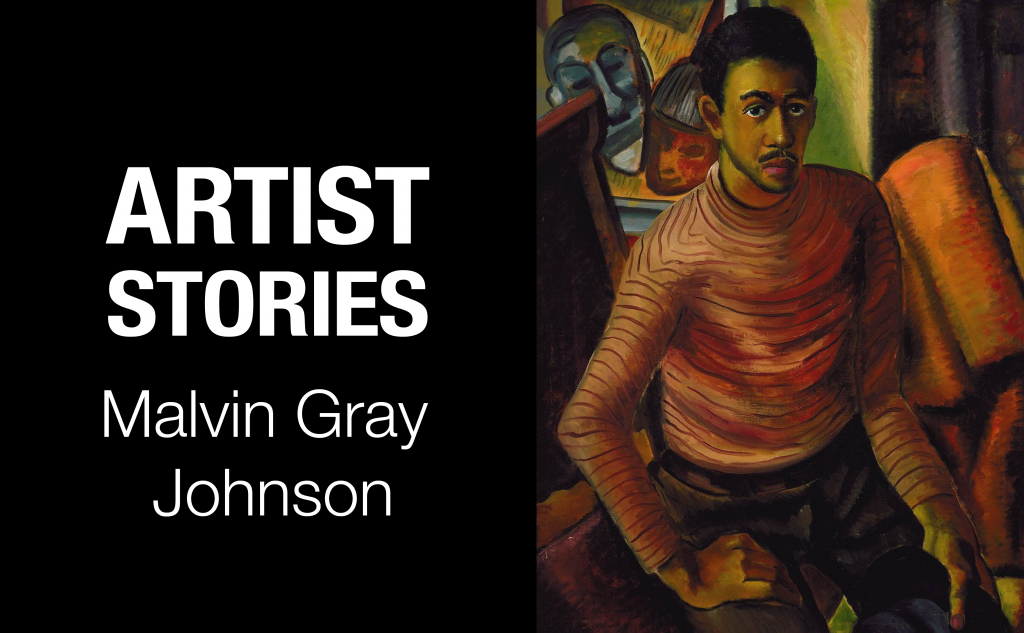

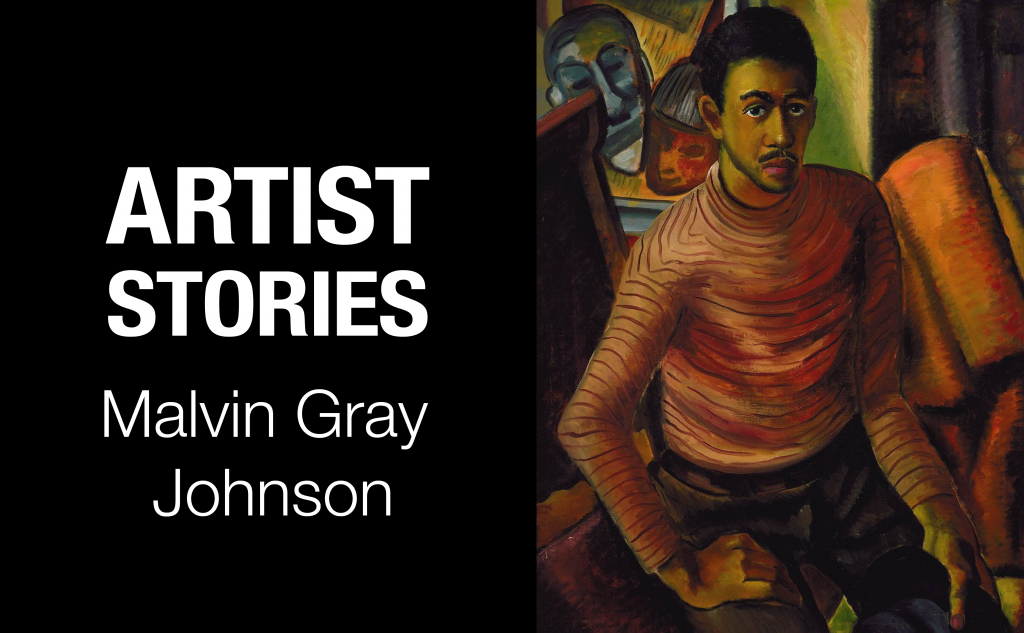

Malvin Gray Johnson’s Striking Portraits of African Americans Made Him One of Most Acclaimed Artists of the Harlem Renaissance. Learn His Artist Story Here

Katie Rothstein

Artist Stories brings to light the careers of artists whose life stories and work may not be part of a traditional art history education. In this series, we’re sharing stories from art history as a first step to building a more diverse canon.

Malvin Gray Johnson‘s entrepreneurial instinct for art was clear from the start. After receiving his first drawing lessons from his sister Maggie as a child, by the age of 11, Johnson had already begun making and selling his own New Year’s calendars in his local North Carolina community. In her biography of the artist, Maggie recalled how her brother would submit his paintings to annual fairs in their hometown of Greensboro. “To his surprise, he won first prize on each of them every year,” she wrote.

Born in 1896, Johnson would move to New York City at the age of 16. There, he studied at the National Academy of Design, working as a janitor and clerk to pay his tuition and taking a brief pause on his education to serve for the US in World War I.

Malvin Gray Johnson, Brothers (1944). Collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of the Harmon Foundation.

Returning to New York in 1923, Johnson resumed his practice, becoming one of the youngest artists associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Primarily based in Harlem, the group of artists, designers, writers, musicians, and thinkers associated with the movement contributed to what many saw as a burst of culture and the rebirth of Black arts in America.

Johnson first garnered national attention for his 1928–29 painting Swing Low, Sweet Chariot. Drawing on themes related to African American spirituals, Johnson wrote that he intended to portray the emotions that enslaved people would have felt at the end of a long day, “calling upon their God for the freedom which they long.” First presented in a group show at the Harmon Foundation in 1929, Swing Low, Sweet Chariot won the organization’s best picture prize that year. At the time, the monthly magazine Art Digest wrote that the painting was “as a significant art world event…worthy of the highest traditions in American painting.” The positive critical reception of the work launched Johnson into public consciousness.

The writer Alain Locke, whose 1925 The New Negro is considered one of the foundational texts of the Harlem Renaissance, was a champion of Johnson’s work. Locke encouraged Johnson and other Harlem Renaissance artists to look to African art for inspiration, and Johnson’s “Negro Masks” from 1932 explicitly draw from a pair of Yoruba and Bwa masks. Alongside his peers Richmond Barthé, Aaron Douglas, Augusta Savage, and Lois Mailou Jones, Johnson’s work was central to the artistic innovations of the period.

Johnson, Negro Soldier (1934). Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Art and Artifacts Division, the New York Public Library.

By the mid-1930s, the Great Depression had descended on the United States. Johnson was one of many artists who participated in the Public Works of Art Project, a New Deal program that employed artists during the Depression. With the money he earned from the program, he was able to travel to rural Virginia where he painted local landscapes and Black American subjects. Despite his previous explorations of African American spirituals and African Modern art, it was the depth of his depictions of contemporary African American life for which he became best remembered. Tragically, Johnson died in 1934 at the age of 38, at the height of his career.

His early death may explain why Johnson’s work is not more well-known or acknowledged, especially as museums and galleries of the period did not often preserve or steward the work of Black artists. Only sixty known works survive today, among them Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, which sold at auction in 2010 for $228,000. The sale perhaps signals that the public is being to recognize Johnson’s significance in the canon of American art.

Still, Johnson’s story contains many “what ifs” as to what his career and legacy might have been with different circumstances and opportunities. His story, and the stories of many other artists whose careers have gone without appropriate recognition, at the very least, are starting to be heard.

Interested in learning more about the artists you love? Sign up for Artist Alerts to receive free customized email updates about all your favorite artists.