Pioneering British Pop Artist Peter Phillips on Still Working at 79, Lichtenstein’s Generosity, and Why He Doesn’t Think Much About Legacy

Taylor Dafoe

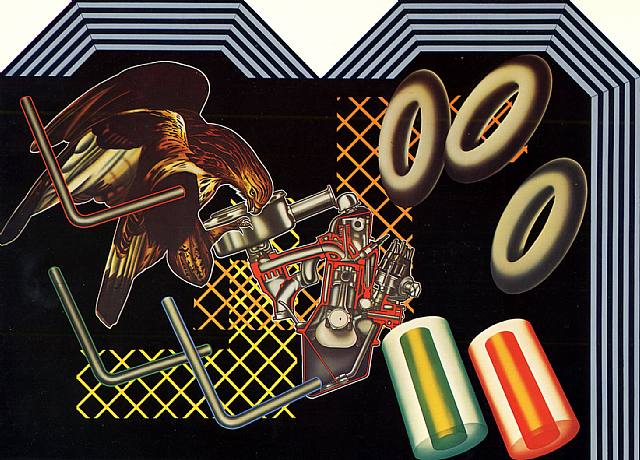

Peter Phillips, the pioneering British pop artist, made some of his earliest (and best known) paintings over 55 years ago now. Yet today, in a world so oversaturated by commercialized imagery and self-generated photos, his work feels particularly relevant. Adopting the visual language of advertising, graphic design, and the Constructivists—while also channeling Dadaist collage—Phillips developed a style that was at once in step with his Pop art contemporaries and wholly distinct from them.

After training for four years at the Birmingham College of Art when he was a teenager, Phillips attended the Royal College of Art. There he first met longtime friends and British Pop art contemporaries David Hockney, Allen Jones, and R.B. Kitaj. Not long after that, he moved to the United States on a fellowship, living and painting in New York, and traveling cross-country with Jones. Numerous trips, solo shows, retrospectives, and special projects later, he was recognized as one of the most important British artists of his generation.

Phillips, who turned 79 this year, now lives and works on the Sunshine Coast of Australia—a place he visited regularly throughout the latter part of his life. His career is quieter now, but he’s still working, revisiting old, unrealized ideas, and experimenting with new techniques. Phillips spoke with artnet, looking back at the trajectory of his career, his relationship with other notable artists, and what his legacy might be.

Peter Phillips, Mediator 3 (1979-80). Courtesy of the artist.

After spending most of your career between Europe, the UK, and the United States, you’re now living and working in Australia. Why have you decided to settle there?

The primary reason I relocated to Australia was to be closer to family. My daughter, Zoe, relocated there five years ago with her husband. Since then, they’ve had a daughter and of course I love being near her.

To tell you the truth, I really like living in Australia—it’s quieter here and the weather’s much nicer. I have my fern trees and tropical garden. It suits me. I first visited the continent in the early 1980s. I drove all the way up to the Daintree, where there were snakes literally hanging from the trees. I never liked snakes. I used to paint them to see if that would help rid me of the fear. It didn’t work. But now that I live here, I think I’ve only seen one snake. I leave them alone, they leave me alone.

Peter Phillips in his studio. Courtesy of the artist.

Are you working on a particular body of work now?

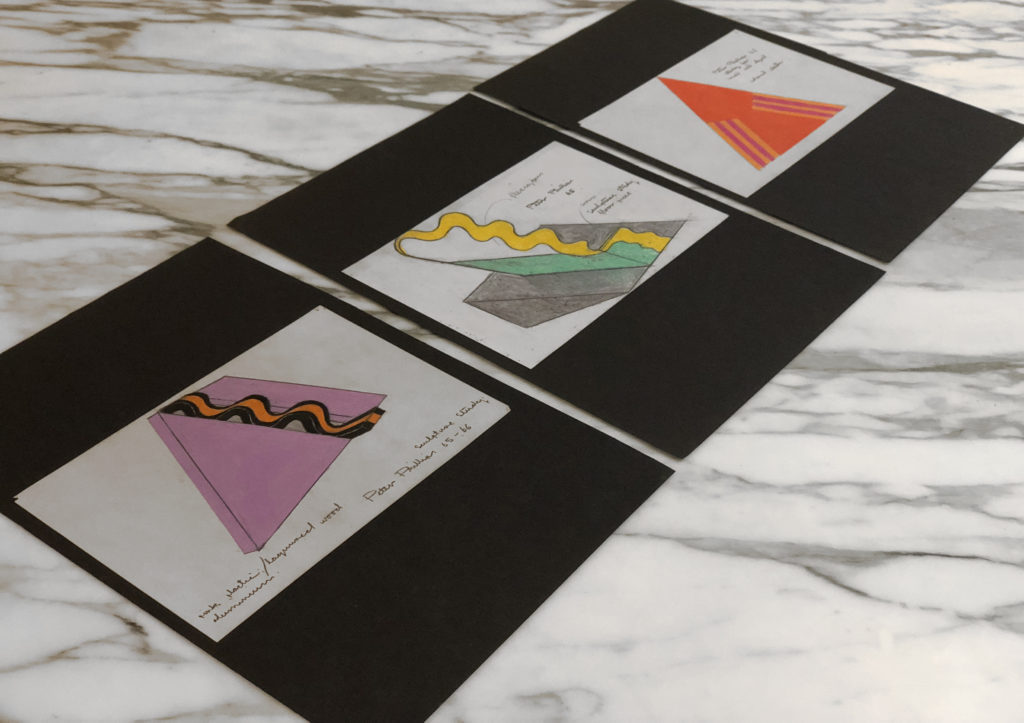

As you get older, the technical aspects of painting become harder. Some of the non-technical aspects too. I recently threw out my back lifting a painting on its easel—that never happened when I was younger. I find myself leveraging the use of technology—painting on a Wacom tablet works well because you can magnify the image and really work on the details. I’m also having fun producing sculptures. Back in the late ‘60s, Gerald Laing and I worked on a project in New York called Hybrid. It was the first consumer research project to do with art. We queried the public on all sorts of preferences they had for art, then worked with a computer scientist at IBM to analyze the results. We made it into a collaborative work, which turned out to be a sculpture. After that, I made some mini sculptures. Jill Kornblee, who owned a gallery at the time in New York, had a show which originally featured them. I designed many more but never got around to producing them. So I’m finally producing sculptures I designed 50 years ago and making some new ones as well.

Sculptural studies from the 1960s, which Phillips is realizing for the first time now. Courtesy of Peter Phillips.

Critics and writers have often compared your collaging techniques to the freewheeling randomness of the Dadaists. To what extent are your paintings random or planned out?

I might call it planned randomness. At the Birmingham Moseley Road School of Art, I studied heraldry, design, and silversmithing. Those skills definitely require careful planning. So even if I’m being random, there’s some subconscious part of me that may have a plan. I called a series of paintings “Random Illusion,” but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s completely random. Perhaps that’s the illusion.

Peter Phillips, The Random Illusion No. 5 (1968). Courtesy of the artist.

In some ways, it seems your style has remained remarkably consistent throughout your career. How would you characterize the ways in which your paintings and prints have changed since the 1950s and ‘60s?

Skill improves as you get older. I’m not talking about technical proficiency or detail, mind you, but skill. Hopefully, since the ’50s and ’60s, my paintings and prints have gotten better. I’ve always tried to experiment. It’s not fun unless I’m trying something new.

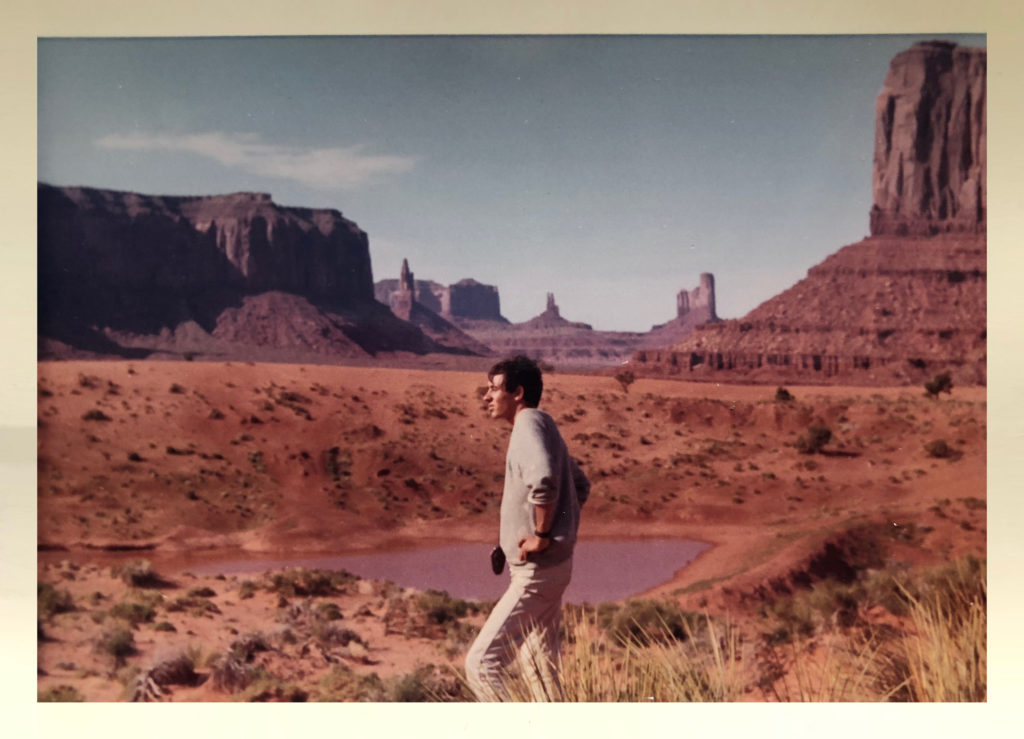

In the mid-’60s, you and Allen Jones embarked on a road trip across North America. What was that trip like?

When I was awarded the Harkness Fellowship, part of the deal was that I needed to spend a few months driving across America. The car, room, and board were all paid for. So I called Allen, who was in the country at the time, and asked if he wanted to join me. He didn’t hesitate. It was a wonderful time.

We just drove. Each night we would look at the map and plan the next day’s journey. When we got to Key West in Florida, we couldn’t find a hotel room for $20, which was our budget. I remember haggling with a hotel owner who wanted $30 and he finally relented. That was a huge discount back then!

From there we drove west. We avoided Dallas because that’s where Kennedy was recently shot. People in the rest of Texas were friendly. A policeman let me ride his bike when he found out I painted motorcycles. When we got to the desert, I was stunned by the beauty and culture. We must have taken a few wrong turns because I remember getting lost in a Navajo reservation.

California was particularly new and interesting to me. We hung out with Billy Al Bengston and that crowd. And then we spent some time staying with Dennis Hopper. Up in northern California, we visited Mel Ramos, whose studio was in his garage of a suburban home.

With the exception of one guy in Chicago who didn’t like our accent, Americans were very friendly and pleased to see foreigners. Most loved our English accents. We were a bit of a novelty. At one point, a bunch of girls thought we were the Beatles.

Peter Phillips and Roy Lichtenstein. Courtesy of the artist.

Who are the strangest, funniest, or most interesting artists you’ve met or worked with in your career? Are there any artists who were nothing like what you imagined them to be?

In art, everyone’s trying to stand out from the crowd. I remember Billy Apple—who changed his name from Barrie Bates—and David Hockney bleached their hair in the toilet in school. Derek Boshier would hang out with all the pop bands—that was cool. I’m particularly grateful to Roy Lichtenstein, who I found very friendly and very helpful. When I first moved to New York, I tried to buy art materials, but the store wouldn’t take my credit. Roy, who was with me, simply put it on his bill. That’s the sort of person he was. I think most artists I’ve met are pretty interesting and unique in their own way.

Peter Phillips on road trip across North America, 1966. Courtesy of the artist.

What are the artworks that changed your life, both as a young artist and as a more established one?

Well, there are two ways to answer that question. On the one hand, every piece I ever created and sold has changed my life. It put food on the table. That’s pretty important for an artist. On the other hand, there are the artworks created by others that kindled my passion. When I was in secondary school, I won an art scholarship/grant that enabled me to travel across Europe with a backpack. I went all over the continent including Paris, Venice, and Florence. I fell in love with classical art—especially Renaissance-era work.

Peter Phillips, Custom Painting No. 7 (1965). Courtesy of the artist.

What, in your mind, is the most significant and game-changing contribution to art that has occurred in your lifetime?

Technology. Marketing.

Peter Phillips. Courtesy of the artist.

As an artist approaching his 80s, do you ever think about legacy? Have you thought about your legacy as an artist will be?

I don’t think about my legacy. That’s for other people to worry about. The last time I painted for other people was at the Royal College of Art when my teachers asked me to paint classical English stuff—landscapes and still life. I didn’t like it, but of course I didn’t want to get kicked out. Once I realized I could make a living painting whatever I liked, I stopped painting for others.

Legacy depends on other people. For me, it’s about doing what I love and doing it as well as I can.