‘We All Just Mimicked People!’: Filmmaker Martha Fiennes On Her Famous Family And Creative Beginnings

Artnet Gallery Network

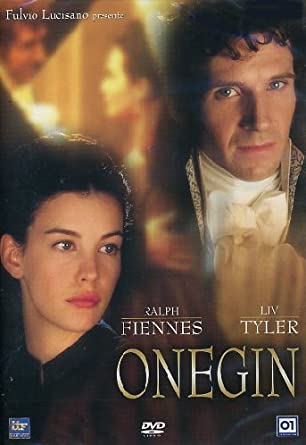

Award-winning filmmaker Martha Fiennes made her breakthroughs with critically acclaimed feature films Onegin (1999), a drama based on the 1883 novel by Alexander Pushkin, and Chromophobia (2005), an ensemble film that starred her brother Ralph Fiennes alongside Penelope Cruz. She is now pioneering a ‘moving image’ artform that combines film and classical aesthetics with technology. Recently Ulvi Kasimov, the founder of .ART, the art world’s digital domain, spoke to Fiennes to learn more about the art world, her creative work, and her famous siblings.

How did you start working in film?

I guess I am an artist whose chosen medium is film. My father was a photographer and my mother a painter and a writer so I can see the consolidation of that influence on me.

I see things quite vividly in my mind. I had an immediate affinity with photography – I would pick up a camera with a keen sense as to how to frame things – but I also knew that the still image wasn’t enough for me. I have a fascination with psychology and what drives human behavior and human processes. A still image, a still painting, or a still object can’t express that sort of evolution. I’m interested in the human condition and the human experience. What better place to explore that than through the world of drama and the behavior of human beings? And then there is another entire dimension – that of sound. Film is a tantalizing medium on so many levels.

Directed by Martha Fiennes, Onegin (1999)

What was your big break in film?

After film school, I came out into a world where music videos and commercials were very prevalent and creative. A music video came along for a band called Furniture with the song Slow Motion Kisses. I was about 22. It had a tiny budget; something like £700 – a joke – so I shot it in a friend’s house. I needed to get myself out there on the map. It was totally cheap-looking but I’m proud of that little video. I remember thinking, I know I can do this.

Then I did my first commercial. Many people view commercials as creatively inferior but it was a heyday of filmic creativity and a very competitive environment. I knew I wanted features in time – but these were important ‘cutting teeth’ processes.

You are now producing what you call ‘autonomous slow-image’ works that combine cinematography and technology with the aesthetics of Renaissance painting. Tell us about this.

I had one of these epiphany moments. Knowing the technology I’ve worked with all my life I thought to myself, what if you aligned certain “potentials” of moving images on a layer and got a computer to select them randomly? And I’ve done enough edits to know that random edits can be really exciting. How incredible to encounter an image on a screen and not know what it’s going to show you next. Can you imagine if you, as a filmmaker, stuffed that piece full of potential images, and yet only it decided what it was going to show you? My God! You could have a piece for five years and not see something in it twice.

As a relative newcomer, what do you make of the art world?

The art world works according to the art world. I’m not “in” the art world – I’m a filmmaker making art. The pioneering element is not only in the work itself, it’s also in the structures of finance; how the art world works, and how the film world works. They’re generally very separate, compartmentalized ‘corridors’ that work according to established principles.

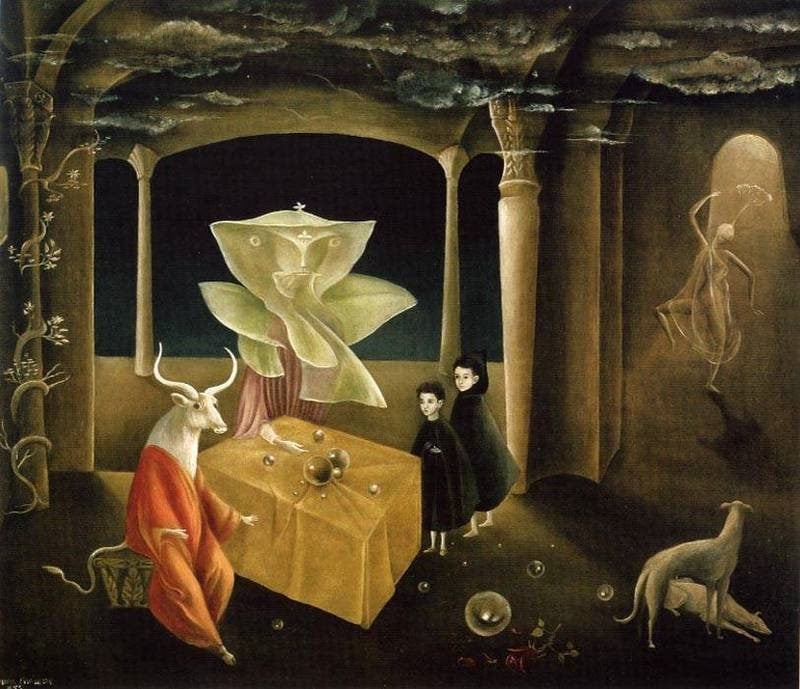

Leonora Carrington, And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur (1953). ©2019, Estate of Leonora Carrington/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York.

Who is your favorite artist at the moment?

The British surrealist Leonora Carrington. I love her work, which is representational rather than abstract or conceptual. Her work pushes boundaries. I like the strange world she’s conjuring up. She’s referred to as a surrealist, but somehow I don’t see her in that bracket. I like her freedom to create these “meta-scapes” of the internal world – of the sub-psyche, the anima, and what Jung called the “dream time”. I think we need this world in our culture. For me, it’s a kind of soul nutrition to look at those paintings. I just smile.

You are part of a very creative family with composer Magnus, film director Sophie and actors Ralph and Joseph among your siblings. Is there any rivalry there?

There is always support and interest but absolutely no rivalry. It would be unthinkable. We are all busy and scattered around the world. You’re not having weekly reunions but you’re speaking to one another at natural intervals. It’s important to remember that we are doing our own thing, entirely independently.

To what do you attribute this familial creativity? Genes or environment?

I think it’s a combination of both. The home environment was very geared to this – not “Sit down, I’ll teach you this” but our mother’s influence was very encouraging of creativity and discipline. She was a volatile person — you weren’t sure what you were going to get – but she was very loving and our father was an extraordinary support mechanism. It was a training ground.

Your brother Ralph Fiennes started his career as a Shakespearean actor before achieving success in films such as The English Patient, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Skyfall and of course your film Onegin. What is he like as a person?

He is a brilliant, generous, extraordinary man. A lot of people say they didn’t know Ralph had such a hilarious sense of humor. Wes Anderson got this other side to Ralph brilliantly in The Grand Budapest Hotel.

And where does the “performance gene” spring from?

We were all brought up imitating. We all just mimicked people. We just loved it! We would call each other and pretend to be someone and see if we could convince them. We were naughty like that. Our maternal grandmother was larger than life and a big player in her local “am-dram”. Perhaps it all stemmed from her!

What keeps you going as a filmmaker and artist?

An urge really. A mad compulsion for it. An innocent fascination. The love of seeing what might happen if x, y, or z could be worked. It starts in the imagination. It’s very much a visceral feeling. It’s potential waiting to be committed and made manifest.

This interview is excerpted from Kasimov’s book The Art of the Possible, a series of interviews that explore the ways Internet technology can remake the art world. Additional interviews from the book will be published here in the coming months.