Portuguese Painter Maria Helena Vieira da Silva Was Famous in Her Day, Then Forgotten. This Show Puts Her Back in the Spotlight

Katie White

Portuguese artist Maria Helena Vieira da Silva lived about as glamorous a life as an artist could dream of.

Born into an affluent family in Lisbon in 1908, she traveled the world as the daughter of a diplomat, drinking in the influences of avant-garde art movements and styles (she enjoyed the Ballets Russes, for instance). At a young age, she decided to pursue life as a painter and, in 1928, she moved to Paris to study. There, her artistic life blossomed as she developed a distinctive style that playfully embraced Cubism, Geometric Abstraction, and Futurism in a lyrical, freeing synthesis.

What’s more: Unlike many of her female contemporaries, Vieira da Silva met with much success in her lifetime—in fact, considerably more than her husband, artist Árpád Szenes.

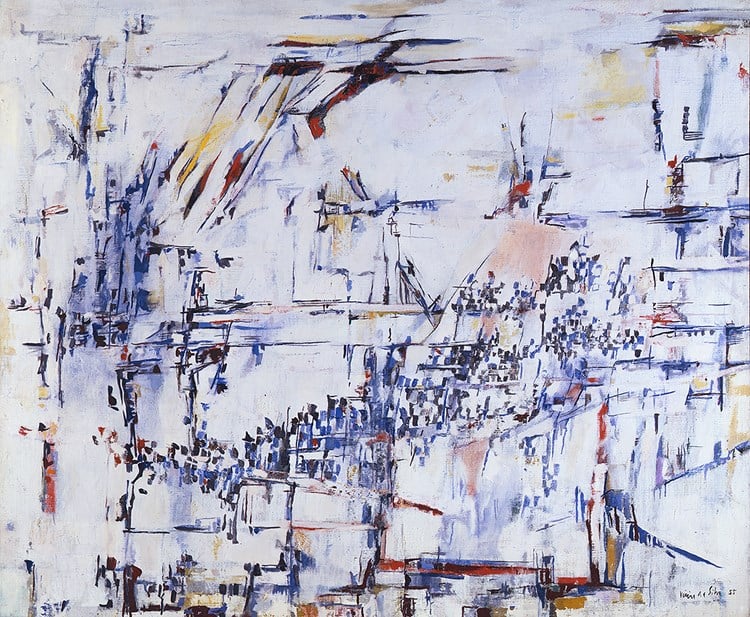

Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, Structure Dynamique (1956). Courtesy of Waddington Custot.

With such a storied existence, it’s something of a surprise that Vieira da Silva isn’t better known today. But that may change soon. A new traveling exhibition, titled simply “Maria Helena Vieira da Silva,” aims to bring her work back into the spotlight. A rare chance to see so many of her paintings at the same time, the exhibition is currently on view at Waddington Custot in London. It has been co-organized by Jeanne Bucher Jaeger Gallery in Paris and Di Donna Galleries in New York, where it will travel next.

Installation view “Maria Helena Vieira da Silva,” 2019. Courtesy of Waddington Custot.

The works on view, mostly from the 1950s and ’60s, are a testament to both Vieira da Silva’s compelling life as well as her impressive sense of experimentation. She lived and worked in New York, Paris, Brazil, as well as her native Portugal, and hints of these cities emerge here and there. Her canvases are sometimes named for specific towns or architectural elements; these are clues that might quietly guide the viewer to look for the pavements and bridges of Lisbon in a work that might, at first glance, have appeared totally abstract.

Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, Sans titre (1955). Courtesy of Waddington Custot.

“Vieira da Silva often painted from memory in her studio, and her work offers a visual expression of the sensory experience of walking city streets,” said the gallery’s Stephane Custot “The Cubist grid, for example, is playfully subverted in her work and its structural framework is interpreted to offer a labyrinthine quality to the surface of her canvases. Sequences of folds, openings, and slippages in format rupture the grid, so that the compositions masterfully combine areas of flatness and depth.”

Installation view “Maria Helena Vieira da Silva,” 2019. Courtesy of Waddington Custot.

Close looking is the key to uncovering the mischief and sense of play that fill her canvases. Seeing so many of her works together at once allows viewers to notice her recurring motifs of ballerinas, harlequins, and card players, who appear and reappear in various guises across the decades. Seen together, and in person, the works in the exhibition offer a window into “a story of the real characters she surrounded herself with in Paris for intellectual conversations and debates over chess and card games,” Custot says—and it is a delightful story at that.

Maria Helena Vieira da Silva. Bibliothèque (1952). Courtesy of Waddington Custot.

“Maria Helena Vieira da Silva” is on view at Waddington Custot in London through February 15, 2020.