‘We’re Like an Old Married Couple Now’: Gallerist Bernard Jacobson on Artist William Tillyer, Who He’s Represented for 50 Years

Artnet Gallery Network

Come next year, gallerist Bernard Jacobson and artist William Tillyer will have been working together for 50 years. That’s longer than half the people in the UK have been alive.

“We’re like an old married couple now,” Jacobson tells artnet News, laughing. “I can only say that it’s been a wonderful journey.”

“I’m sure neither of us expected to be together for 50 years,” says Tillyer, a quiet man who celebrated his 80th birthday late last month. “Who could ever dream of it? It just worked out.”

“Well, so far…” Jacobson jokes.

The two met in 1969. Jacobson, a young gallerist in his 20s, had already made a name for himself publishing prints by the premier pop artists of the day. Tillyer—then a 31-old-artist working in printmaking and painting—showed up at the gallery with a portfolio of etchings. For Jacobson, it was “love at first sight.”

Today, Tillyer is one of most decorated British artists of his generation. His work can be found in the collections of the Brooklyn Museum, New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Tate, and the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Given his relentless urge for experimentation and reinvention, he is not the easiest artist to represent; you never know what you’re going to get. Jacobson recalls a story in the mid-’90s when, upon visiting Tillyer’s studio, New York dealer André Emmerich wanted to put on a show of the artist’s work. However, 18 months later, when the works arrived in the gallery for the exhibition, they were nothing like Emmerich remembered. The gallerist was confused. Fortunately, it wasn’t a problem for long: the show quickly sold out.

“William is one of those artists who never stands still,” says Jacobson. “He’s always progressing and progressing and progressing. He’s on a journey.”

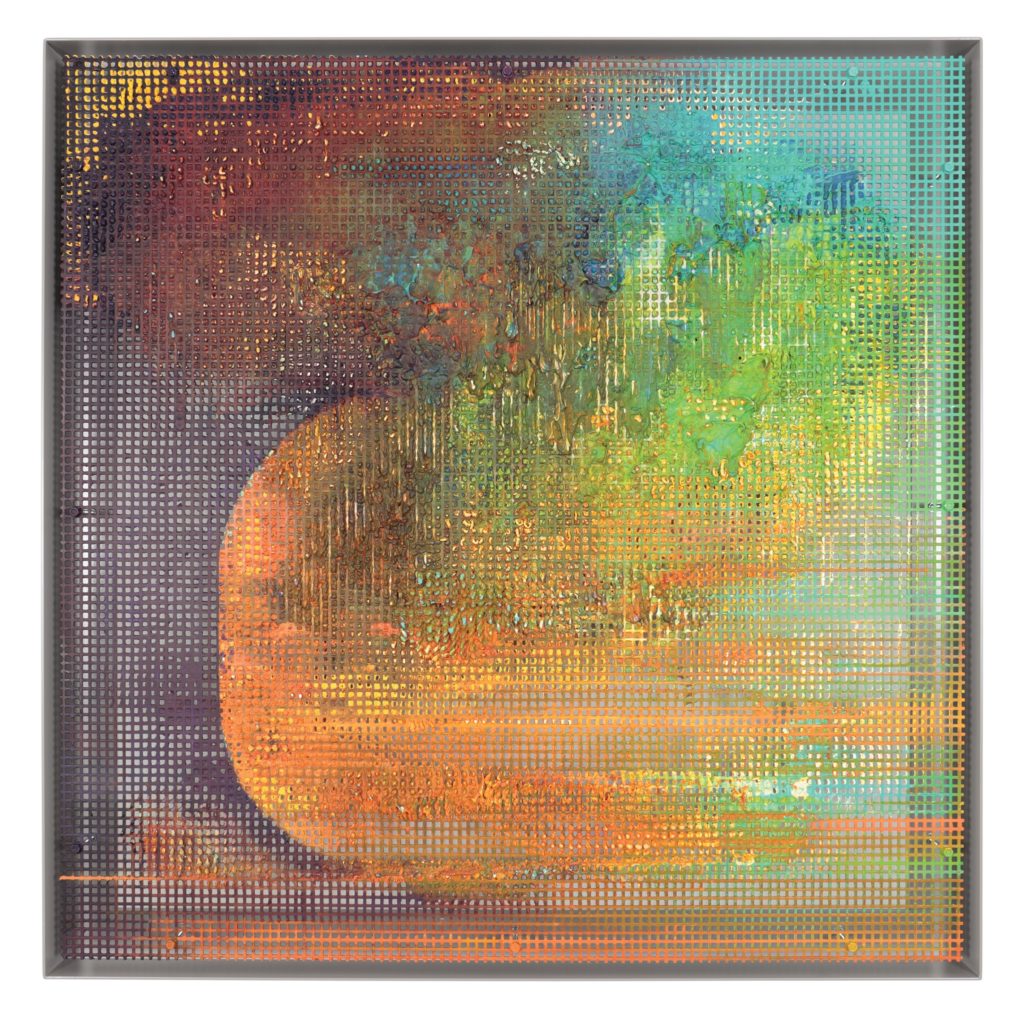

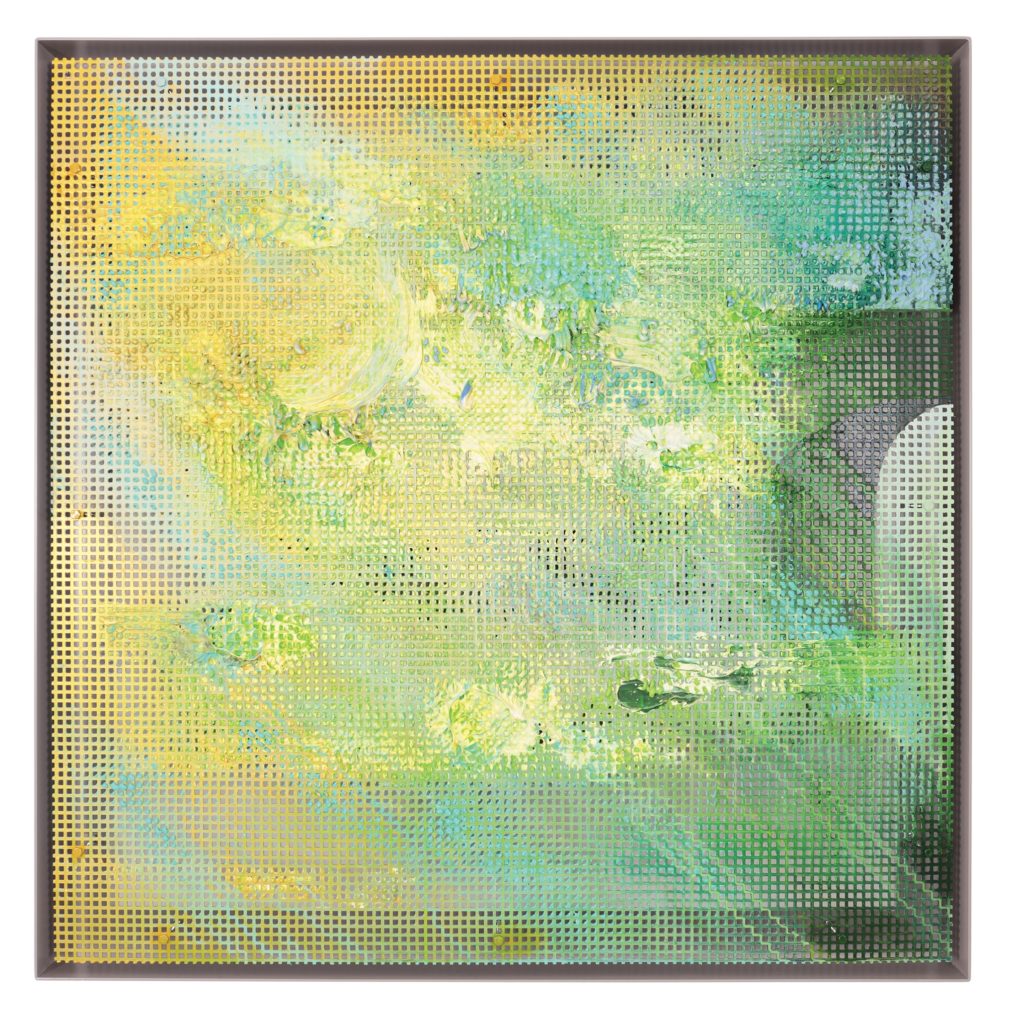

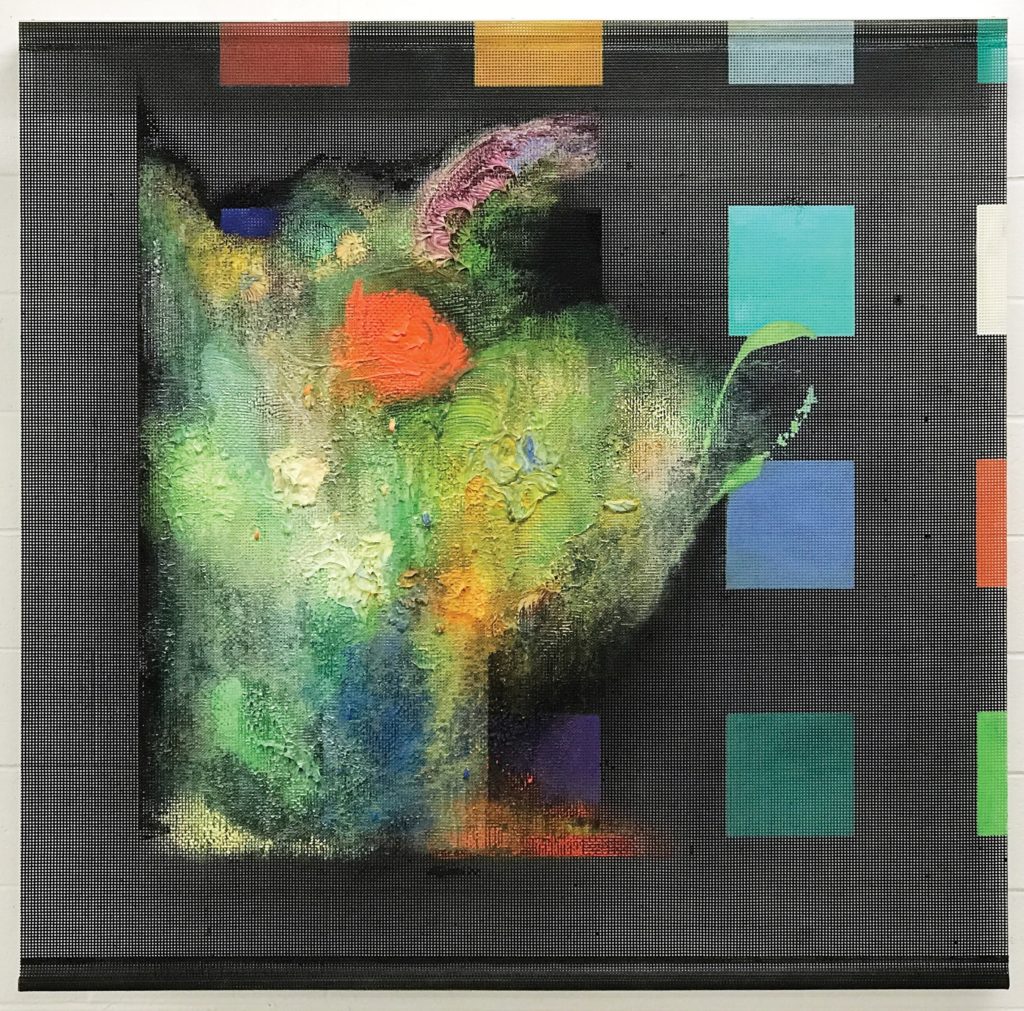

What’s perhaps most impressive is just how genuinely enamored of Tillyer Jacobson still is, 50 years into their relationship. He’s quick to mention that he feels Tillyer is one of the world’s most underappreciated painters. And he’s not just blowing smoke. Jacobson has devoted nearly his whole 2018 program to Tillyer; four of the gallery’s six exhibitions this year are solo shows of his work. The last of the bunch, an exhibition of new paintings on industrial plastic mesh titled “The Golden Striker and Esk Paintings,” is on view at the gallery now.

Jacobson also took three years off to write a full book about Tillyer. Titled the “The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner,” it details the artist’s full life and career, including the many twists and turns his work has taken.

Below is an excerpt from Jacobson’s “The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner,” detailing the first time he and Tillyer met. You can purchase the book here.

William Tillyer, The Golden Striker (2018). Courtesy of Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

William Tillyer is now in his eighties. When I first came across him I was in my twenties and he was just 31. In Art International he had read a feature describing me as the new voice of limited-edition prints, and the year was 1969. I was already involved with Warhol and Lichtenstein and Hockney and Oldenburg. I had already published prints by Malcolm Morley, Robyn Denny, Ivor Abrahams. I could have gone out for a stroll that afternoon, as I often did during those years. If I sold a Warhol print I would set out from my fourth-floor walk-up in Mount Street and wander the tiny park behind the block, or sit at the Italian café on the corner. But I happened to be in my office when Tillyer appeared.

In walks a soft-spoken and slight young man, holding a small black faux-leather case, stuffed with etchings. He was quiet and unassuming, already somewhat defiant. This was Mount Street in Mayfair, opposite Scott’s fish restaurant and above Doug Hayward, tailor to the stars, who included Terence Stamp, Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Laurence Harvey, Terry Donovan the photographer, movie moguls, and more. But I was high above all this, in an L-shaped cupboard for gallery and office at £10 a week, including the use of a secretary. If you wanted to get to my gallery you had to be determined, and Tillyer arrived out of breath, probably from anxiety as much as the climb. “So, let’s see your work…”

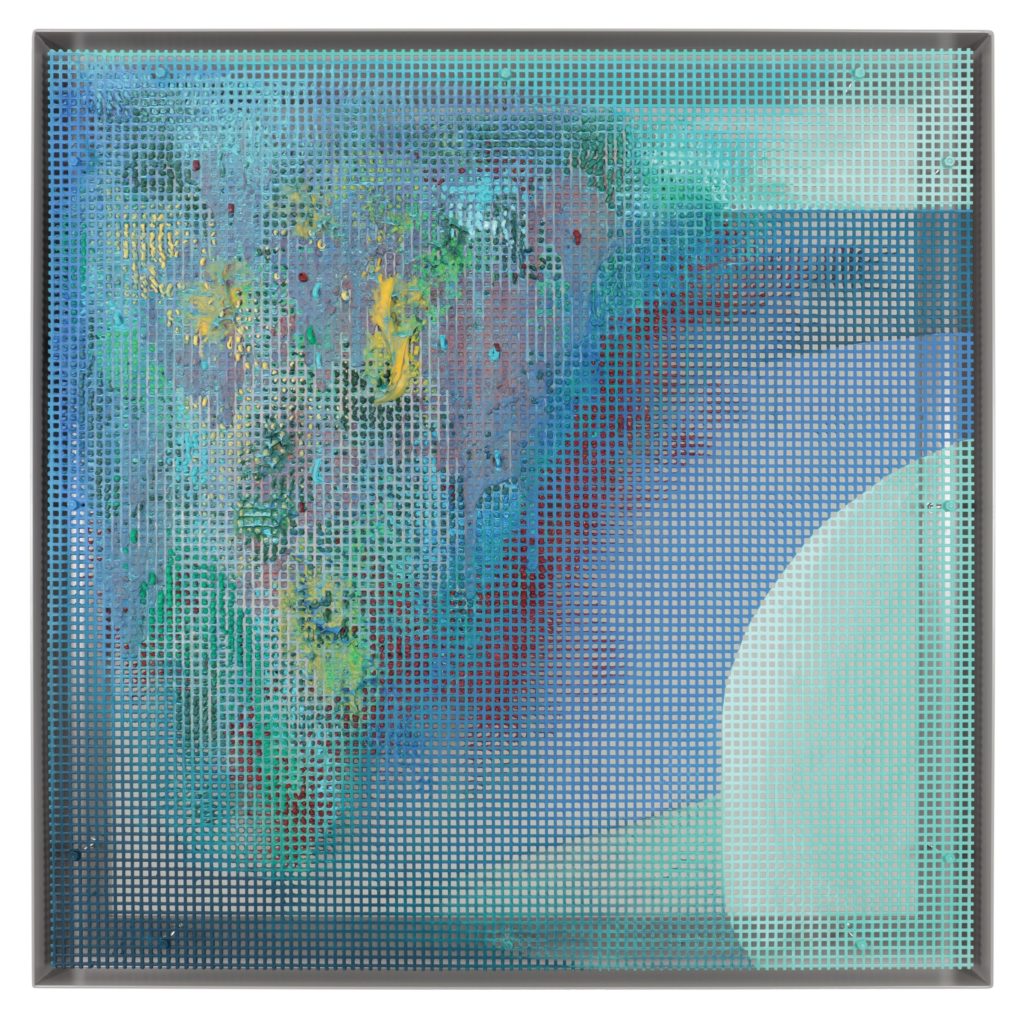

William Tillyer, Esk 2 – Relentless, An English Idyll (2017–18). Courtesy of Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

He unzipped his portfolio and there they were. Those etchings. It was love at first sight. “They are terrific. If you can get a reputation for your paintings I’d be happy to publish your prints.” He shuffled a bit. “But that’s why I came to you,” he replied.

Innocent but with a touch of confidence. I was taken aback. “Open that folder again,” I said, before he had time to vanish back into Mayfair. “OK, I’ll publish this one and that one,” and they were Mrs. Lumsden’s and The Large Birdhouse. His titles were already confident, the etchings done in a one-off cross-hatch technique I had never seen before, where the image appears through an interrupted or broken grid, whose openings or apertures he had created by biting those parts more deeply and which gave the image its reality, its substance and also its light step, its topicality. I instantly realized that I was looking at a new language, one which I did not truly comprehend, although in time I thought I would. We made 25 copies of each. I got to work in earnest, and within a very short time had sold them all.

To put things in a perspective of sorts, if Cézanne had nowhere to go but Vollard, and if Manet, Monet, and Pissarro had nowhere to go but Durand-Ruel, William Tillyer had nowhere to go but Bernard Jacobson. At the time he came into my life I was unaware of how his ’60s had differed from mine. For him it was a decade of struggle and slow self-making, while his contemporaries like David Hockney, Peter Blake, Allen Jones, Richard Smith, and Robyn Denny had constant exhibitions and instant exposure, at home and abroad. With my low overheads, when I sold a Warhol or a Lichtenstein or a Hockney or a Blake I could afford to take a walk. But these were early days for me too as an art dealer, and for Tillyer as a professional artist, each of us making a small income from the etchings we printed.

William Tillyer, Esk 3 – Relentless, An English Idyll (2017–18). Courtesy of Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

An artist needs a dealer, a dealer needs an artist. I believed I had found my homegrown moment in William Tillyer. But greatness does not come from timing alone. It comes from the artist having a sustained vision and the strength of character to see the job through.

William Tillyer did two things in the mid-’50s to suggest these qualities. The first was a painting of a deserted beach in North Yorkshire, entitled Beach and Sea Seaton Carew, dated 1956, the year of Jackson Pollock’s death—dates are always significant—where he was born and grew up and remained until he left for London to go to the Slade School of Fine Art. A small canvas, it is a Romantic vision of sea and land, as desolate as Caspar David Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea. Heinrich von Kleist said that the experience of seeing it ‘was as if one’s eyelids had been cut away,’ a place unpeopled for the rest of human time. It is the landscape of an only child. But the seashore is there. What has disappeared is the monk.

William Tillyer, Esk 6 – Relentless, An English Idyll (2017–18). Courtesy of Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

The second hint he gave was more strident and assertive. A new William Tillyer was born with his first ever catalogue note, written for the final year exhibition at his local art school, Middlesbrough, in 1958, before he left for London. It is a brief text, which spells out, quietly but defiantly, what would obsess him for the rest of his career, an adolescent insight into what he would do with his life:

The program it announces is both hugely ambitious and systematic, even pedantic: “up to a cloud, and back to the pebble.”

—The above is an excerpt from the book The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (2018) by Bernard Jacobson.

William Tillyer, Large Blue Vase with Arranngement after a Painting by Jan Davidszoon de Heem 1606-1684 (2018). Courtesy of Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

“William Tillyer: The Golden Striker and Esk Paintings” is on view through November 24, 2018 at Bernard Jacobson Gallery in London.