Bonhams’s Ralph Taylor on Charting a Course for Auction House Success, Through Frieze Week and Beyond

Artnet Gallery Network

In recent years, Bonhams hasn’t enjoyed the clout of other auction houses, especially in contemporary art—but that may be starting to change. Over the course of the last four years, Ralph Taylor, Bonhams’s Global Head of Post-War and Contemporary Art, has overseen significant growth in his department, including a roughly 30 percent increase in sell-through rate and a 400 percent rise in annual turnover.

This year, opposite Frieze week, Bonhams mounts a private show, “Richard Lin: Selected Works from the Artist’s Estate.” It marks the first European retrospective exhibition of the Taiwan-born minimalist artist, whose market has exploded in recent years. On view through Friday, October 12 at Bonhams’s New Bond Street location, the exhibition brings together 22 works that span three decades of the late artist’s career.

The exhibition comes on the heels of the major announcement last month that the 222-year-old auction house was purchased by the London-based private equity firm Epiris. While the true significance of that change is yet to be seen, this is nonetheless a big moment for Bonhams. Just ahead of Frieze week 2018, the department head spoke with artnet News about his innovative strategies and where he plans to take his department from here.

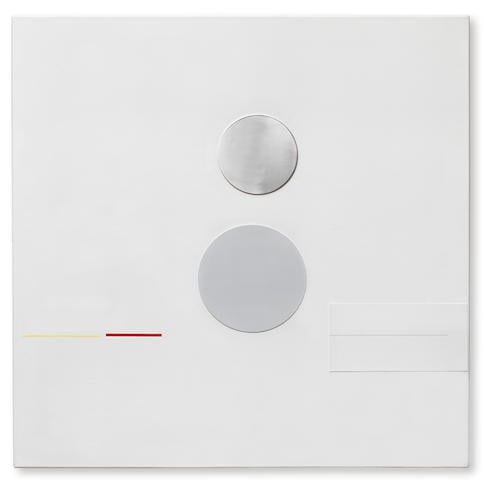

Richard Lin, Untitled (The Black Sun) (1958-60). Courtesy of Bonhams.

Since 2015, under your leadership, the Bonhams Post-War and Contemporary Art department has mounted an exhibition during Frieze week rather than a sale, as other auction houses do. What’s behind this strategy?

Coming in, I had said that I genuinely believed that two sales plus an exhibition per year will make more money and be more profitable than three or even four sales, which was what the structure was before. We’re much better when we can be nimble, when we can be creative. And if we’re tied to the overwhelming auction schedule, then you’re quite limited.

Also, if you’re a department that, in its history, hasn’t sold works by certain successful artists, how are you going to convince a client to give one to you? We’re very strategic with our clients; we tell them what we’re good at and why.

The exhibitions really came about because it was a way of us giving something to people that they’re just not going to get elsewhere. During Frieze, when everyone’s in town, if we’re just offering another auction, that’s not necessarily a point of difference. We don’t usually think in terms of the differences and similarities to the opposition, but I try to put myself into the mind of the collector and say, ‘What does he or she want to do in London for those five days during October?’

I think they’re much more excited to come to an exhibition about a significant, underappreciated artist than seeing an auction—we can do that at other times of the year. For us, it’s about the long term. We may not immediately reap the rewards we would with a sale, but several months later you’ll be incredibly pleased that you made the effort all that time ago. So that’s how it works.

Richard Lin is the latest example of this. He is indisputably the artist most in demand at the moment in the Hong Kong sales when you take Kusama out of it. The competition for his work has become fierce; the prices keep going up and up. And his works are very hard to find. We’ve got 22 works in the exhibition, which is being produced in association with all five of the artist’s children. It’s the first major show of the artist outside of Taiwan ever. It’s very exciting.

Richard Lin is an interesting figure. He’s not nearly as well known in Europe and America as he is in Taiwan and other parts of Asia. Why do you think that is?

He moved to the UK as a teenager, and was schooled here, went to university, moved to Normandy, then lived in Wales for a quite a long period of time. Historically, his work would sell in the modern British art fairs. The work owes a debt to artists like Ben Nicholson and Victor Pasmore—artists who are familiar with the British cultural world—but as an artist, he’s kind of unique.

Interest in his work is enormous. He’s the only contemporary artist that the National Palace Museum in Taipei has actually bought, and the Tate has 12 of his works in its permanent collection, which is a huge amount. He had a show at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London in 1958 and was in Documenta 3 in 1964.

He was a big deal, a very important figure, but for a long time, he was just not that well-known globally. The body of work survived intact; it didn’t veer off into strange trajectories. He’s a huge figure for British collectors. He’s someone we can really look towards as an exemplar of a movement.

We have a selection of works in our forthcoming sale in November from the estate and another one from a separate lender—all of which are also going to be in the exhibition.

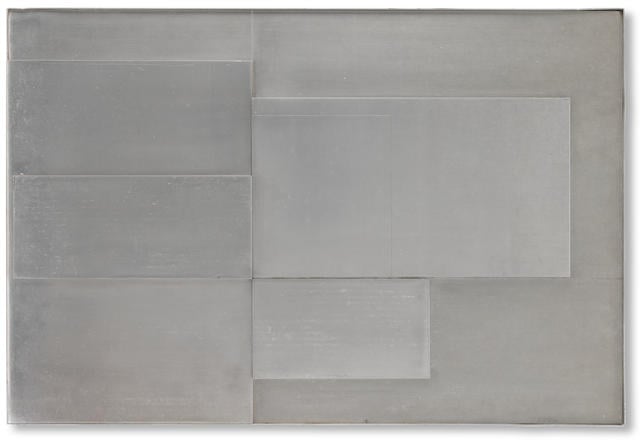

Richard Lin, Metal Relief: March 1961 (1961). Courtesy of Bonhams.

Let’s talk about the growth of the department during your tenure. Since you started in 2014, the department’s sell-through rate, annual turnover, and average lot value have all increased substantially. How have you been able to achieve that progress?

There was a lot of potential for growth when I arrived in 2014. Sales were much lower then.

With the exception of the odd lovely work, the average price was somewhere between £4,000 and £7,000. While decent, that’s not going to encourage people to consign, because context is everything. Vendors care about their work; they don’t care about what the total of the sale is.

So the idea was to eliminate anything that wasn’t up to standard, to be very, very strict in curating the sale. The lot count went down from 170 to 40 or 50, but the average lot price went up to £60, £100, £140, and eventually to £190, which is what it is now.

We’re a Regency-era auction house. We’re all over the world now, with massive offices on Madison Avenue in New York and New Bond Street in London. We can deliver an evening sale, but our evening sale lots—around 50, usually—will go from $2 million down to $10,000, rather than $20 million down to a $100,000. That’s something that we are uniquely positioned to do.

Having that kind of strategy and structure means that you’re much better suited to certain types of artists. It’s not that we don’t want work by people like Jeff Koons in our sales—of course I’d be very happy to work with a Jeff Koons—it’s just not a priority. Where we’re very strong is in artists who’ve been historically overlooked. That’s become a bit of a buzz-phrase, I know, but it’s something we’ve been doing since day one.

We put a work by Wojciech Fangor on the front cover—he’s an underappreciated Polish op artist. He’s a good example. We’ve broken his auction record six or seven times in the last two years. Now, suddenly, there are people more interested in work like this, and you’re seeing it grow in value. That’s really where we’re putting our energy. We can be really focused on that rather than just putting in a secondary work by a Jeff Koons or someone else, which is less exciting for our audience.

In previous interviews, you’ve eluded to your efforts to boost the credibility of the department, trying to get it up to par with the postwar and contemporary departments of competitors. Where are you in that pursuit?

I think we’re already there. It started years ago, around the time I first started here, with a conversation with a client, whom I knew really well. I asked him for a painting; it was worth £100,000 pounds—a lot, but not too aggressive.

He said to me, ‘I like you a lot, I want to support you and I believe that you’ll sell it, but I think others will sell it for more.’ And so I thought, ‘Okay, I’ll come back in a year and I will prove to you what I’m saying.’

That was the biggest challenge early on—breaking that vicious cycle. Let’s make sure that if we’re selling works, we’re selling them to direct comparables to the other auction houses. It was very hard in the first couple of sales to drum into the community, to the company, and to our audience, that this is what we’re trying to do.

And we’ve had some success. Our sell-through rate was 65 percent at the time; it’s now well into the 90s .That’s where the credibility comes from. And it’s been repeated. It’s not a one-off; it’s every single season. The selling rate is always over 90 percent now, it’s always a high average price value—it doesn’t matter what the content is.

Richard Lin, Painting Relief (1961). Courtesy of Bonhams.

Approaching that goal as you are now—obtaining the kind of credibility you sought to bring to the department four years ago—how will you shift your strategy moving forward?

That’s a really good question. You’re absolutely right—we’re approaching that point now, and it coincides with new ownership.

We’ve come a long way since the beginning. It used to be that a lot of car collectors knew Bonhams well, and those car collectors also collected contemporary art, but they were not necessarily on board with the fact that we did both. We fought through that phase. Now we have a profile that people know.

The strategy has always been to be profitable. We have fewer sales now, but they are still very profitable. We’re not eliminating sellable material just to have a purer product. For us, it’s about making sure that we do a good job for our clients and that we’re in a position to reap the benefits of that.

The same thing is true for these exhibitions. The exhibitions are expensive things to do, but they have commercial elements built into them—there will always be some element of private sale, and there’s always an auction consignment part to it as well. Everything feeds into one another.

Now, at this period of change, it’s just a matter of querying the model that we have in place. We’ll also be doing more in America and in Asia. We already have a strong presence in those places, but now it’s about bringing this kind of consistency and excellence across the board and increasing the volume. Strategically it’s about reinforcing the foundations that we’ve built and then growing organically on top of that, not just using the auction house dark arts to manipulate the perception of what we’re doing.

It’s about substantial and repeatable growth. That’s the brand.