How the Olszewski Gallery in Warsaw Is Putting a Bright Spotlight on the Lost History of Polish Modernism

Katie White

As a young gallerist in Warsaw, Malgorzata Ciacek is an anomaly. The city’s contemporary art scene is booming, but Ciacek, the co-director of the city’s one-year-old Olszewski Gallery, has turned her attention to a subject with a lot less fanfare: Poland’s oft-overlooked Modernist era.

In fact, somewhat shockingly, the Olszewski Gallery is the only commercial gallery in Warsaw devoted to Polish art of the last century.

“There’s not much attention paid to it, which is sad. But that’s where we’re presenting ourselves,” Ciacek said, speaking also on behalf of Michal Olszewski, the former auction house specialist and adviser who owns the gallery where Ciacek works.

Recently, we caught up with Ciacek, who chatted with us about the effect of World War II on the legacy of nation’s avant-garde, the Modernist Polish artists she’s championing, and a few of Warsaw’s hidden gems.

Installation view at Olszewski Gallery, Courtesy of Klara Kopyt,

How would you explain Poland’s gallery scene and current art market?

Poland is an emerging market. Though there are many contemporary galleries in the city, ours is the first with a focus on avant-garde art made during the interwar period as well as the art of the Second World War. We’re focusing on the most important names, artists whose works were collected by major museum institutions in Poland and worldwide.

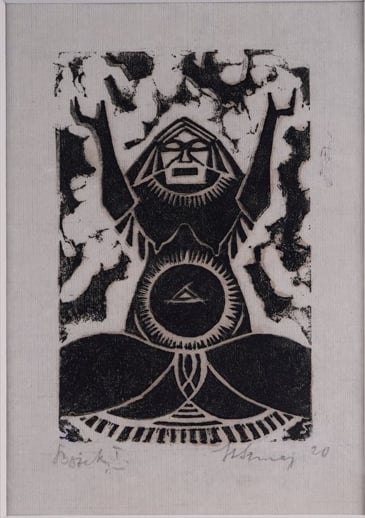

Stefan Szmaj, Deities I / Foremother (1920). Courtesy of Olszewski Gallery.

Am I right to understand that this is an under-served market?

What you find in Poland is that even many of the really well-known artists’ estates will have no representation. I’ll talk to artists’ estates or families who will have everything—the entire body of work by an artist, but they won’t know where to go with the work. Poland is distinctive, in that this is a very young market. Lots of things can be discovered, which is kind of the way we work. For these families and estates, we want to present ourselves as the gallery that is able to organize solo shows of extremely important Polish avant-garde artists. We know how to make that happen.

Your gallery space is even historical—a kind of time capsule, right?

Yes, we’re located in the city center in a former chocolate factory for Wedel, one of Poland’s oldest chocolate brands. The last company owner of the Wedel family was Jan Wedel. After the nationalization of the factory by the communists, he worked here for only a few months as an adviser, after which he was expelled and forbidden to enter the factory ever again.To get to the gallery you walk through a courtyard, then you come to us in this very old building, though our gallery is newly built-out. Though about 90 percent of Warsaw was destroyed in the Second World War, this building somehow managed to persevere. In that sense, it’s a little bit like the art we’re showing.

Courtesy of Klara Kopyt.

Who is one of these avant-garde artists we might not know, but should?

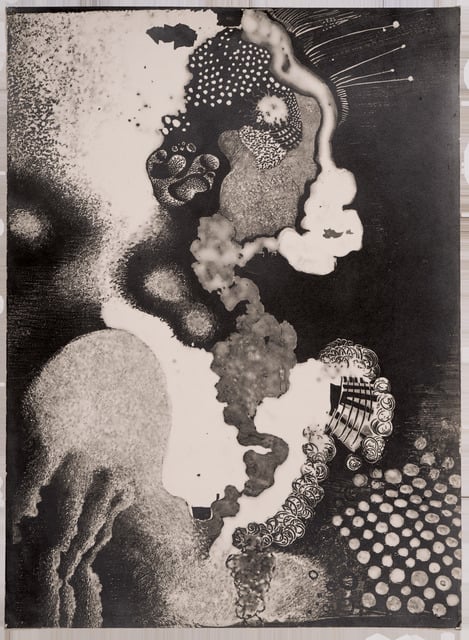

Our first exhibition, at the end of 2018, was of Karol Hiller, who was working mainly in the 1920s and ’30s. We managed to gather 17 works by him. There’s not even an estate managing his legacy. He created the technique of heliography, where he would create monochromatic images on photographic paper.

His style is somewhere between photography, painting, and graphics. He was working a little bit after Man Ray, but one can make parallels between the two. One of the works we had on view in the exhibition had been in the Tate Modern’s show “100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art.” Many people have never even heard of Hiller, even in Poland, despite him being a major, major artist.

Karol Hiller, Heliographic Composition XLI (circa 1933). Courtesy of Olszewski Gallery.

Do you have any favorite “rediscovery” stories?

The Second World War had a tremendous impact on the city, meaning there are lots of these stories still happening. Among these is Stefan Szmaj, a Polish Expressionist working in the 1920s at the same time as the German Expressionists and Die Brücke. He translated the language of Expressionism into his linocuts and was interested in ideas of Primalism and in Slavic idols and early Slavic culture.

He worked as an optician for most of his life, but he made a series of linocuts when he was in his early 20s. The story is that his wife put them in a shoebox, which is the only way they managed to survive the war, and they were discovered later. We went on to display these works dating from 1916 to 1920. We have lots of these kinds of stories in Poland.

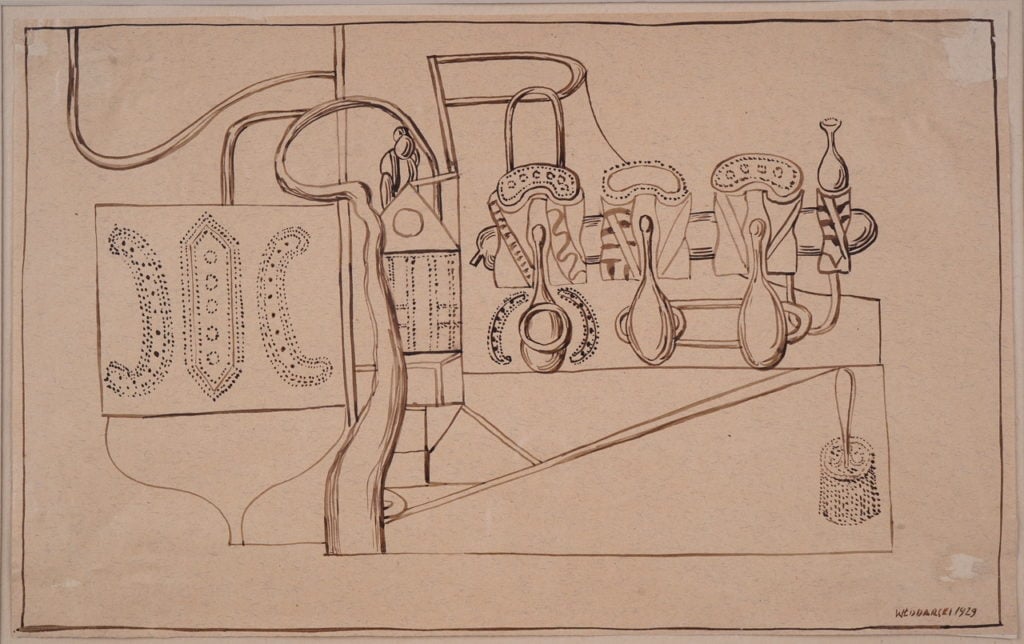

Marek Włodarski, Preparatory gouache for a Man with a Syphon painting (1926). Courtesy of Olszewski Gallery.

One of the artist’s estates you’re working with, Marek Włodarski’s, is going to be the subject of a show at Warsaw’s Museum of Contemporary Art soon, right?

Yes. Right now, with the current political situation in Poland, the Museum of Contemporary Art has become the leading institution in place of the National Museum of Warsaw. Kind of in keeping with the political climate, the Museum of Contemporary Art is organizing a solo show of works by Włodarski, mostly from the 1920s and ‘30s, but also some from after the war, in the 1950s.

Włodarski is a fascinating character. He was of Jewish descent and was born Henryk Streng in Lviv in 1903. He left Poland in 1925 to study at the Academie Moderne in Paris, a free school founded and run by Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant. Włodarski was very much inspired by Léger’s shapes and colors, but whereas Léger’s works were about machines and discoveries, Włodarski was in love with his native town’s life. He came back to his home city, and while his style is similar to Léger’s, his subjects are artisans and everyday street life, bicyclists, flower vendors, and passersby.

In the 1930s, in the lead up to the war, his aesthetic changed and became surreal. There was a sense of something bad about to happen. The dream-like images are a way of protecting himself from the oppressive reality he was living in. During the Second World War, he actually changed his name from Henryk Streng to the more Polish sounding Marek Włodarski, and he went back and changed the signature on every single one of his works just to survive.

Marek Włodarski, Cyclist (ca. 1925). Courtesy Olszewski Gallery.

When do you have a chance to promote these artists to an international audience?

Warsaw Gallery Weekend in September is the major event in September. We took part in it last year and presented the work of Magdalena Więcek, a female sculptor. We had her works on paper as well as her sculptures from the ’60s and ‘70s. The weekend is not super well known yet, but I think it has big potential. It’s more about contemporary art since there is so much of it here, but the most important Polish galleries come together and curators are starting to come from all around the world.

Marek Włodarski, Composition with a Brush (1929). Courtesy of Olszewski Gallery.

For a first time visitor to Poland, are there any Modernist landmarks to be sure to visit?

The day trip I recommend from Warsaw is to Podkowa Leśna, a neighborhood that was designed in the 1930s as a garden city. It’s very much the pinnacle of the modern dream: concrete design surrounded by green spaces, created as an ideal place to live. It was directly inspired by the British architect Ebenezer Howard’s concept of a garden city, which he wrote about in 1898. The design is very restricted, from the heights of the building to the garden ratios. It was built very much for the upper-middle-class in a way, for doctors and lawyers, which means it was an easy commute of only 20 kilometers from Warsaw center, with a train that goes right there.