With His Work Heading to Next Year’s Venice Biennale, the Late Artist Purvis Young Transcends the ‘Outsider’ Label

Artnet Gallery Network

The term “outsider artist” has been controversial since Roger Cardinal first coined it in the early 1970s. While it’s still part of the art-world lexicon, for some gallerists, the phrase feels particularly restrictive.

“It’s limiting, for sure. You’re forced to start off conversations with prospective clients by defending the work,” says veteran New York dealer Skot Foreman. “It’s a handicap. It’s an obstacle, but one that I think can be overcome.”

Foreman should know a thing or two about overcoming this kind of obstacle. One of his biggest and most successful clients is artist Purvis Young, who has been labeled an outsider artist since first being discovered in Miami in the 1970s. Indeed, Young had all the hallmarks that we associate with the outsider perspective: He came from humble origins, living for much of his life in poverty in Overtown, a predominantly black neighborhood on the outskirts of Miami; he was self-trained, picking up all his skill and knowledge from library books rather than art schools; and he often used found objects in his work, from cardboard to crates to doors to just about anything that paint would stick to.

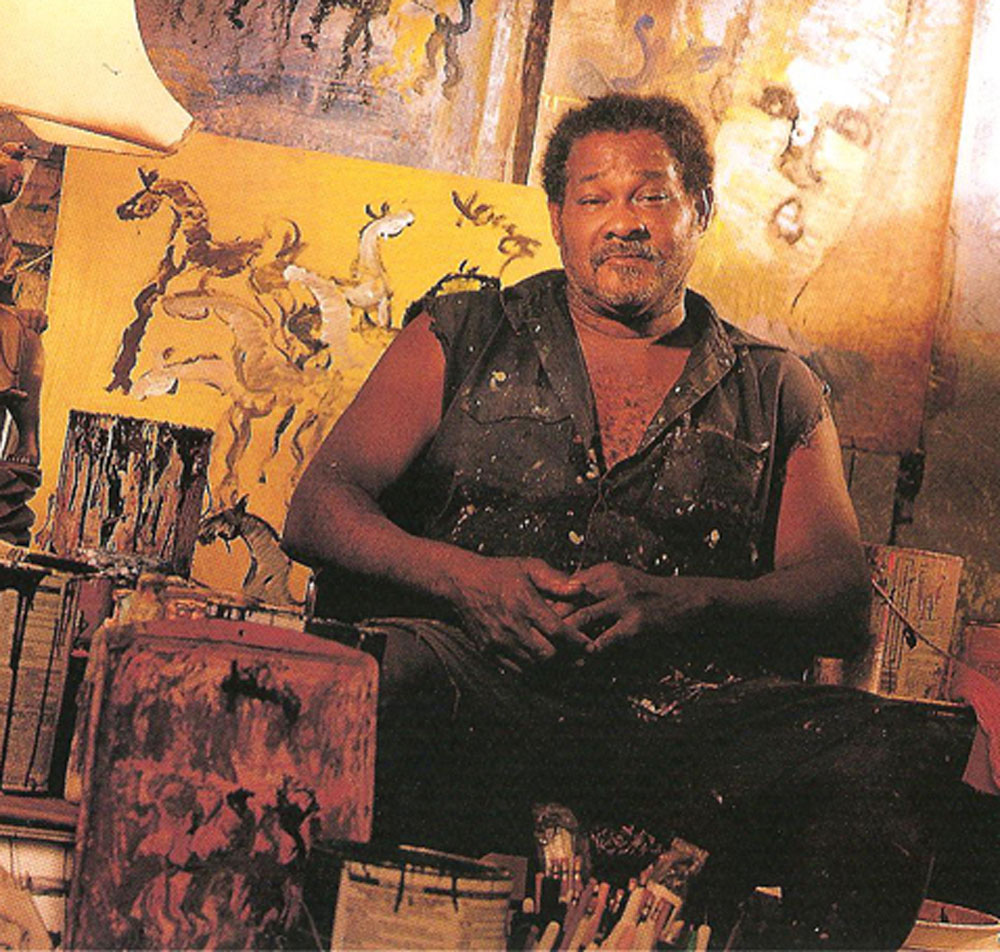

Purvis Young. Courtesy of Skot Foreman Gallery.

Some 50 years later, the “outsider” label still clings to his legacy, despite the fact that his career transcended it time and time again. By nearly any measure, Young was a highly successful artist, and his list of accomplishments has only increased since his death at age 67 in 2010. His work is now included in the collections of some of the nation’s finest institutions, including the American Folk Art Museum, the Bass Museum, the Corcoran Gallery, the High Museum in Atlanta, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Last year, he was included in a major exhibition at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, and his work is currently on view at the Met in “History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation Gift.”

And the swelling of institutional support doesn’t stop there. Next year, Young’s work will be included in the GAA Foundation’s exhibition at the 2019 Venice Biennale—a huge signifier of art-world success, outsider or not.

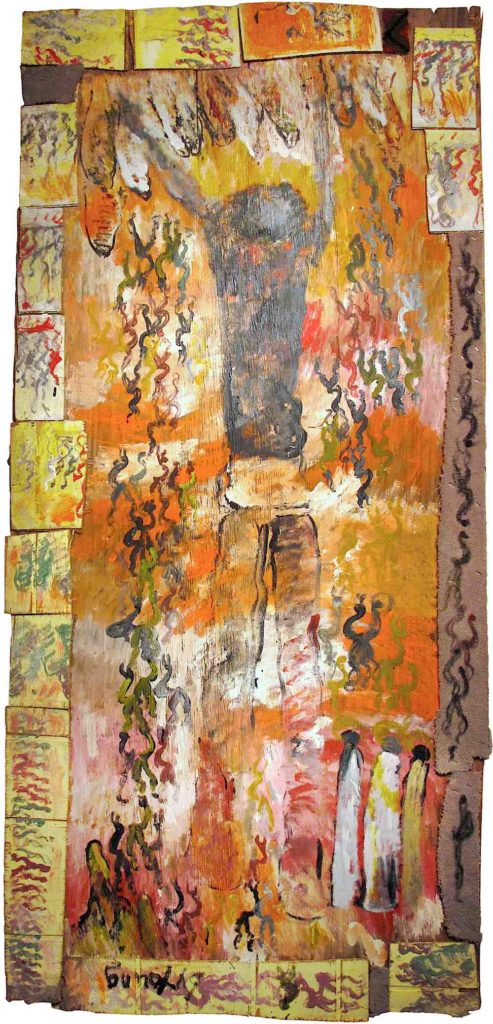

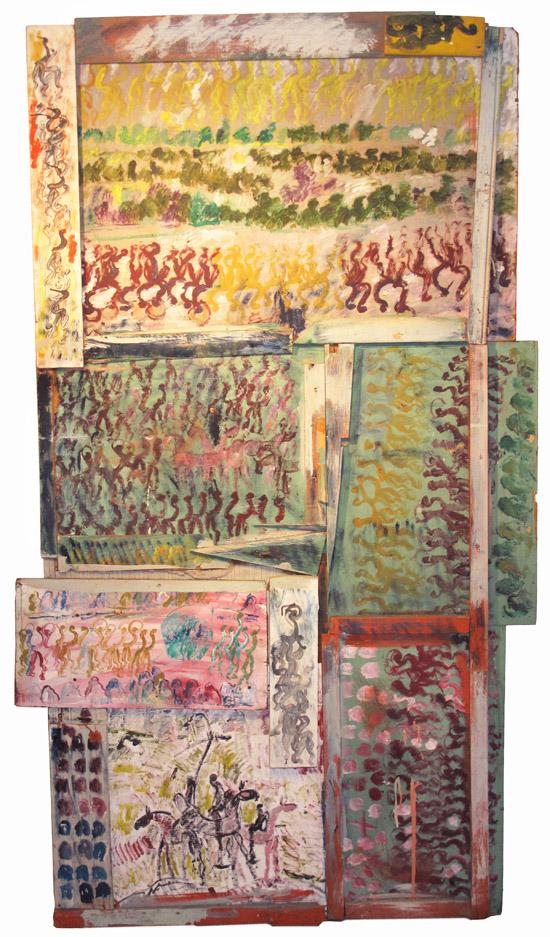

Purvis Young, Celebrate! (c. 1995).Courtesy of Skot Foreman Gallery.

Young was born in the Liberty City neighborhood of Miami in 1943. In his late teens, he was sent to prison for breaking and entering. There, he picked up drawing, finding inspiration in books about artists like Van Gogh, Rembrandt, and El Greco. He continued his practice upon getting out two to three years later, and, inspired by anti-Vietnam murals he had seen on the news, he took his art to an abandoned stretch of wall in a section of Miami called Good Bread Alley.

His mural work soon became well-known, garnering the attention of local news outlets and art institutions. One patron, in particular, took notice—Bernard Davis, a millionaire who owned the Miami Museum of Modern Art. Until his death in 1973, Davis supported Young, providing the artists with supplies, collecting his work, and putting him on the southeastern art-world map.

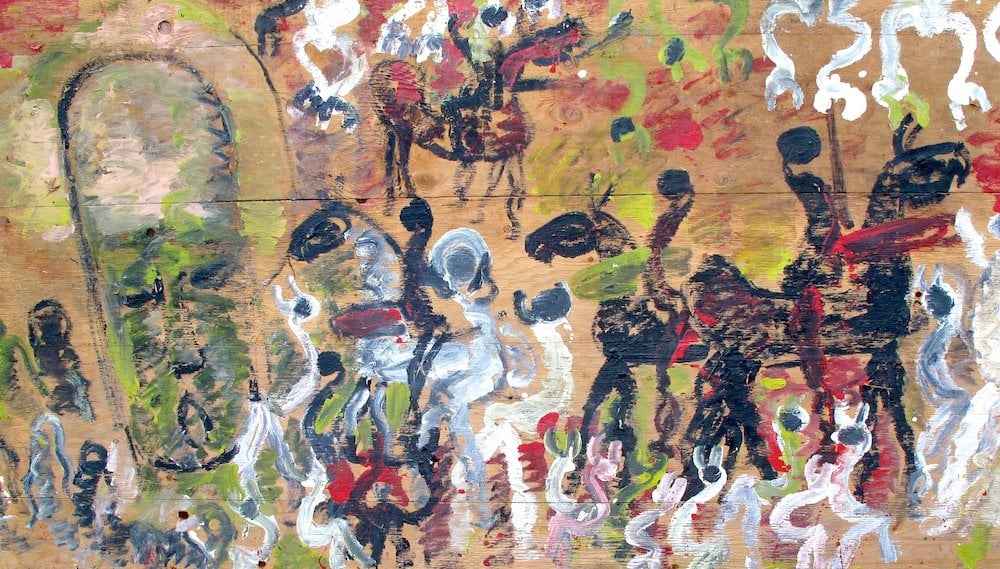

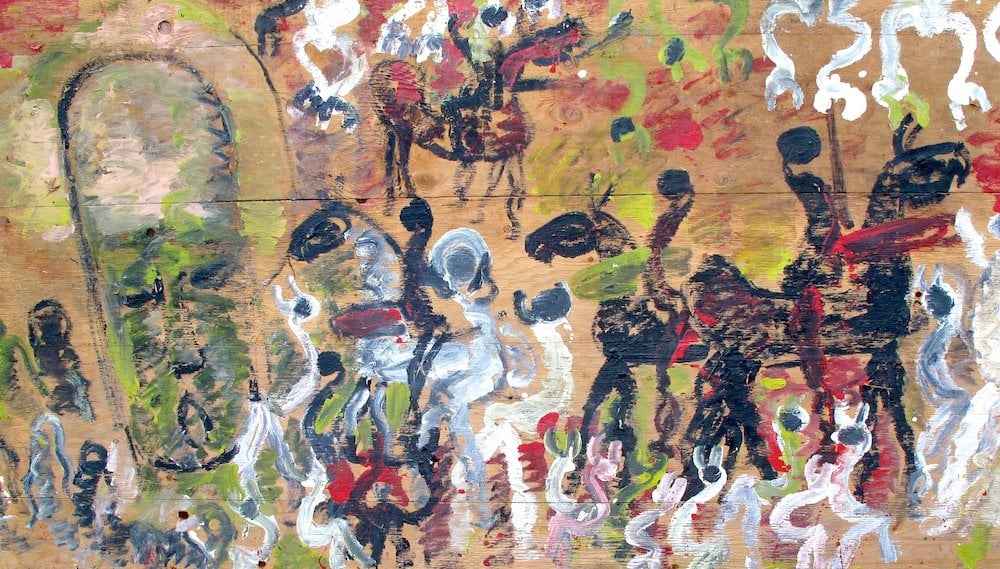

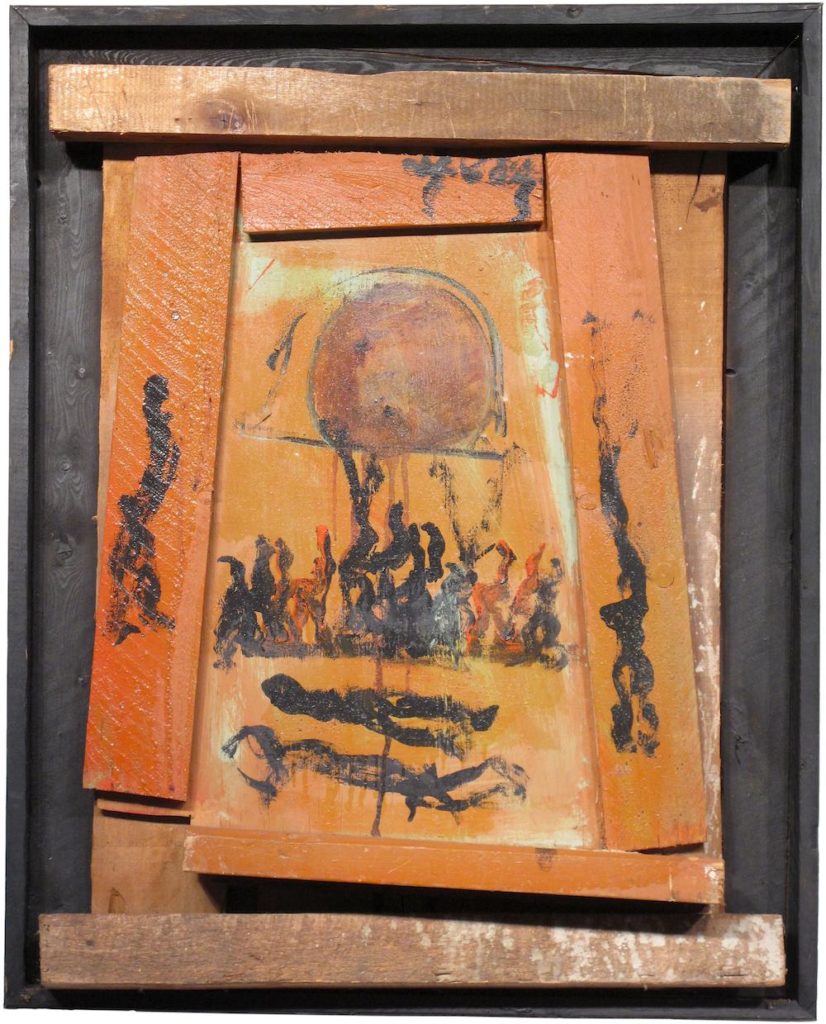

Purvis Young, Processions and Warriors (c.1993). Courtesy of Skot Foreman Gallery.

In the years that followed, Young grew to be something of a local cult icon. Throughout his career, he worked with several gallerists, refusing to be represented by only one name. He began working with Foreman in the early ’90s. An upstart Miami gallerist at the time, Foreman felt something in Young’s work then—something he still feels today.

“It’s still hard for me to put into words what speaks to me, but there’s some sort of frequency or vibration that comes off of his work that captivates me on an energetic level,” Foreman says. “And it still does. When I look at a great Purvis painting, it gets me in the gut.”

In a long, biographical text to be included in a forthcoming Foreman-produced publication, writer Anthony Haden-Guest picked up on a similar energy. Guest traces Young’s outsider roots to a lineage of canonized artists—from Henri Rousseau to Scottie Wilson—before going on to describe what made him special as a creator.

Purvis Young, Feelin the Heat of the System (c. 1992).Courtesy of Skot Foreman Gallery.

“Not a few artists unleash an obsessive/compulsive streak in their art-making, abandoning self-criticism to produce and produce,” Haden-Guest writes. “But when that energy subsides, choice re-asserts itself and it becomes this one! And this! Not for Purvis Young. He had a total lack of interest in fetishizing his output, making it plain that he functioned in a continuum, that it was the energy flow that was consequential and that the resultant drawings were like lava flow from the on-going eruption, constituting the record and the evidence, while he kept moving right along.”

It’s because of this energy that Foreman believes Young’s legacy will continue to grow and that eventually he won’t be considered on the most influential “outsider” or “cult” or “folk” artists of his generation, but simply one of the most influential, period. The market for the artist’s work has already grown significantly since his untimely death—Foreman notes that it’s particularly popular with people who collect neo-expressionism, street art, and work by contemporary black artists. There’s also a strong collector base of Young’s work in Switzerland, Germany, and Denmark.

Purvis Young, Longjoint (c. 1990). Courtesy of Skot Foreman Gallery.

“I believe that he’ll rise above the ‘outsider’ conversation,” Foreman says. “It’s certainly going to take time. It’s going to take more institutional support and more important surveys on an international level, where more people can get exposed to the work, but his work is more complex than typical outsider work. It’s much more layered. It taps into so much more than what the outsider definition connotes.”