How Did Life in a Medieval Italian Village Influence Sol Lewitt? A New Exhibition in Naples Asks, and Answers

Katie White

In 1980, Sol Lewitt, the great American Minimalist and conceptual artist, left the hurried fervor of the New York art world for the medieval Italian village of Spoleto, an area he had been introduced to by the gallerist Marilena Bonomo in 1971.

Lewitt’s later shift to color (he previously used mostly black and white) is often credit to his move, and the many frescoes he discovered in Italy. But beyond his visual cues, in Italy Lewitt was taken in by a network of supportive gallerists, curators, and artists, including the likes of Alberto Boetti and Jannis Kounellis.

Installation view of “Sol LeWitt: Lines, Forms, Volumes, 1970s to Present,” 2019. Courtesy of Galleria Alfonso Artiaco.

Now, in “Sol LeWitt: Lines, Forms, Volumes, 1970s to Present” at Galleria Alfonso Artiaco in Naples, a selection works dating from 1974 to 2005 are highlighted, including six wall drawings recreated in the gallery’s centuries-old rooms.

Curated by Lindsay Aveilhé, the author of Lewitt’s catalogue raisonné, the exhibition is a stirring reminder of the centrality of “idea” in Lewitt’s work. Recently, we talked with Aveilhé who shared her thoughts on the influence of the Italian landscape in his work, Lewitt’s relationship to Arte Povera, and more.

Installation view of “Sol LeWitt: Lines, Forms, Volumes, 1970s to Present,” 2019. Courtesy of Galleria Alfonso Artiaco.

This exhibition is organized in collaboration with the LeWitt Estate and looks back at 40 years of Lewitt’s career, with works dating up to 2005, just two years before his death. How did you make your selections?

The departure point for me curatorially was LeWitt’s 1975 exhibition in Naples at Lucio Amelio Modern Art Agency. For that exhibition, LeWitt installed a series of “Location” wall drawings superimposed onto those of Daniel Buren’s from his previous exhibition at the gallery. In the first room of “Sol LeWitt: Lines, Forms, Volumes“ you will actually find Wall Drawing #241 installed again for the first time since that exhibition.

The idea was the most important thing for LeWitt, so I wanted the exhibition to convey the evolution of his ideas, but also how everything is intrinsically linked to one another in his practice. I decided to focus on works done in black pencil, crayon, and India ink to let the ideas sing the loudest across the six galleries of the space.

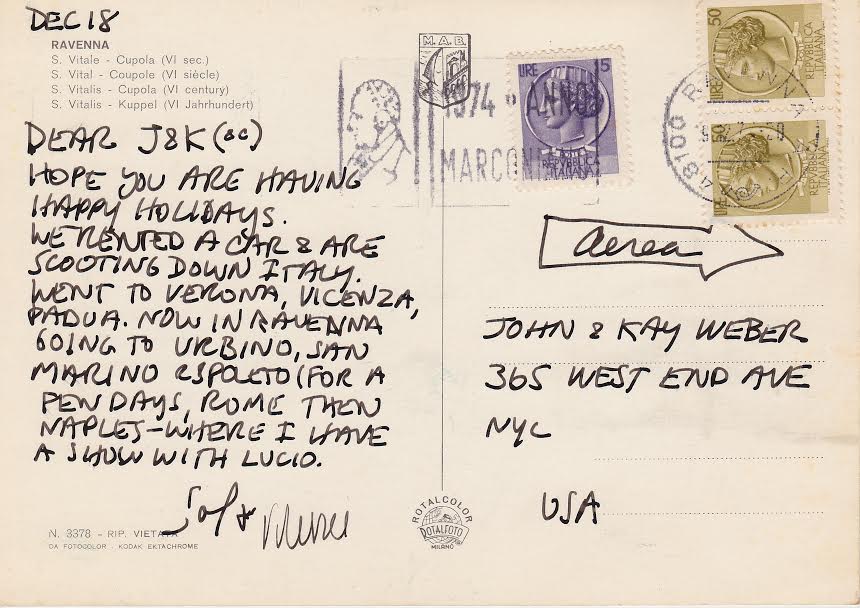

A postcard from Sol Lewitt, post-marked 1974, detailing his travels in Italy.

What was it like recreating these works?

I am based in New York and had only been to Galleria Alfonso Artiaco in person once, but the first time I entered the space, I was captivated by its architectural embellishments (tall ceilings, marble and faux marble doorways, etc.) and how the shuttered windows opened onto the bustling ancient city of Naples. The genius of LeWitt’s work, especially the wall drawings, is that they were often conceived in direct response to the space, the architecture, and the city in which they were exhibited. Having worked on the catalogue raisonné of LeWitt’s wall drawings for seven years, understanding the subtleties of how LeWitt created and later revisited these works was a great asset.

And who actually recreated them? How long did that take?

Once the works were selected and plans created, the plans were passed on to two expert drafters, Nicolai Angelov, based in Berlin, and Andrew Colbert, based in Helsinki. They arrived about a month prior to the opening to begin the installation of the wall drawings. They worked diligently with a team of local artists to complete the wall drawings. I arrived at the end of the installation process and couldn’t have been more elated with the outcome.

Installation view of “Sol LeWitt: Lines, Forms, Volumes, 1970s to Present,” 2019. Courtesy of Galleria Alfonso Artiaco.

LeWitt lived in Italy for nearly a decade. In what ways do you think his adopted home of Spoleto influenced his artwork?

It is often remarked that LeWitt’s transition to color and the use of ink washes was a result of his move to Italy and, in particular, the fresco tradition of his adopted home. After spending quite some time in Spoleto and speaking to his longtime friends there, what can be said is that Spoleto provided LeWitt with the peace and tranquility that he required in his daily practice, far away from the hustle and bustle of New York and the art world. He had a beautiful studio in the center of the small medieval town. He could walk to it from his modest home in the neighboring hillside town of Monteluco via a beautiful aqueduct. His move there really marked for him a renewed freedom of expression.

Lewitt was very interested in Arte Povera. Can you speak to that?

Sol LeWitt was great friends with Boetti, Kounellis, Paolini, Merz, and Penone, among others, and certainly felt an affinity with the Arte Povera artists. He was often shown with them early on in exhibitions such as “Conceptual Art, Arte Povera, Land Art” (1970), curated by Germano Celant and “Contemporanea” (1973), curated by Achille Bonito Oliva. He continued to show with them throughout his life and they often traded works amongst them in a kind of continued show of admiration and respect. Even toward the end of his life, LeWitt maintained that many Italian artists had been undervalued and under-recognized.

As relative contemporaries, the artists of this generation enjoyed a free flowing exchange of ideas that had a lasting impact on all in equal measure. As LeWitt stated in his Sentences on Conceptual Art from 1969, “Ideas do not necessarily proceed in logical order. They may set one off in unexpected directions… .”

Installation view of “Sol LeWitt: Lines, Forms, Volumes, 1970s to Present,” 2019. Courtesy of Galleria Alfonso Artiaco.

The architecture of the gallery and the art works are very obviously from different periods of time, but nevertheless, they seem compatible; there’s a certain shared elegance or monumentality.

What is the most profound I think about the wall drawings are their adaptability to the space. One can see before their eyes where the artist’s idea meets the space, creating a union that is both poetic and powerful. For instance, Wall Drawing #366 Black arcs using the height or length of the wall as a radius, and black arcs using the midpoints of the wall as a radius. The arcs are filled in solid and drawn in India ink can be installed in a variety of ways, with countless options for the combinations of forms created. Like all of the wall drawings, it can never be executed the same way twice.

As the viewer makes their way through the galleries, it is my hope that that one can see through each consecutive work LeWitt’s ever evolving yet linked visual vocabulary.

“Sol LeWitt: Lines, Forms, Volumes, 1970s to Present” is on view through November 2, 2019, Galleria Alfonso Artiaco, Piazzetta Nilo, 7 Naples