Max Ackermann Was a Visionary of the German Modernist Movement. Now, a New Exhibition Shines an Overdue Light on His Legacy

Katie White

In art history books, Wassily Kandinsky is often extolled as the artist who led the Modernist art movement toward abstraction. While Kandinsky was no doubt a visionary—and perhaps the artist most able to stir public interest in abstraction—he certainly was not alone in the zeitgeist towards defining a new artistic language.

In those same early years of the 20th century, the German painter Max Ackermann was similarly breaking through the representational image to his own form of energetic abstraction. In fact, Ackermann is credited with creating his first abstract painting as early as 1905, several years before Kandinsky would do the same.

Max Ackermann, Ohne Titel (1948). Courtesy of Galerie Bode.

Though today Ackermann’s name does not ring the same bell of recognition (outside of scholarly circles), “Max Ackermann: The Early Works,” an exhibition now on view at Bode Gallery in Nuremberg is hoping to change that. The revealing—and quite upbeat—show spans the decades of the artist’s career, from 1933 to 1957. In the more than half-century since their creation, Ackermann’s lively works have not lost their pep.

Max Ackermann, Schwebend (1944). Courtesy of Galerie Bode.

A nearly circus-like energy buzzes throughout these works. What first catches the eyes is color; Ackermann’s oil paintings are shockingly bright, with peach backgrounds and lime green tones, that seem unexpectedly jovial, for mid-century German art.

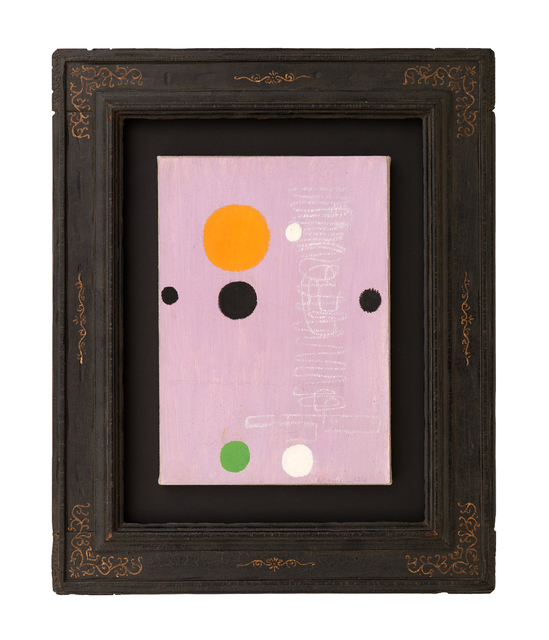

Max Ackermann, Ostern (1955). Courtesy of Galerie Bode.

A sense of play also shines through these compositions. In a work like Ostern (1955) one can see a delicate mobile-like use of line to build a precarious framework off which other graphic elements of squiggles and triangles seem to dangle. The image seems on the verge of motion (this could be an abstracted creature) or collapse. Joan Miró comes to mind, too, though here through the lens of a kaleidoscope.

Max Ackermann, Ohne titel. Courtesy of Galerie Bode.

The exhibition also wonderfully highlights the artist’s drawings from the 1930s and ‘40s. These graphite-on-paper works offer great insight into Ackermann’s graphic sensibility. One finds a desire to play with compositional balance through static and dynamic elements. Ackermann had begun this compositional play with lines, triangles, and circular forms while still a young artist working in his father’s studio. Through the decades, Ackermann continued to develop these motifs as games of push and pull, addition, and removal, to which his drawings were particularly well-suited, and which sometimes get overlooked in his more colorful canvases.

The altogether unexpected exhibition walks a tightrope between vibration and rigidity, solidity and dissolution—but rather than offering any sense of tension, the mood is gleeful with the energy of innumerable possibilities.

“Max Ackermann: The Early Works” is on view at Bode Gallery, Nuremberg, Germany, through August 31, 2020.