Photographer Isabel Muñoz on Finding Beauty in Unexpected Places, From the Congo to the Yakuza

Sophie Neuendorf

“What are you working on at the moment?” I recently asked the photographer Isabel Muñoz.

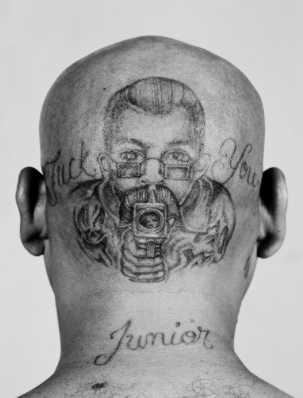

“I’m spending time with the Yakuza in Japan” came the Spanish artist’s surprising response.

The infamous organized crime syndicate is one of the oldest and wealthiest criminal organizations worldwide, and its members can be identified by their full-body tattoos, known as irezumi. These tattoos are often hand-“poked,” where ink is inserted beneath the skin using hand-made needles of sharpened bamboo or steel. The procedure is expensive, painful, and can take years to complete.

Although they’re feared for their ruthlessness, Yakuza members show a different side in front of Muñoz’s lens. During the intimate photo shoots, the artist became privy to their personal sides and aspects of their nature that usually remain hidden from view.

Isabel Muñoz, Maras (2007). Courtesy of the artist.

A truly talented photographer is not only defined by their plays with light, shadow, and composition. In equal part, it’s the photographer’s ability to recognize a sitter’s character and sensibilities, and a sense for their discretion and boundaries. More often than not, Muñoz says, the most difficult part is allowing for time to develop the perfect image—waiting until she is permitted to capture areas of vulnerability

Isabel Muñoz, Mujeres Congo (2015). Courtesy of the artist.

Petite, stubborn, and immensely curious, Muñoz has spent more than half a century traversing the globe and documenting different cultures and traditions, as well as using her platform as an artist to give a voice to those that are voiceless.

Spending time with members of Yakuza was not the first time the photographer has put herself in a dangerous position. One of her most terrifying, and eye-opening, journeys was to the Congo, where she documented the many women and children who have been weaponized in the war and subjected to dehumanizing acts of sexual violence.

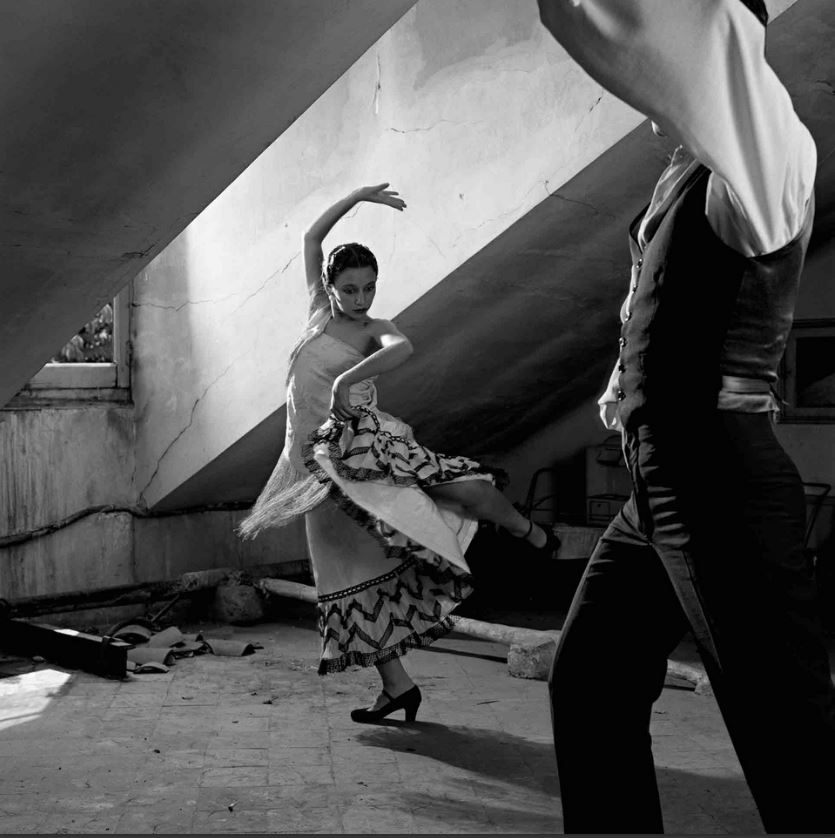

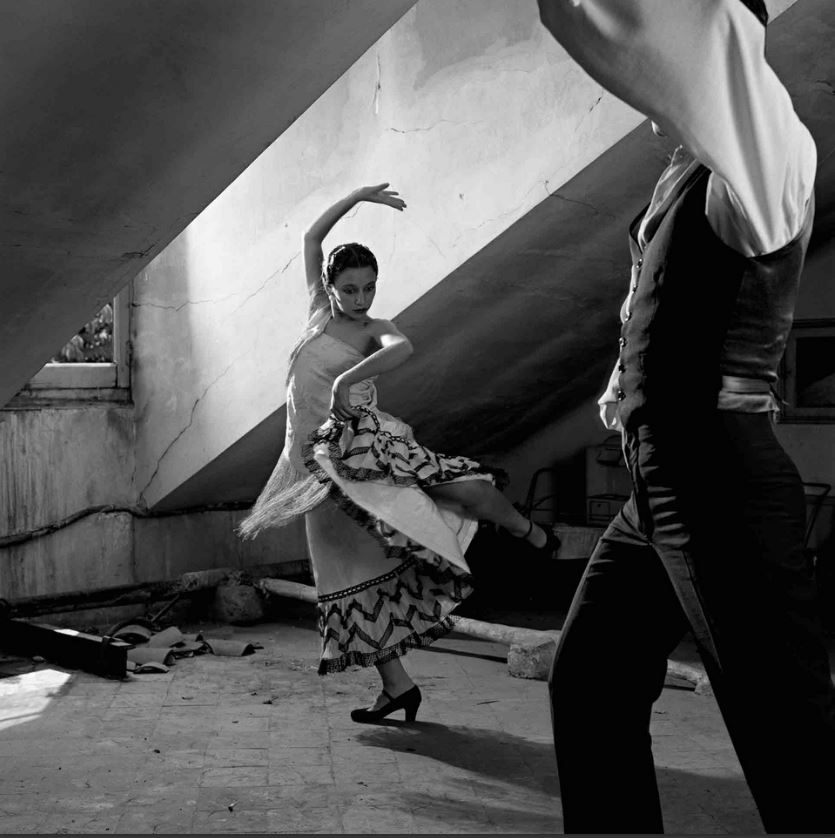

Isabel Muñoz, F20_G (1989). Courtesy of the artist and Blanca Berlin Galeria.

Nonetheless, Muñoz’s series of photos from that time reflect women full of hope and resilience—determined not to remain victims, but to use their survival to change the future for the next generation. (A few months later, the government took action to decrease violence against women and children in Congo.)

Isabel Muñoz, Hijras (2012). Courtesy of the artist.

“No matter where I’ve traveled, and all the cultures I’ve observed, it’s noticeable that we all have one thing in common: all of us experience emotions such as love, hope, or fear. It unites us as humans,” Muñoz says.

The artist’s travels have also taken her to Iran, where she worked on a project that underscored both the differences and many similarities between Spanish and Persian cultures. Beyond their desert-like landscapes, the two countries have both struggled with ideological conflicts internally, but have remained culturally and spiritually untied.

Isabel Muñoz, Deauville (2018). Courtesy of the artist and Blanca Berlin.

How does one come to terms with witnessing so many so much human suffering? “I photograph moments of beauty in all its different facets,” Muñoz says. There’s horses galloping across a deserted beach in Deauville, or Flamenco dancers in motion.

“There will always be darkness,” she says, but “without it, we wouldn’t appreciate and value the light within all of us.”