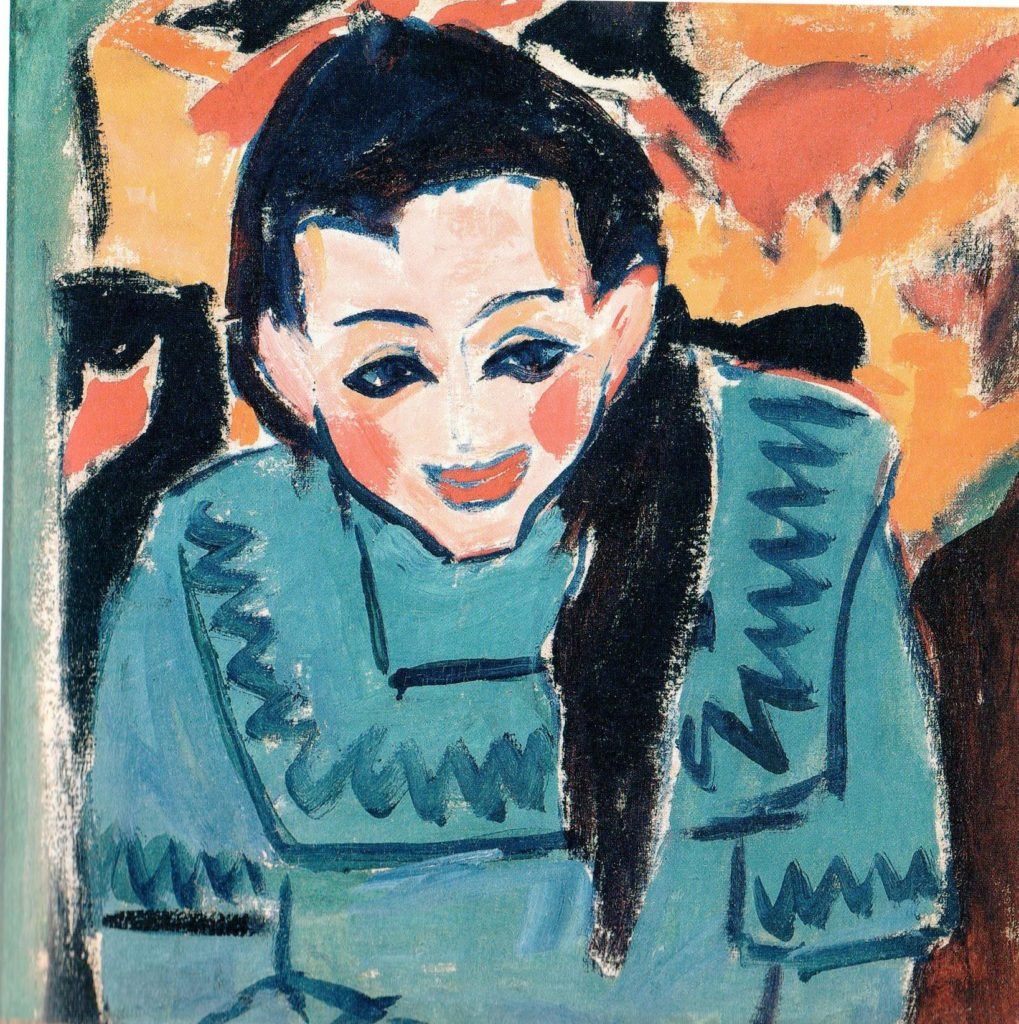

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fränzi (circa 1910). Courtesy of Galerie Utermann.

What do you think of as the defining exhibition (or two) in the gallery’s history?

That is a very tough call—there have been fabulous exhibitions at the gallery long before I was alive. If I had to choose I would say the most important exhibitions were the 1986 show celebrating the 100th birthday of August Macke, in cooperation with his estate. In 1992 we showed sculptures and drawings by Henry Moore, and in 1993 works by Pablo Picasso. Truly special also was our 2010 exhibition of Abraham David Christian, when we showed his large bronze sculptures in St. Reinoldi, a church in Dortmund that dates back to the 13th century.

The exhibition I also have to mention is our current show focusing on the two Bauhaus masters, Paul Klee and Lyonel Feininger. They were not only defining artists of the 20th century but also close friends. It is the first exhibition our gallery co-produced, in cooperation with W&K Gallery of Vienna, and it has traveled to the US and throughout Europe.

Installation view of Abraham David Christian at St. Reinoldi, 2010. Courtesy of Galerie Utermann.

Do you have any favorite stories from the gallery’s history?

My favorite story is certainly when my stepfather Wilfried Utermann rediscovered an important painting by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. He bought a 1919 still life for an upcoming Kirchner exhibition from Switzerland. When the work arrived at the gallery and was taken out of the frame, thick white paint on the back of the canvas became visible. When he saw some color underneath the white paint he had the feeling that there might be something else on the backside of the canvas. It wasn’t uncommon for Kirchner to use a canvas twice. The work was then brought to the renowned Doerner Institute in Munich to be x-rayed. It seemed that there was far more color underneath the white paint. The paint was then taken off step by step and what was found underneath was a sensational portrait of the artist’s most important model, Fränzi, dating back to around 1910. The painting is now on view at the Brücke Museum in Berlin.

You’re the family’s first art historian. How does that background affect your outlook?

My background certainly affected my studies. I had the choice between management and art history and I am very happy I chose the latter. Art History doesn’t prepare you for being an art dealer, but it gives you a solid knowledge on which to build. Nevertheless I am convinced that the only thing that really matters is true enthusiasm for art.

What’s on the horizon for the gallery?

We are thrilled about our upcoming exhibition with Vera Lutter, who is represented in every major museum in the United States but only in a few in her native Germany. She’s having a solo exhibition at LACMA in March of 2020 and we are very pleased to show her work for the first time in our gallery in September.