At 167 Years Old, the Print Shop and Gallery Mourlot Editions Isn’t Afraid to Reinvent Itself

Katie White

Despite his family business being over a century-and-a-half old, Eric Mourlot, the head of New York’s Mourlot Editions and great-grandson of the company’s founder, believes you can certainly teach an old gallery new tricks. The veteran print shop and gallery, which first opened as Atelier Mourlot in Paris in 1852, has long epitomized the gold standard in fine art printing. With roots in wallpaper and commercial printing, the Atelier eventually expanded to include illustrated books and posters, and, by the early 20th century, gained acclaim for its collaborations with modern masters including Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Marc Chagall, and Joan Miró.

But for Eric Mourlot, who runs the company’s current Upper East Side location, it is essential not to get caught up in the trappings of convention. With a roster of contemporary artists including Eva Petrič, Kristin Simmons, and Stephane Kossmann, Mourlot has worked to carve out success in unexpected places. We caught up with Mourlot, who offered his thoughts on the death of the mid-tier gallery system, the possibility for true change in art market, and more.

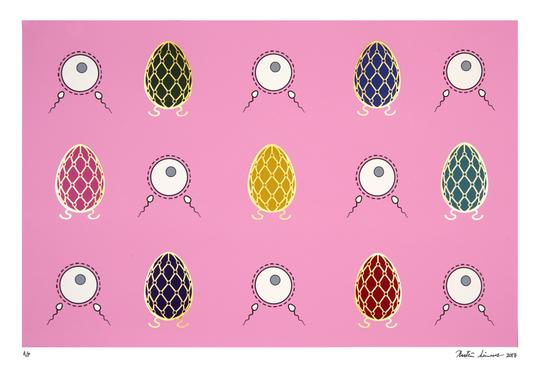

Eva Petrič, Birdy (2017). Courtesy Mourlot Editions.

Mourlot Editions is a multi-generational business. Practically speaking, you’ve been working in this field your entire life. From your perspective, can you describe what today’s art market looks like? What are its struggles and pitfalls?

The art market has been contracting since 2007, at the same time that auction records have been breaking. Galleries in the middle are consolidating or dying. One conclusion to this situation, which is not necessarily an actual solution, is that artists need to gain a foothold with the top galleries. I read somewhere that the average revenue for 55 percent of galleries is about $200,000 a year. With $100,000 going to the artists for commission, you’re left with $100,000 to run your gallery. Good luck with that. You can’t make a dent with that. With this in mind, artists would need to attract enough attention to get into one of the top galleries in order to survive, which is also very unlikely, if not impossible. The control of the gallery world as I see it is shared between 15 to 20 galleries at most, and the ways they pick their artists can seem random and arbitrary.

That’s a harrowing landscape for any gallery or artist. How have you met these challenges?

I have been rereading my grandpa Fernand Mourlot’s autobiography. He writes about why he began collaborating with museums to make exhibition posters. The posters were a way for artists to reach the man on the street. Many people didn’t know what a Picasso looked like until they saw a poster in a gallery window or on the walls of Paris. Nowadays, attendance at museums has never been higher, but this doesn’t equate to buyers. I kept this idea of access with me when I opened a gallery space in Boston in 1991, and then when we moved here to New York. I chose to see publishing and printing as a way to democratize. I am not the first person to have had this thought, nor do I pretend to be, but I do think we’ve been able to do pretty well compared to the “regular” art market because of this thinking. We’re using technology to its best by partnering with different platforms to reach a new audience. It’s harder to go from the bottom to the top of the gallery pyramid than to offer a variety of curated choices to a larger group of people.

What kind of artists are you working with? What other principles do you bring to your business model?

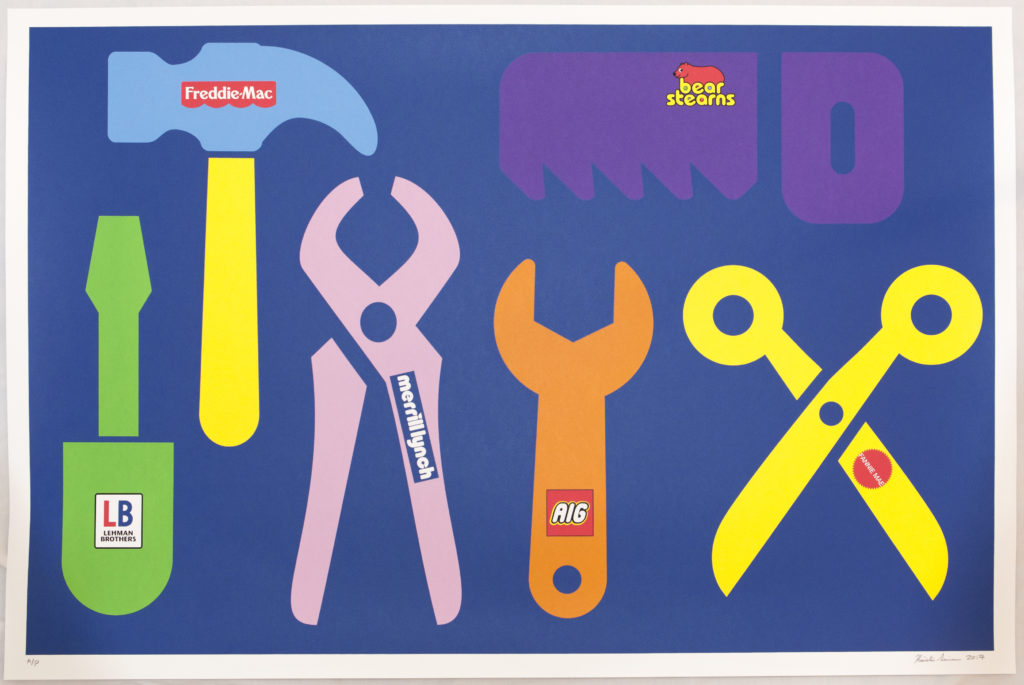

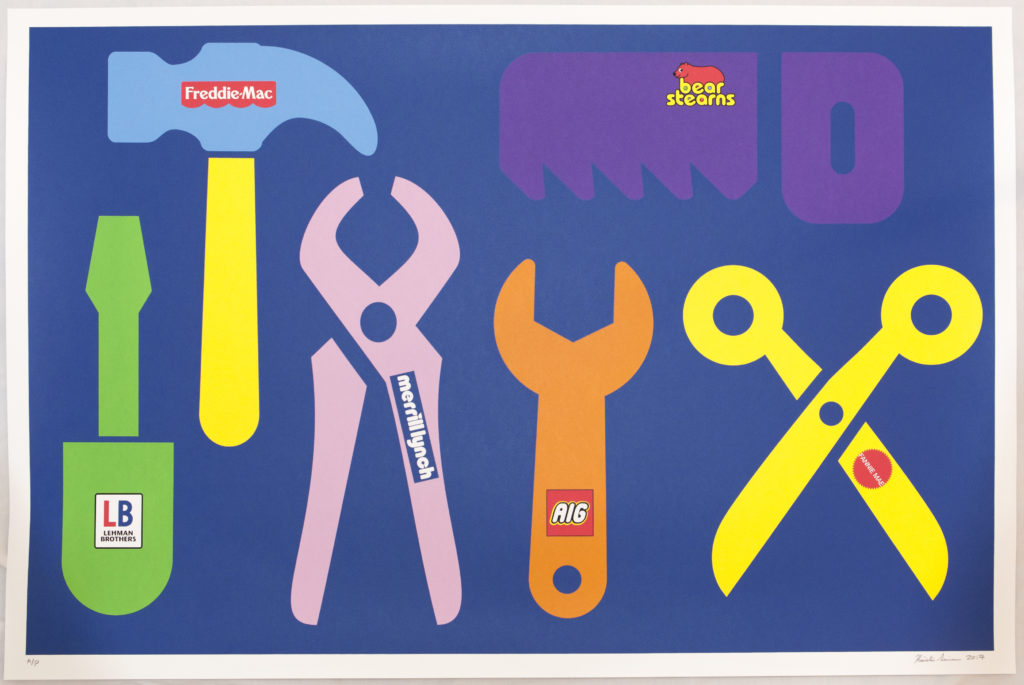

Just as my grandfather worked with Matisse, Picasso, and Chagall, and my father with James Rosenquist, Ellsworth Kelly, and Alex Katz, I am working with new generation of artists who explore a variety of styles. Among these is Eva Petrič, who works in performance, installation, and photography; Kristin Simmons, who has a neo-Pop aesthetic; Mitchell Schorr, who is more of a street artist; and Robert Salmieri, who is a serialist. Our gallery aims to be democratic in its representation as well. Our artists range in age from 29 to 79 years old. We have as many female artists as male artists. We’re committed to equal pay. Our most expensive artist a woman, Kristin Simmons. One of the keys to our success is that we look to perhaps uncommon areas for exhibitions. Petrič has an installation at the Cathedral St. John the Divine uptown right now. Simmons just been named the first artist-in-residence by the United Nations’ SDG5 Global Alliance, whose mission is the empowerment of women and girls.

Kristin Simmons, Eggspensive (Pink) (2017). Courtesy Mourlot Editions.

What is technology’s role?

Our philosophy is to embrace technology without becoming a slave to it. We’re trying to use technology as a platform for our artists that they wouldn’t be able to use on their own. But we remain committed to old-fashioned printing and publishing. We send our artists to print shops, like the Lower East Side Printshop. I still have presses in New Jersey and I keep threatening to reopen a studio. At the end of the day, I’m a printer and publisher. The gallery system was no longer working and we needed to evolve. Our ambition now is to offer our artists a real audience that may not be millionaires and billionaires, but who truly enjoy collecting.

It seems like you’re describing a specific audience. Can you describe the collectors you’re trying to connect with?

As prices rise astronomically, people get turned off by collecting and prefer to enjoy it at the museum and purchase a poster or something more decorative. I think we’re offering a good alternative for that person. Since the old days with editions of Picasso and Miró, doctors, lawyers, and architects all wanted an artwork that was original, signed, and very intimate in a way, but not at the price of unique works. We’re working on that premise, in small editions of 10, 25, or 50, which allow price points to be much more accessible.

Mitchell Schorr, Ice Cream Truck (2017). Courtesy Mourlot Editions.

Do you think that Mourlot’s printing heritage has made it more adaptable than a typical gallery to new models?

I think it was a combination of factors. If you’re in front of a psychopathic system, as I would consider the current gallery system to be, the best solution is not to engage. There is no point in fighting it. Instead, build your own thing that is positive, that is looking towards the future. Circumstance and naïveté also played their parts. When I started the Boston gallery in 1991, I already had the passion. I wanted to do something valuable. Selling works by dead artists is not necessarily valuable. You can be a steward to history, which we are, honoring our history with lithographs by the masters. But the excitement comes from taking a contemporary artist who has talent and promise and being able to create an environment that allows that person to make a living and to do what they have to do artistically. I was naive in that I thought, “Build it and they will come.” It wasn’t as easy as I thought and there were missteps. In 2008, I opened a gallery in Los Angeles which was ultimately a failure, for instance. It was through trial and error, and also having a more egalitarian approach to art, that we came to technology and internet engagement as the platforms where we ultimately built our audience.

What factors do you believe have driven the success of your online sales?

In my experience, the key to online success is the ability to provide both enough variety and context for collectors. Mourlot Editions has an association with printing’s history dating back to 1852. In some ways it is this sense of tradition that gives us credibility with new collectors. In the first few months of turning to these online outlets, we were able to make significant sales. This was both comforting and eye-opening, as I saw we were able to sell more than modern masters. And no matter what the model, in the end, the system has to be win-win. Artists have to be happy, collectors have to be happy. If creating a new model is just an avenue to re-enter the traditional market in a different way, there is no true change. Keep the good from the past, the small editions, the quality, and embrace the future.