How German Artist Robert Janitz Uses Unconventional Materials to Paint ‘an Escape to Greener Pastures’

Artnet Gallery Network

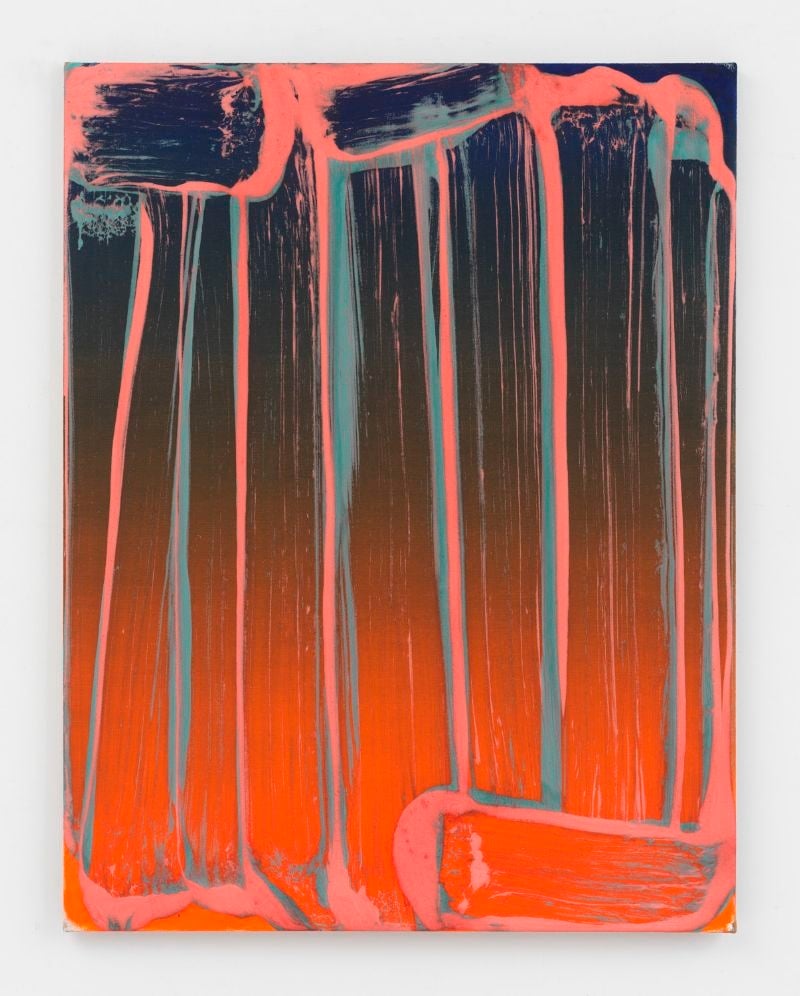

Brooklyn-based German artist Robert Janitz takes a practical approach to painting, buying his brushes from hardware shops and mixing flour and wax into his paints. He has likened his technique to “buttering a piece of toast.” His canvases, full of bold vertical strokes, conjure emptied storefronts with whitewashed windows, among other effects.

On the occasion of “Change In Paradise,” his current exhibition at König London, Janitz sat down with writer Hettie Judah to discuss his unconventional materials, the deceptive simplicity of his work, and more.

I first saw your work in a show that Bob Nickas curated at the Maramotti Collection and I was very struck by it. There was a particularly large painting, about eight feet tall, in a papal purple. Like those on view at König, it was a very reduced work in thick, intensely colored wax. I kept thinking about how that first giant brushstroke must have felt like a leap, like jumping straight into something wet. And I kept coming to this idea of vertigo, because these painting give you nowhere to hide. It’s all enormous sculptural marks. Do you get that sense of vertigo?

I am a shy person, and the idea of expressing myself—even with only myself as an audience—feels like something I have to deal with before painting.

Robert Janitz, Sosumi (2019). Courtesy of König London. Photograph by Damian Griffiths.

You have talked about the idea of painting as a performance. Do you feel you need to create a facade to approach making a painting—to create some kind of a formal sense of who you are as a person in creating a painting?

Yes. At some point I felt I was good at acting, that it adds a playfulness to my range of being. This performance also takes away from a sense of seriousness and allows me to sidestep the historical burden of painting.

How does this performance side of the work manifest? You’ve used the term “dandy painter,” as if you have a sort of persona. The word “dandy” brings an association of flamboyance.

The term came into focus when I was living in Paris. Baudelaire was a key figure in forming the idea of the artist in modern life and what that could be. Susan Sontag and her writings on the camp aesthetic were also important. Probably because I kept switching cultures, from Germany to France, I felt I got a completely different perspective on myself. And then from France to the US, again a different perspective. I found when I arrived to the US a notion of freedom that you can basically be who you want to be. I didn’t experience that before in Europe, where there were a certain set of rules and you tried to get by within them. In the US it felt like there were no rules: you have to manifest what you want. Maybe all of this comes together as the actor or the penniless artist…

Installation view of “Robert Janitz: Change In Paradise,” 2019. Courtesy of König London. Photograph by Damian Griffiths.

When we spoke before, I was interested in how you imposed rules and restraints on yourself. It seems like you need that pressure of being constrained in some way. Moving to America and suddenly feeling that you had no rules, that you could do anything you wanted, be any character, was that stimulating or was it terrifying?

I experienced it as liberating and not terrifying. On the contrary, I think I felt emotionally restrained in France, maybe partly also because of my not knowing what painting was for me—or what I wanted to paint—and trying these systems of mark-making just to keep busy and paint something. I think that straitjacket wore off at some point. After years of following a regimen it became ridiculous and slowly disintegrated. With my cultural shift, it was a good moment for my work to open up.

How did that transformation manifest itself in the work you were producing in France and the work you were producing in New York?

For a couple of years, I had set up a very simple system of mark making: I would repeat these loopy lines with cyan, magenta, yellow, and white. That was my system and I made dozens of paintings that all looked alike. After five years the lines fell apart. I still kept the colors but it shifted to a horizontal orientation. These first loopy lines from 18 years ago were made in acrylic so they didn’t mix much. Then I got into oil painting where more happens with the landing of the strokes.

Your recent works use a mixture of materials that you’ve concocted yourself. When did you start working with more unconventional materials?

New York is where the playfulness happened that allowed me to include flour, for example, and more abject materials, as well as different sizes of brushes.

Installation view of “Robert Janitz: Change In Paradise,” 2019. Courtesy of König London. Photograph by Damian Griffiths.

You don’t use artists’ brushes?

No, these are actually wallpaper paste brushes that I buy in a hardware store in Germany.

What’s the paste you are working with? Flour and wax?

It’s cold wax that gets thinned down in turpentine and it gets this kind of slushy, pancake dough liquidity which incorporates quite a large amount of flour and very little oil paint, mixed in for color.

It feels as though there is a daily practice of gesture and movements that goes into creating these works.

I spend most of my day in the studio. But most of the day I am not really doing much; I feel like I am working the atmosphere. I do Thai-Chi in the studio. I just look. In a way I really wait for the right mindset to settle in, a right sense of pacing and a right sense of decision-making. Then, usually in the later afternoon, by 5 p.m., I start working. But I feel time is necessary. I can’t rush in, throw my coat on the couch and off to the brushes. These last layers are always a one-shot deal, it’s done in one sitting but it’s not done in 10 seconds. The rhythm is also quite a continuous thing, I don’t really speed up and then sit in the corner and think and then rush back. It’s not very dramatic, it’s kind of slow.

What is the difference between the works in which you pushed the paint and works in which you pulled the paint?

These are all made, obviously, on the floor. Pushing the brush allows the paint to be squeezed on the side of the brush and the paint gets pushed to the side. That way what remains is mostly the outline of that gestural mark. Technically, the paint is almost driven away in pushing it. In pulling it’s more evenly spread and more translucent.

Installation view of “Robert Janitz: Change In Paradise,” 2019. Courtesy of König London. Photograph by Damian Griffiths.

You’ve talked about color’s relationship to memory. How does this idea play out in your studio?

At some point I started working on several canvases at the same time so there are maybe five or six that I am working on and I don’t have a particular plan for what the next color will be. In one painting, for example, I’ll think, “this is like the color of the rubber seal my mother used to close glass containers.”

Your mother was a textile weaver. Thinking about pattern and abstraction, can you see a link from that to your own work?

I certainly can see it, but I don’t think of these paintings as abstract now.

How do you think of them? To me they seem like they are portraits of a brushstroke perhaps?

Yes, maybe that’s it.

How did you conceive this particular show for the space?

I was kind of terrified. The problem is obviously the heavy ceiling structure, so I came up with these medium-sized paintings in the row, which hold up against the steel structure. My approach was to be like a theater set. The scenography should start out from the entrance: you come in and there are these weird obstacles that obscure your proper passage into the space. What speaks first is the space, then you turn around and the show actually unfolds.

Installation view of “Robert Janitz: Change In Paradise,” 2019. Courtesy of König London. Photograph by Damian Griffiths.

The “obstacles” are kind of like cow benches.

Yes. I’ve used the shape in a show in New York previously, but made out of concrete. It made sense for me to make them out of this white wall kind of material for this show. The shape itself was inspired by a bench in a playground, which had this slanted element that had broken off. Children had been jumping up and down on one end and it bent down and started looking like an animal.

Maybe it’s not you that’s the dandy painter, but maybe these are dandy plantings? You are creating the stage and these are the performers?

In this show I see them more as potential windows. I guess with the title of the show being “Change in Paradise” this could be paradisiacal, but it’s obviously not. So these would allow, almost as through prison bars, an escape to greener pastures.

“Robert Janitz:Change In Paradise” is on view at König London through May 18, 2019.