‘You’re Only as Good as Your Last Couple of Shows’: On the 25th Anniversary of His Gallery, Peter Blake Reflects on the Ups and Downs of Art Dealing

Katie White

Laguna Beach dealer Peter Blake has chutzpah. Twenty-five years ago, he abruptly left the restaurant industry after walking by a clean white space for rent. Two days later, he’d signed a lease and was well on the way to opening his eponymous gallery, a decision he made simply because he “felt like it.”

Focusing on what is today known as West Coast Minimalism and Light & Space, Blake started off wanting to “show the great work of California artists,” giving exhibitions to the likes of Larry Bell and Mary Corse long before they were familiar names.

A quarter of a century later, Blake is regarded as the longest-running dealer of California Light & Space around. In an industry where galleries come and go, the quick-talking, energetic dealer has managed to endure the ups and downs of a volatile field. How? “I’d like to think it’s because I’m a tough motherfucker and I’ve got what it takes to be in this business,” Blake ventured. We caught up with the gallerist to talk about staying power, losing artists, and the highs and lows of his singular career.

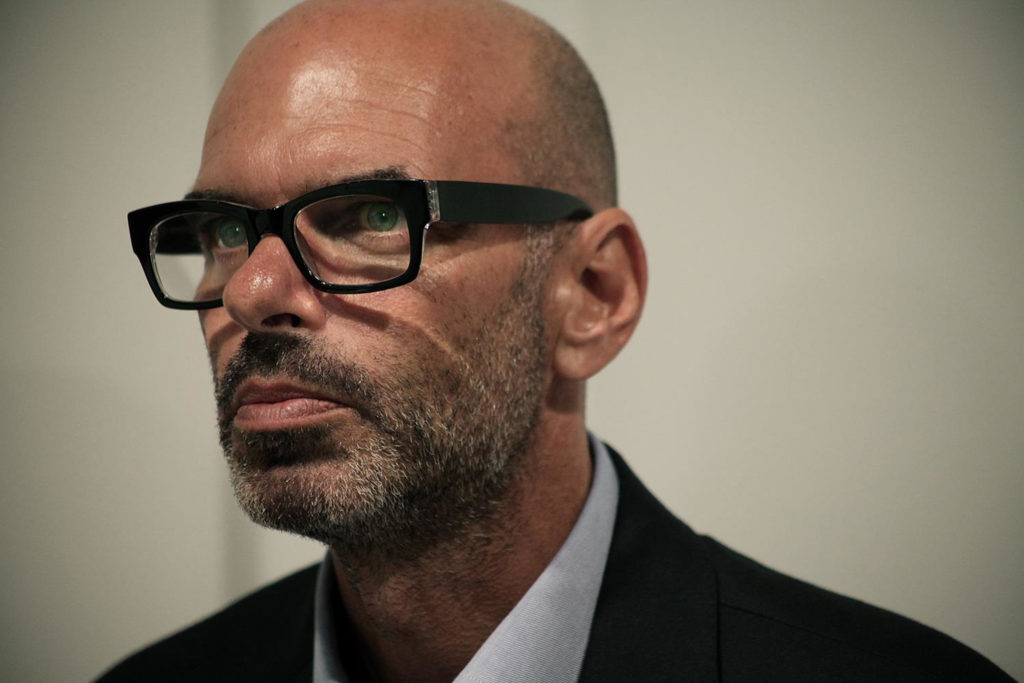

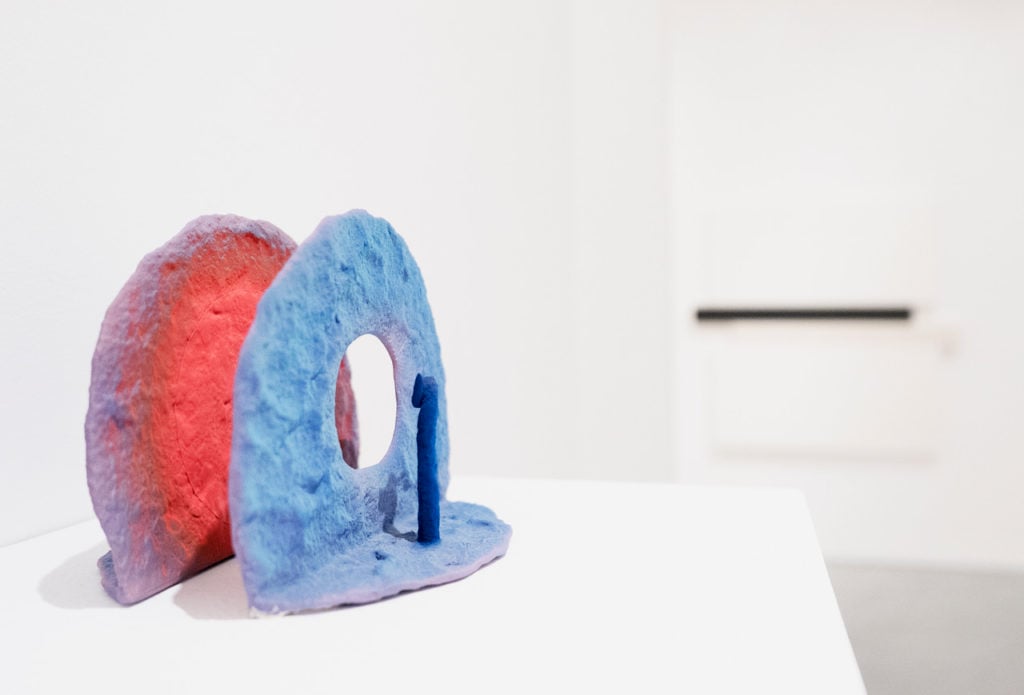

Installation view of “25 Years” at Peter Blake Gallery, 2019. Courtesy of Peter Blake Gallery,

Congratulations on your gallery’s 25th anniversary. That’s no easy feat. Looking back to the beginning, how did you decide you wanted to start showing Light & Space artists and West Coast hard-edge painters?

Actually, what led the gallery at the beginning was a geographic emphasis more than a type of art. I wanted to have a gallery that celebrated the artists of Laguna Beach so I went out and found the best artists in the area. A couple of years later, I organized an exhibition for an artist that was represented by L.A. Louver. That prompted a great relationship and even mentorship with Peter Goulds and Kimberly Davis, two of the gallery directors there, and myself. As time went by, I wanted to have the best artists from Los Angeles, so it became more of a regional gallery, then the whole state. For about 15 years, I exclusively showed California artists. Then I decided to start to show some New York and European Minimalists, which opened up the world. But I began as a California gallery and that’s what led to showing Light & Space and hard-edge work.

Installation view of “25 Years” at Peter Blake Gallery, 2019. Courtesy of Peter Blake Gallery,

You were working as a restaurateur when you suddenly decided to lease a space and open your gallery. Just this year, you decided to run for city council and won. This speaks to a real conviction of confidence, but also a sense of spontaneity. How do you think these qualities have informed your career?

The restaurant industry I came up in is nothing like the hospitality industry of today, which is in and of itself a career that people take very seriously. The work ethic is different because people are trying to move up the ladder and get better and better jobs. Working with people who didn’t see that restaurant necessarily as a long term career really helped me learn how to manage artists, because as we all know art is a very difficult career to actually make a living doing. When I ran for council, I realized a lot of those skills were helpful to me from a political perspective. In the end, that spontaneity is a lot of what’s kept my gallery open. I opened a gallery out of nowhere because I wanted to. I was just naive enough and had just enough ambition and courage to do it. Same with the political thing—I woke up one morning and felt I’d had enough and got into it and wound up winning. I’ve been a very strong council member since I won, meaning a lot of people can’t stand me.

How has the perception of West Coast art from the 1960s to today changed over your career?

There’s been a tremendous change from the days when no one was interested or really respected these artists coming out of LA. Pacific Standard Time, the Getty initiative, totally opened up the world’s eyes to Light & Space and California Minimalism. Then in 2010, David Zwirner’s show “Primary Atmospheres” in New York was a kind of breaking point that signaled that New York had accepted California Light & Space. New York had accepted it, and therefore the world accepted it. Big galleries went on to pick up some of these artists; Larry Bell was picked up by Hauser & Wirth, Mary Corse by Lehmann Maupin. I remember art fairs where people would walk in and look around and say, “what is this?” and I would explain to them what I was showing. In the last few years, people walk in and know Larry Bell, Mary Corse, Craig Kauffman.

Some of the mega-galleries are taking these California artists, and unlike me, just making them international artists who happen to be working in Minimalism, with a capital M, as opposed to California Light and Space or hard-edge. They’re being viewed as part of the Minimalist movement.

Installation view of “25 Years” at Peter Blake Gallery, 2019. Courtesy of Peter Blake Gallery,

How would you characterize the West Coast Minimalists as opposed to the New York school of Donald Judd, Robert Smithson, and the like?

The LA minimalists and Light & Space artists are laid back. There is a sensual nature to their work. It’s more about beauty and references the atmospheres of California: the smog, the mist, the ocean. A lot of these artists were car buffs, they were surfers, they were working with materials in their art that they worked with at their jobs and in their lives.

The New York Minimalists are more scholarly and academic. They were writers and able to insert their work into the context of academia. They could take nothing and turn it into something intellectual. The Californians I don’t think ever felt the need to contextualize their work, but let it speak on its own, as beautiful objects that capture the light of the environment.

Many of the artists you’ve shown have become very established. Have all of the significant West Coast artists of this generation reached a kind of stratospheric level of recognition, or are there others that remain obscure?

Certainly there are artists on the cusp right now. Peter Alexander is about to go big like Mary [Corse] and Larry [Bell]. A next generation of hard-edge painters is rising too. Scot Heywood is painting in that same lineage as John McLaughlin. Lita Albuquerque is a really remarkable multidisciplinary artist who operates not only within the Light & Space movement but also in performance, installations, video, and photography. We still have plenty of California artists from that generation who are waiting for this widespread recognition.

Installation view of “25 Years” at Peter Blake Gallery, 2019. Courtesy of Peter Blake Gallery.

Are there any moments that really stick out to you in your career as successes or failures?

Sometimes the highs and lows are one and the same. Watching some of our artists get picked up by larger galleries and seeing prices skyrocket, on one hand you feel this incredible pride. You started showing these artists before anyone else did. But then you lose them. It’s a real dichotomy.

With collectors, they’re thankful: “How many times has this dealer brought me something that he said I should buy, and look at what’s happened to it!” That’s measured with this low of, “I can’t get you that work anymore.” The artist gets so big that I have no access to their work, which is always distressing.

It’s not an easy business.

We’ve had this ongoing joke that started around 2008 and the Great Recession. When we would make a sale, I would look at my wife and my staff and say, “Well, looks like we all have a place to work for another month!” You’re only as good as your last couple of shows. It’s rare that galleries are supported with huge amounts of money. While today many galleries are owned and operated by people who have inherited a lot of money or whose spouses have a lot of money, those galleries usually last about two years.

Even the richest people who open galleries get the call from the accountant that tells them, “Look, you’re losing a lot of money. You could take this same amount, write a check to LACMA, fly to the Hamptons, go to Aspen for ArtCrush, Basel in Switzerland, and throw parties in Miami, and you still wouldn’t lose this kind of money. So why would you want to endure this job?” Not many people want to roll walls and mop floors and pour people drinks and deal with all the BS that you deal with as an art dealer.

So then, why do you?

Freedom. It is one of the luxuries of the art world. I speak for myself—I do whatever I want, whenever I want. I don’t have anyone telling me what I can and can’t do. So if I want to show this today, I show it. If I wake up tomorrow and decide I want my gallery to focus on something else, I can do that.

Most people in this world will never see a day or a month of that kind of freedom. It comes with a severe price, but if you’re willing to pay it, the art world is a great place to be.

Any memorable experiences as a dealer?

Because I show Minimalism, there are always these “what the fuck” people. That’s a most favorite phrase. Our gallery has an all-glass facade, so it’s pretty easy to see from the outside that there’s nothing you’d like to see. The incredible comments that arise as people try to determine “is this art?” are amazing.

And I’d say the selfies are just the most horrendous part of going to art fairs now. People are so compelled to put themselves inside of an art work and make all of these faces and hand gestures. It’s ridiculous, the damage occurring as a result of selfie generation. We had our first major damage, the first insurance claim we ever made for over $250,000 because some father and son were playing hide and seek behind an artwork and knocked something over.

We’ve had many near misses and close-calls as result of selfies.

Installation view of “25 Years” at Peter Blake Gallery, 2019. Courtesy of Peter Blake Gallery.

What’s on tap for the next 25 years?

A couple years ago, during my second midlife crisis, one that couldn’t be solved with a red car and a divorce, I decided to introduce design works into the gallery program. I had always loved architecture and design just as much as art.

A few years ago, we had this show called “Tendency of the Moment,” a survey from Bauhaus to about the early 1970s, based on the collection I built with my wife. It opened up a lot of dialogue that led to a better understanding of how those two worlds were headed into each other. Now, we proudly show design. We are getting ready to do Salon Fine Art in November and Design Miami in December.

Lately, my gallery no longer feels like the white box it was for 25 years. Now, it’s become this kind of experimental space where we could have a pop-up dinner, music, tastings, poetry, show secondary market work, show design. I don’t feel that compelled to be locked up in the white cube anymore. Mind you, I am a total white-cube enthusiast and if I could return to the old days, I would. But we’ve left that place.