What Was Tachisme? A New Show Explores the Lyrical, Lesser-Known Art Movement That Enchanted Paris

Caroline Goldstein

The emergence of Abstract Expressionism in New York City dominates the Western narrative of postwar art history, but less is known about its European counterpoint, Tachisme. Derived from the French word for a spot or stain, tache, the term was first used by critic and curator Michel Tapié to describe the non-geometric style of gestural abstraction taking root in 1950s Paris.

Installation view: “Between Tachisme and Abstract Expressionism: Bluhm, Francis, Jenkins” courtesy of Hollis Taggart Galleries.

In Hollis Taggart Gallery’s enlightening new show “Between Tachisme and Abstract Expressionism,” the Parisian art scene of the era is charted through the work of three American painters who merged experimental American formal techniques with a colorful French sensibility: Norman Bluhm, Sam Francis, and Paul Jenkins.

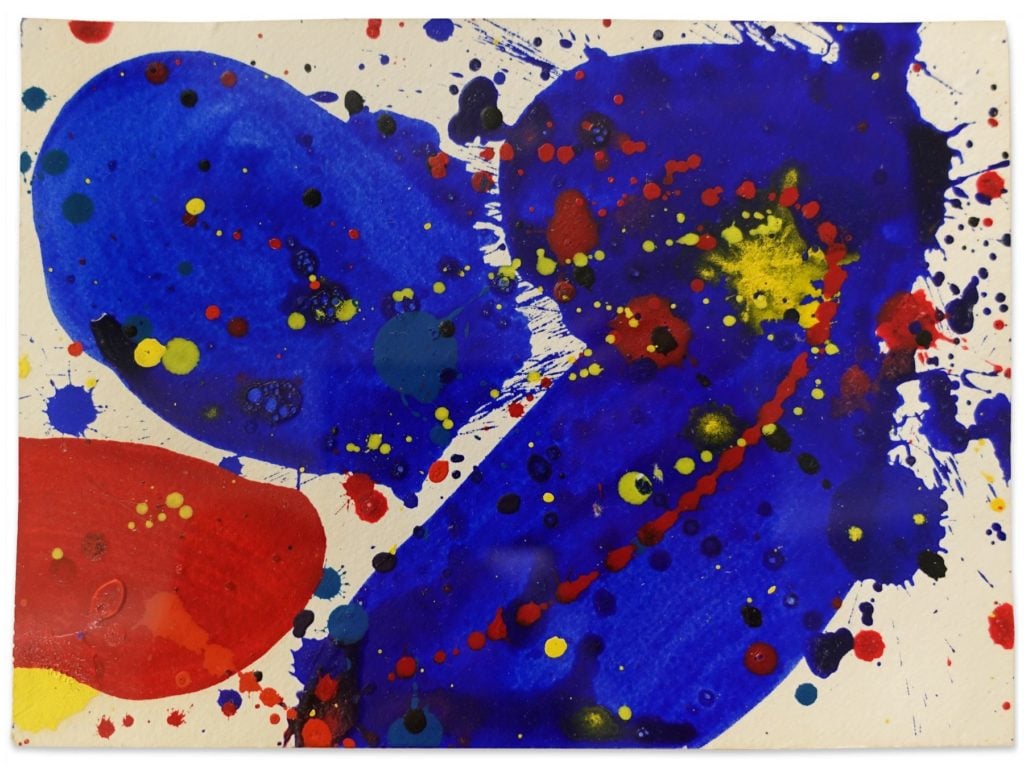

Sam Francis’s Untitled, No. 35 (SF64-628) (1964). Courtesy of Hollis Taggart Galleries.

All three men made their way to Europe with funding from the G.I. Bill between 1947 and 1950 and became close friends, meeting nearly every day. Sam Francis was the most prominent—and charming—of the bunch, heralded in 1956 by TIME as “perhaps the best-known young American painter now working in Europe.” Outshining his friends in success in Paris, his work remains the most identifiable bridge between the New York School of abstraction and the more languid French style.

Norman Bluhm’s Unknown Nature (1956). Courtesy of Hollis Taggart Galleries.

Francis, meanwhile, was a staunch supporter of Paul Jenkins, who activated his paintings by pouring the pigment directly onto canvas, creating luminous washes that became a hallmark of his style. Norman Bluhm, on the other hand, employed frenetic splatters and drips that at once recall Jackson Pollock’s “all-over” technique and Monet’s cloud-like Water Lilies, which he and Francis frequently visited in the nearby Musée de l’Orangerie.

Paul Jenkins’s Phenomena: Hokusai Fall (1974). Courtesy of Hollis Taggart Galleries.

In Hollis Taggart’s new survey of the three artists, the gallery features paintings that span from the nascent stages of their abstract experimentations in 1950s Paris all the way to the ’80s, by which point both Francis and Bluhm were back living in the United States (though Jenkins continued to lead a peripatetic life in Japan, the Caribbean, and beyond). What the show makes clear, however, is that—while much ink has been spilled on the particularly American character of Abstract Expressionism—a distinctly European sensibility inflected some of its lovelier expressions.

“Between Tachisme and Abstract Expressionism: Bluhm, Francis, Jenkins” is on view at Hollis Taggart Gallery through November 10.