How the Mourlot Family Went From Making Wallpaper to Running a New York Gallery and a Fine-Art Print House

Artnet Gallery Network

“It’s amazing how many people don’t understand what a print is,” says Eric Mourlot, the fifth-generation owner of Galerie Mourlot and its printing arm, Mourlot Editions. “A lot of people think it’s simply just a reproduction, but it’s not—it can be so many different things. It’s a medium just like anything else.”

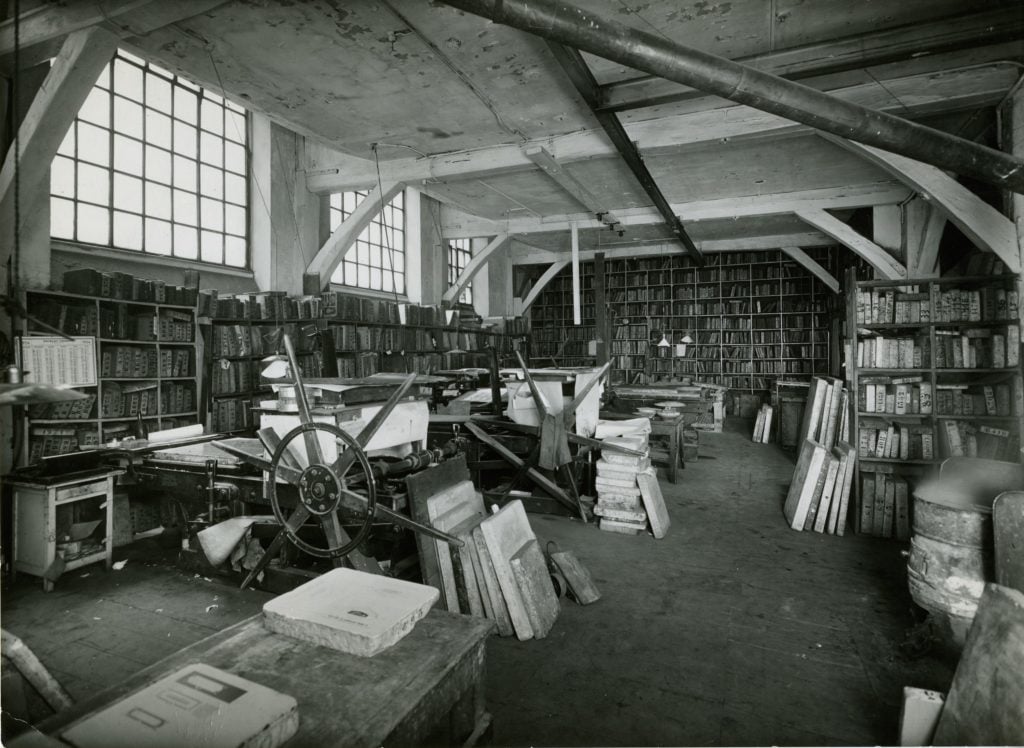

The name Mourlot has been synonymous with printing for over a century and a half. Eric’s great-grandfather, Francois Mourlot, founded the Atelier Mourlot in Paris in 1852, producing wallpaper and commercial labels. In 1914, Francois’s son Jules expanded the business’s operations to include illustrated books and posters. By the time Fernand Mourlot (Eric’s grandfather) took over in the 1920s, Atelier Mourlot had become one of the biggest and best-known print shops in the world, specializing in lithography. They worked with some of the most important artists of the day—Picasso, Matisse, Miró, and Chagall, to name a few—to produce original prints, and made exhibition posters for France’s biggest institutions.

Atelier Mourlot Paris, c. 1950. Courtesy Galerie Mourlot.

Jacques Mourlot (Eric’s father) took over the studio in the mid-‘60s and oversaw the opening of a new branch on Bank Street in New York. There, the company continued its run of high-profile collaborations, working with artists such as Robert Rauschenberg, Francis Bacon, Roy Lichtenstein, Alexander Calder, Ellsworth Kelly, Alex Katz, and Claes Oldenburg to make masterpiece lithographic prints.

Finally, in 1999, Atelier Mourlot was forced to close. In an age when cheaper offset and digital processes had become the industry norm, the costs of running of a traditional print shop had simply become unsustainable. However, the Mourlot name didn’t disappear from the art world. Far from it, in fact.

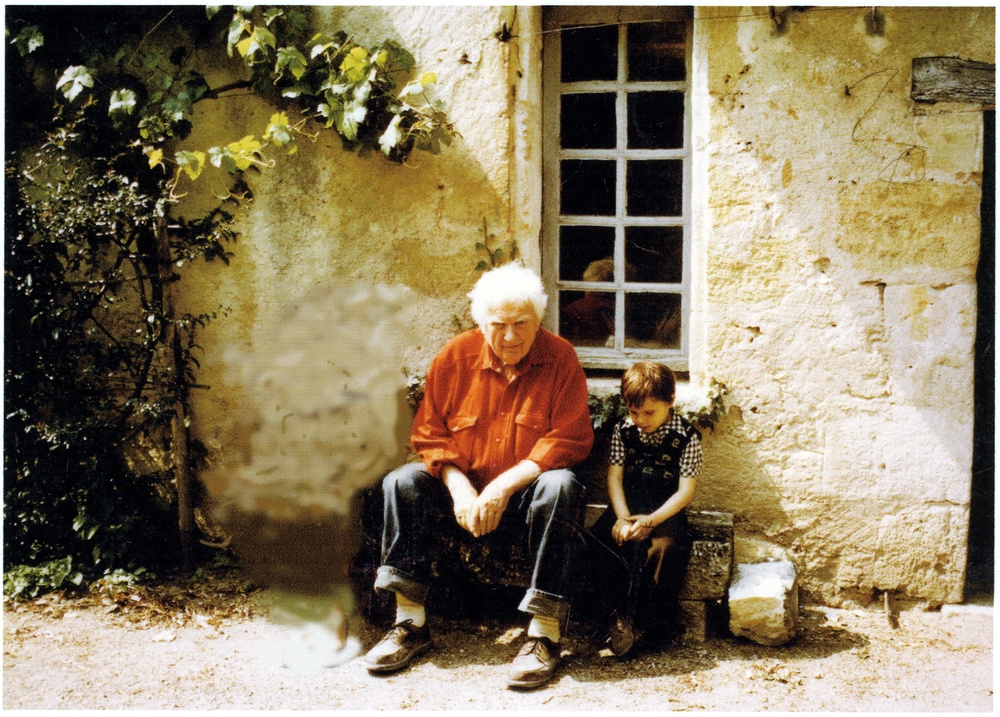

Henri Matisse and Fernand Mourlot at Atelier Mourlot Paris, c. 1948. Courtesy of Galerie Mourlot.

Opting to become a dealer rather than take over the family business, Eric Mourlot opened his first gallery in Boston in the early 1990s, selling modern masters and contemporary up-and-comers. He moved his gallery to New York in 2005, setting up shop on the Upper East Side. Galerie Mourlot occupies the same space today, putting on contemporary shows, working with artists, and managing the remnants of the printing business (an incredible stock of rare prints, books, and various archival materials).

For Mr. Mourlot, it’s a balancing act between working to carve out the gallery’s place in the contemporary art landscape while being also being a steward to his family’s rich history. It turns out he didn’t need to look far for a solution.

“I decided to go back to the essence of what my grandfather was doing,” he says.

In the 1920s, Fernand Mourlot convinced the museums in France to advertise their shows through posters and prints, and as result, attendance started rising. “The idea was to make quality, original art accessible to the everyday man in the street,” Eric says. “That’s what I’m trying to do now, too.”

Alexander Calder and Eric Mourlot. Courtesy of Galerie Mourlot.

With Mourlot Editions, the gallery is doubling down on the reputation of the family name and working again to publish collectible, top-quality prints by contemporary artists at an affordable price point—usually ranging from a couple hundred dollars to a couple thousand. They’re working with a variety of different artists, from neo-pop artists like Kristin Simmons and M. Schorr to photographers like Celia Rogge and Eva Petric. They’re also investing heavily in social media—an updated version, Mourlot notes, of the kind of press his grandfather helped pioneer in the arts nearly a century ago.

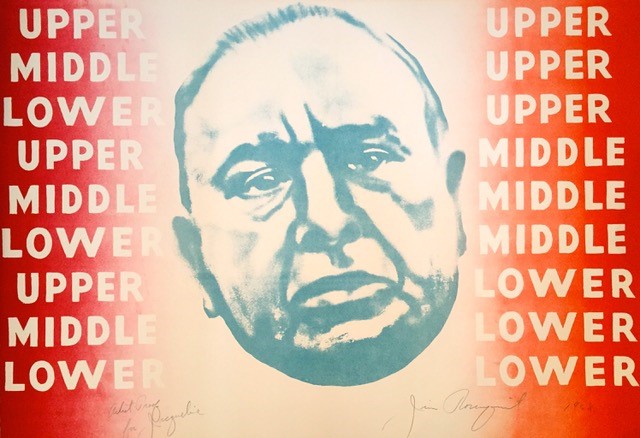

“My grandfather worked with Picasso, Matisse, Chagall, Miro; my father worked with Lichtenstein, Ellsworth Kelly, Rosenquist, and we’re still offering all these works, but on top of it, we’re now bringing in a new batch of artists that we feel art relevant and important,” he says.

Below, Mourlot details the history of his family’s famous printing house and the gallery’s new direction by highlighting three posters—one for each of the last three generations of Mourlot men.

Henri Matisse, Marquise de Pompadour (1951). Courtesy of Galerie Mourlot.

“As one of the very few proofs printed on Arches paper that were reserved for the artist, this extremely rare lithographic poster was created for the Annual Ball of the School of Decorative Arts in November 1951 by Henri Matisse. Having composed this magnificent design with paper cutouts, the event was to benefit the alumni of the school and attended by many cultural luminaries of the time, under the patronage of the President of France and the Minister of Culture. Matisse’s original edition with Mourlot for this print was 1,500 on regular paper and about 20 on Arches paper, the subject the Marquise de Pompadour, was also known as the mistress of King Louis XV and was thought to have prompted the creation of the school.”

James Rosenquist, See Saw, Class System. Courtesy of Galerie Mourlot.

“This 1968 original color lithograph on Arches paper, signed in pencil was published by Richard Feigen Graphics. Rosenquist created this lithograph when the United States was on the cusp of radical social changes in the late 1960s. The composition is dominated by the portrait of Chicago Mayor, Richard J. Daley, framed by a word puzzle constructed from variations of the words upper, middle, and lower as a reference to class systems. Daley’s scowl and the image’s wordplay, suggest the catalysts for this work were likely the riots sparked by protests during the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, as well as race relations and the country’s war on poverty.”

Kristin Simmons, High Heels, High Hopes (2017). Courtesy of Galerie Mourlot.

“This original Silkscreen by New York artist and Columbia University graduate Kristin Simmons is reflective of Mourlot Editions’s desire to give a platform to young and relevant artists. This piece memorializes the ‘Madison Avenue Barbie’ the artist was gifted as a child, which upon later reflection allowed her to take a unique view on the renewed social pressures that women face in the 21st century. Simmons highlights the problematic nature of the toy itself—the plastic limbs of the doll, coupled with her static pose and provocative corset—are a reminder of women on the upper east side that are expected to fulfill a certain ideal of the perfect companion. To this, the artist has inserted a Russian passport, a bag from Tiffany’s, and a presidential seal in an ode to our current state of affairs.”