‘History is a Spiral’: Olga Sviblova, Curator of Moscow’s Multimedia Art Museum, On Art’s Role In Times of Tumult

Artnet Gallery Network

Olga Sviblova has led a pioneering, decades-long career in the Russian art world. In 1996, she founded and then served as director of Moscow’s Multimedia Art Museum. Her interest in contemporary art’s relationship to communication and technology has since informed her creation of the Moscow International Photobiennale and informed her curation of the Russian pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2007 and 2009. Sviblova recently sat down with Ulvi Kasimov, the founder of .ART, to talk about art’s essential role in a tumultuous world.

You founded what is now the Multimedia Art Museum in 1996 and, more recently, the Moscow International Photobiennale. You’ve also curated the Russian pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2007 and 2009. What motivates you in your work?

Passion, love and the future. I’m a lucky person because I’m working in art. I was just 19 when I married the great Russian poet Alexei Parshchikov. He wrote totally unofficial literature. I think I have an innate ability to detect talent and I have a natural instinct to share my discoveries.

One of your breakthrough shows, the Festival of Soviet Underground Art, showcased emerging artists in Finland in the late 1980s. Why did you do that?

It was everything: art, photography, cinema, poetry, performance, music. They were young people who were my friends. I trusted then, as I do now, in their genius.

What is art’s relationship to history?

History is the biggest garbage mountain but we can find, with our light, what is important for us. Mostly we are looking for history because we want to construct the model of our future. Art is for the future. It’s the best way for human civilization to communicate with our own history.

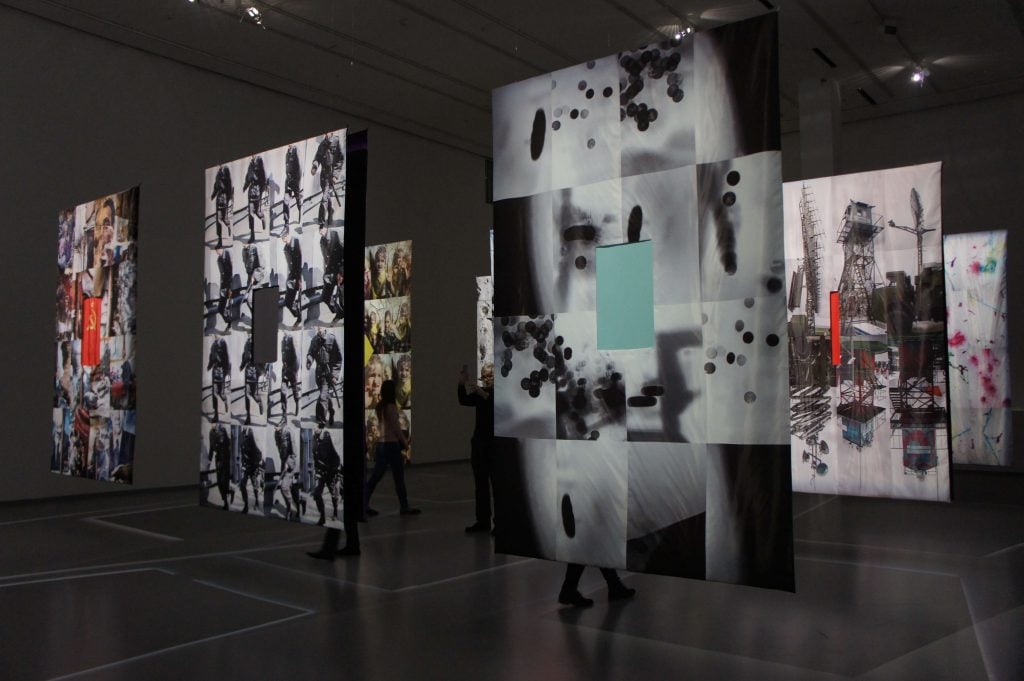

Installation view of “Empire of Dreams.” Courtesy of Moscow’s Multimedia Art Museum.

You explored the themes of connectivity when you curated the Russian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2007. Tell us about that.

I put up the biggest screen possible and installed a group work entitled Click I Hope. For the first time, the Venice Biennale was connected with the entire world. Click I Hope was very simple: you saw a clean screen and the expression I hope in 50 languages. People were invited to click on their language version of the expression I hope and a counter displayed the number of people actively involved in the project. You could touch a screen there but you didn’t need to be in Venice; you could communicate with the project from your computer anywhere in the world. The text in different languages changed size according to the number of clicks on each. English was the leader but the Spanish started to creep up, then it was Russian, then Chinese…

What attracted you to this work?

Most multi-media participation computer games are based around trapping and killing but here you had “hope”. It also reflected activity around the world. For example, the Georgian language phrase started to get bigger just after the Russian-Georgia war.

How is the process of pulling together a major exhibition today different from 30 years ago?

It functions exactly as it did in the 1980s when there was the first explosion in the visual art market. The mechanism is just the same, it’s just that it’s more global. Globalization and economic change also apply to the art world. We now have the “mega-gallery” such as New York’s Gagosian and the “mega-museum”. It’s still centralized and pyramidal though.

What difference will technology make to the experience and appreciation of art?

Art needs to be where communication happens. So if communication is happening on the internet then art needs to happen there too. Art needs to deal with what can be found in situ. Duchamp used ready-made pieces found in real life. What is the difference between finding garbage for an Ilya and Emilia Kabakov installation in reality or finding elements of garbage on the internet? There’s no difference.

Is it going to get easier for the artist to make a living in the digital age, particularly with a greater audience reach?

There are hundreds of thousands of people with diplomas in art. We have more artists, more proposals and it’s extremely difficult for an artist to leave their day job. The world is full of the tragic life of the artist. It doesn’t give you security for tomorrow. Digitization of art will be similar to the luxury market – they have a bigger audience but at the same time, they have lost their exclusivity.

Working in Russia, you’ve put on some very charged artworks, which might surprise some people. Do you feel free to do what you want to do curatorially in Russia?

No. If I look at my life in the 1980s and 1990s there was great freedom in Russia. Everybody wanted to move from Russia at that time—was nothing to eat and nothing around but we were creating something for the future. My idea was to create the Moscow House of Photography for the future. However, I say I’m not free because I’m honest. Ask my colleagues in France if they are free. If they tell you they are free they are not being honest. Nobody is free.

Tell us about the Multimedia Art Museum in Moscow.

We are one of the most visited museums; 75 percent of our audience is between 18 and 35 so it’s really young people. I’m really proud of our brilliant auditorium. There are great pieces of art, great books, and great cinema.

Do you have freedom as a director there?

Throughout twenty-one years at my museum, nobody has told me what I’m obliged or need to do. It’s my decision. Of course in Russia now, politically, we are more careful. Who knew that at the end of the 20th-century conflict between the different religions and nations would arrive so strongly and stupidly? If you don’t want to provoke somebody stupid it’s better not to provoke. History is a spiral: there are easier moments and more complicated moments. If you want to survive, the most important material is human material.

As a filmmaker are you interested in exploring virtual reality formats?

VR is totally new; it’s a totally different logic. It’s totally another way to relate to the hero, to construct a story. I’m always looking for new conceptual models to create a piece of art.

What big projects do you have for the future?

I would like to organize an international conference entitled Revolution Dot Art because I have a feeling it’s a revolution. I think if a lot of intelligent people from different fields are brought together – they may never provide the answers but they will pose more questions. I think it will be interesting. It’s intrigued me. I’m in love with this idea. It will be in Moscow most probably.

Do you feel positive about the future of art?

In 2012 I organized two exhibitions by the photographer Sergey Shestakov, both featuring old ladies in abandoned cities. The images really fascinated me. In Chernobyl, 25 Years Later Sergey photographed an old woman living alone with her cats; a normal life conserved in a field of destruction. And in Journey Into The Future. Stop #2. Gudym, there was a photograph of the inside of an old woman’s house. On the wall was a note, daubed in red pencil, with the words Everything will be fine, even if it turns out to be otherwise. In other words we have reason to be optimistic, and believe in good, through the hardest times. This is something I’ve remembered for many years and I think it’s a great expression.

Why do we need art?

Art is communication. When we read a book or go to the cinema we are communicating with ourselves through art. Our interpretation depends on what we have inside. It’s a mirror. But why do we need this mirror? It’s not just knowledge; this piece of furniture was made in that century for example. Something profound happens in ourselves. This is the reason we need art.

This interview is excerpted from Kasimov’s book The Art of the Possible, a series of interviews that explore the ways Internet technology can remake the art world. Additional interviews from the book will be published here in the coming months.