Art Dealer Jim Levis on How He Went From Running a Storage Business to Repping Elaine de Kooning

Artnet Gallery Network

By the time he turned 50, Jim Levis was the successful co-founder of an art storage and transportation business. He could have coasted on that to happy retirement, but instead he sold his shares to the business and pursued his dream: becoming an art dealer.

Fast forward nearly 20 years and that dream is very much a reality for Levis, who today operates Levis Fine Art, a gallery with a space in Ossining, New York, and a private viewing facility in Long Island City, Queens. He specializes in postwar American artists—especially those who have been historically overlooked, such as Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, and Beauford Delaney—and has facilitated a number of high-profile museum acquisitions and published several catalogues.

Levis will be the first to tell you that the transition didn’t happen overnight. While he was familiar with the inner workings of the art world, he had a lot to learn about art history, the market, and what it takes to become a successful dealer in a highly competitive field. Hitting the books and soaking up all the knowledge he could from curators, writers, and gallerists, Levis sought to close that gap.

artnet spoke with Levis about this career change and the lessons he learned along the way.

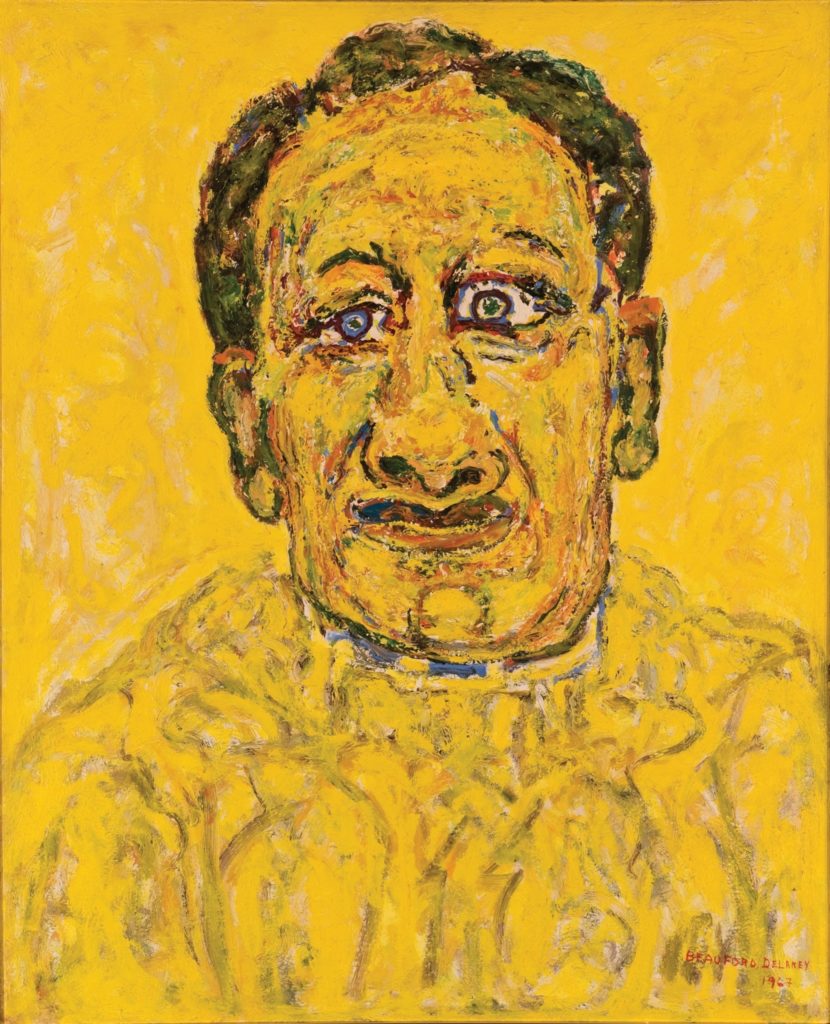

Beauford Delaney, Portrait of Howard Swanson (1967). Collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Courtesy of Levis Fine Art.

Can you tell me a bit about your personal history?

I was raised in a family where fine art, antiques, and music were very important to who we were. My mother used to drag my brother and me to antique shops. It was torture at first, but soon it became a treasure hunt. In my early teens, I took some of my paper route savings and literally decided to buy my own paintings from an antique shop. I was too young to drive so I got my brother to agree to drive me. We took the car and drove over to pick up this enormous painting—a larger and more colorful artwork by the same artist that was in my parents’ home—then snuck it into the house and hung it on the wall where a few smaller paintings had been. My parents were so startled when they walked in.

They moved while I was away at college. When I visited their new home, I noticed my painting had been damaged during the move. I thought if this happened to me, it must be happening to others. This was the catalyst years later for co-founding the Fortress Corporation with my brother.

At Fortress, I learned about fine art from my clients—some of the most knowledgeable curators, conservators, and art advisors in the industry—who shared stories. I was so excited about the artists and their work that when I reached the age of 50, I “handed the keys” of the business over to my brother and started Levis Fine Art.

That must’ve been a hard decision, letting go of a successful business you founded for an unknown direction.

Love, passion, and infinite curiosity are very powerful motivators. When I left Fortress I never looked back. I was most passionate about pre- and post-war Modernism, especially Abstract Expressionism. The idea of learning, discovering, and sharing in this space had captured my heart and imagination.

Jim Levis with the Director and Chief Curator of the Pollock Krasner House, Helen Harrison. Courtesy of Levis Fine Art.

What was the transition like? I imagine that even though you were familiar with the industry, you still had a lot to learn.

I sure did. Even with my Fortress experience and a good eye, I knew it was going to take time to become a recognized and respected resource. Thanks to a small number of knowledgeable dealers, scholars, and critics who believed in me in those early years—including Franklin Riehlman, Gary Snyder, Gertrude Stein, Dee Dee Wigmore, Dore Ashton, Mark Borghi, Tony Fusco, Sandy Smith, and Barbara MacAdam—my transition was easier then I had anticipated. I am grateful to them. That’s not to say that there weren’t others in positions of power and control who, for obvious reasons, tried to deter me. They were a lesson in the dark side of our industry. Those moments were bad surprises, but not a shock. They motivated me to become more creative and devise a better plan, which in hindsight was far more impactful.

In the early years I elected not to have a gallery but instead exhibit at art fairs around the country, including the Boston International Fine Art Show, the Pennsylvania Academy of The Fine Arts fair, the Los Angeles Art Show, and Art20—great experiences, all of them. I began to earn the respect of dealers and curators, and even occasional recognition by critics—including Roberta Smith for whom I have always had great respect. The art drew the clients, and many have become good friends.

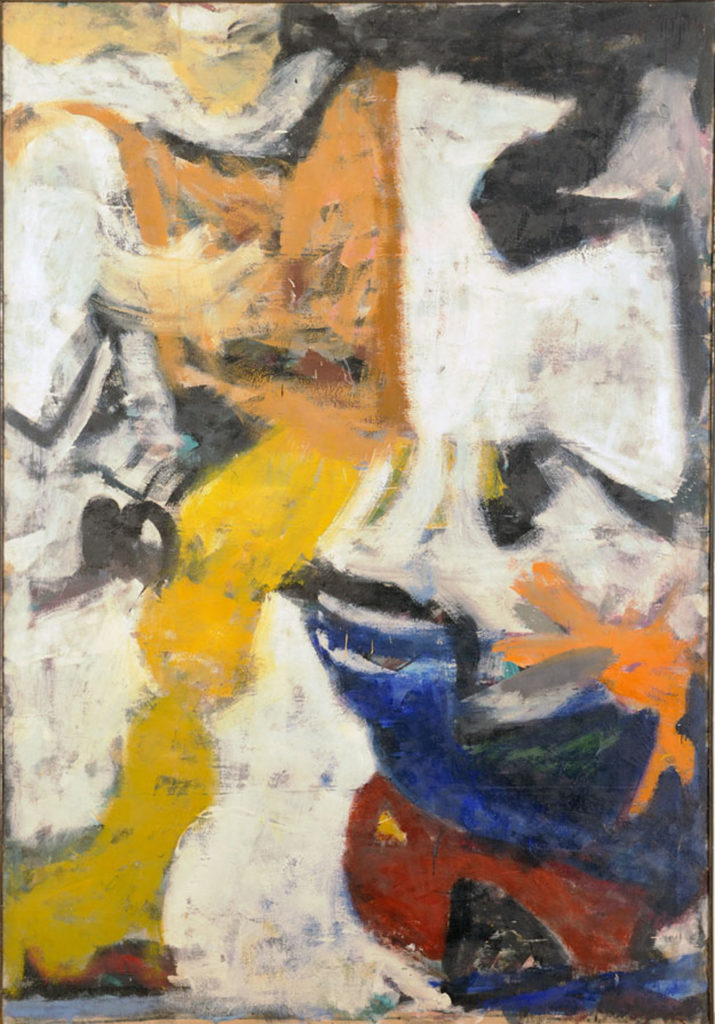

Walking the show floor, it became clear to me that there was relatively little representation of paintings and sculpture by female and African American abstract artists. I quickly learned it had nothing to do with the quality of their work or the strength of their voice. Many had been highly celebrated at the time they created their work, but marginalized by reason of gender and race. This was an “aha” moment. I took the time to go visit with Grace Hartigan, Dore Ashton, Irving Sandler, and others who were very close to the New York School and the American Abstract Artists Association. Learning from these sages was invaluable and memorable. They were very open and excited to share what they experienced and knew. Armed with these new insights, I acquired strong works by Grace Hartigan, Elaine de Kooning, Hedda Sterne, Helen Frankenthaler, Dorothy Dehner, and Ibram Lassaw.

Is this when you started pursuing artists’ estates?

Yes. That set the stage for me to consider taking on the responsibility of managing artists’ estates, where a critical mass of their better work brings economies of scale and the ability to control the quality of the marketing. I was poised to seize the right opportunity at the right time. That time came quickly.

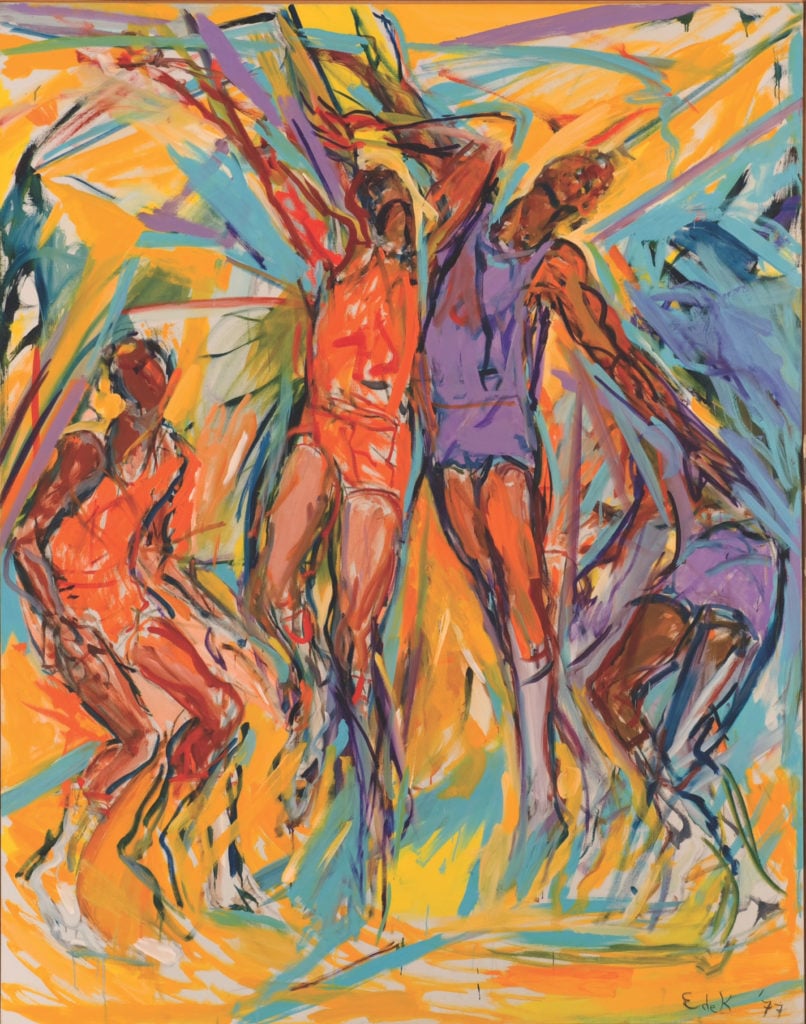

At the beginning of July 4th week in 2007, I received a call from one of Elaine de Kooning’s heirs about potentially representing a significant body of work from her estate. The heir was interviewing four galleries and I was being considered. Well, one of the things I learned in business is that the early bird gets the worm. While all the other, much-larger dealer candidates invited to the table chose to wait until after the holidays, I hopped on a plane right away. I spent three days with the heir organizing, cataloguing, and packing, and secured an art handler to transport the work back to New York. This was an important moment in my career trajectory.

By 2009, female and African American artists’ contributions to modern art were receiving greater attention. It was around this time that I started acquiring artworks by Beauford Delaney. Competition was fierce. But in 2011, an amazing opportunity arose. After much due diligence, I was selected by the estate of Beauford Delaney to represent many of the artist’s outstanding paintings. Sales to collectors and museums opened doors for other private collections of Delaney art being consigned.

Elaine de Kooning, Basketball #40 (1977). Courtesy of Levis Fine Art.

When did you open your first brick-and-mortar gallery?

In 2012, I finally took the plunge with a partner gallerist, Patrick Dawson, to open a 2,500-square-foot, third-floor gallery on West 24th Street in Chelsea, directly across from Mathew Marks Gallery. Mother Nature made it a rough start with Hurricane Sandy. But right after that, my solo show of works by Elaine de Kooning was very exciting, garnering much curatorial and collector interest and great critical review. I was also proud to have two solo exhibitions on Beauford Delaney over the next few years, filled with exciting works from his Paris period. Group shows highlighting de Kooning, Hartigan, Dehner, Lassaw, James Brooks, Kenneth Noland, Leon Polk Smith, and Theodoros Stamos were held almost every other month. Results were well beyond my expectations.

Was there a point in your new career where you felt like you had finally caught up?

I’d say yes—about four years ago, just before the building was sold. It had taken me 15 years to be “an overnight success.” It’s about having passion, a plan, staying focused, starting small, and knowing the right sequence of steps.

Today I choose to no longer have a staffed gallery and instead I hold customized viewings to pre-screened collectors and curators in a private viewing facility. It’s a conversation about quality, not quantity. Eighty percent of my time goes to supporting curatorial initiatives for museum shows, while the other 20 percent goes to private client relationships. Business has never been better.

Grace Hartigan, Portrait of W (1951-52). Courtesy of Levis Fine Art.

How has your decision to embrace collaborations informed your business trajectory?

I’ll never forget receiving a phone call from Brandon Fortune, chief curator of the National Portrait Gallery, in the spring of 2013. I had been introduced to her months earlier and we had a pleasant conversation. She mentioned the possibility of a small exhibition for Elaine de Kooning’s portraiture in one of the museum’s galleries, possibly in 2017 or 2018. Taking the long view, especially for estates, I embraced the idea and let her know I would be ready and willing to help her locate the appropriate works. As luck would have it, she called a few months later to share that the upcoming exhibition for their main gallery was being re-scheduled and asked, if given the opportunity, could I help her locate and secure a significant number of Elaine’s major portraits to be exhibited alongside Elaine’s presidential portrait of John Kennedy—which was owned by the museum—as well as other portraits works of hers within the collection. An enthusiastic “yes!” was my answer, of course. The exhibition, which ran from March 2015 through January 2016, was a great success, sending a clear and positive message to the art world about Elaine.

The catalog, Elaine de Kooning: Portraits, accompanied the exhibition. It has been an amazing resource and is widely distributed around the world. This, and a stream of other publications—namely Helen Harrison’s catalogue for a 2015 exhibition at the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center; Cathy Curtis’s biography, A Generous Vision: The Creative Life of Elaine de Kooning; and Mary Gabriel’s Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement That Changed Modern Art—have highlighted these important female artists and are continuing to raise awareness around the globe.

And collaboration with dealers?

Sharing some of my best inventory with certain dealers has, for the most part, been very successful for me. It runs counter to what a lot of people think. Successful collaboration may decrease my personal financial gain on certain sales, but can markedly increase awareness, especially if you’re representing an under-recognized artist’s estate. In my humble opinion, it fills an important responsibility to the artist’s legacy and heirs. That said, the selection process is heavily reliant on one’s judgment of the character, integrity, and business process of the fellow dealer.

Interior shot of Levis Fine Art’s private viewing room, featuring works by Elaine de Kooning. Courtesy of Levis Fine Art.

You alluded to how tricky it is to rebrand certain artists’ careers, especially when those artists already have an uphill battle. How have you been able to reposition the narrative around them?

I need to fall in love with the art and the story. But it is a non-starter if the artist did not have significant accomplishments and awards, major critical reviews, and important gallery exhibitions to their credit. Then there must be an available strong body of their most telling inventory, that which truly defines their unique contribution. This interview has fleshed out how I contributed directly and indirectly to that narrative including picking the best writers and curators to work with. The results speak for themselves.

To what else, if anything, would you credit your success?

The biggest credit goes to my wife, Jamie, who encourages me to follow my passion.