Rediscovering Winfred Gaul’s Bold Shapes and Colors, 90 Years After His Birth

Katie White

German artist Winfred Gaul was among the pioneering artists of Art informel, an abstract movement that originated in Germany and spread to France and throughout Europe in the postwar era. Despite the importance of his legacy, the artist himself has remained relatively obscure—even within his native country.

Coinciding with the 90th anniversary of the artist’s birth, a new exhibition, “Winfred Gaul zum 90” (Winfred Gaul at 90), at Galerie Ludorff is seeking to change that.

Winfred Gaul, Gizeh IX (1971). Courtesy of Galerie Ludorff © Achim Kukulies.

The exhibition (fittingly in the artist’s home city of Düsseldorf) takes as its focus Gaul’s “Verkehrszeichen & Signale” (Traffic Signs and Signals) series of brightly hued and geometric canvases, which made up almost the entirety of his practice for nearly two decades, as well as a selection of works from his subsequent “Markierungen” (Markings) series. These are not, however, the works for which Gaul first gained acclaim.

Born in 1928, Gaul began his artistic career as an apprentice to a sculptor before heading to study at the University of Cologne, and then in Stuttgart under the Miro-esque painter Willi Baumeister. In 1953 he headed to Paris and acquainted himself with the critics Pierre Restany (the man who coined the term Nouveau Réalisme), and Julien Alvard, both of whom helped shape Gaul’s understanding of abstraction and the need for a new art language in the postwar era.

Installation view “Winfred Gaul zum 90,” 2019. Courtesy of Gallerie Ludorff © Achim Kukulies.

Having returned to Düsseldorf in the mid-1950s, Gaul became close to the artist Peter Brüning, with whom he would go on to collaborate. Soon, his artistic circle would expand to include the artists Karl Otto Götz, Bernard Schultze, and Heinz Kreutz. With some of these artists, Gaul would come to form Gruppe 53, the group that would ultimately pioneer the subversive and subjective Art informel style that served as a counterpoint to American Abstract Expressionism. During this period, he met with critical recognition, and his works were purchased by major institutions. In 1962 he traveled to New York at the invitation of none other than Clement Greenberg.

Winfred Gaul, Ohne Titel (1960–1970). Courtesy of Galerie Ludorff © Achim Kukulies.

What is striking about Gaul’s career, and what this exhibition makes clear, is how entirely he left the Art informel style behind, and how wholeheartedly he adopted an analytic, color-driven approach to painting in the early 1960s—a move that caused dismay among many of his supporters.

“It is remarkable that Gaul was so well known for his informel painting in the 1950s, but then there was a rupture in his style. He had started his traffic sign works just before his travels to New York, but the trip certainly seemed to strengthen his change in direction. He totally broke with informel and continued with analytical painting,” said Laura-Mareen Janssen of Galerie Ludorff. Perhaps becoming aware, like Mondrian, of the incessant energy and haphazard traffic of Manhattan’s streets, Gaul began to picture these icons of the urban environment in new colors and orientations.

Winfred Gaul, A35 (1972). Courtesy of Galerie Ludorff © Achim Kukulies.

Indeed, it is his playful sensibility that creates a sense of freedom in the works, as his shapes—which have come to be synonymous with the rules of movement—are decoupled and liberated through color and orientation. In works such as Gizeh IX (1971), a triangle shape so common to German street signs is pictured in pale blues and yellows.

The canvases certainly call to mind the practices of American Color Field artists such as Kenneth Noland and Ellsworth Kelly, who also were experimenting with the power of immersive color during these same years. In the exhibition catalogue, art historian Klaus Honnef writes: “Undoubtedly, color was the domain of the artist Winfred Gaul. He had a particularly pronounced relationship to color. He did not even treat the line as a demarcation, or as a separation. Rather, it was a carrier of color to him.”

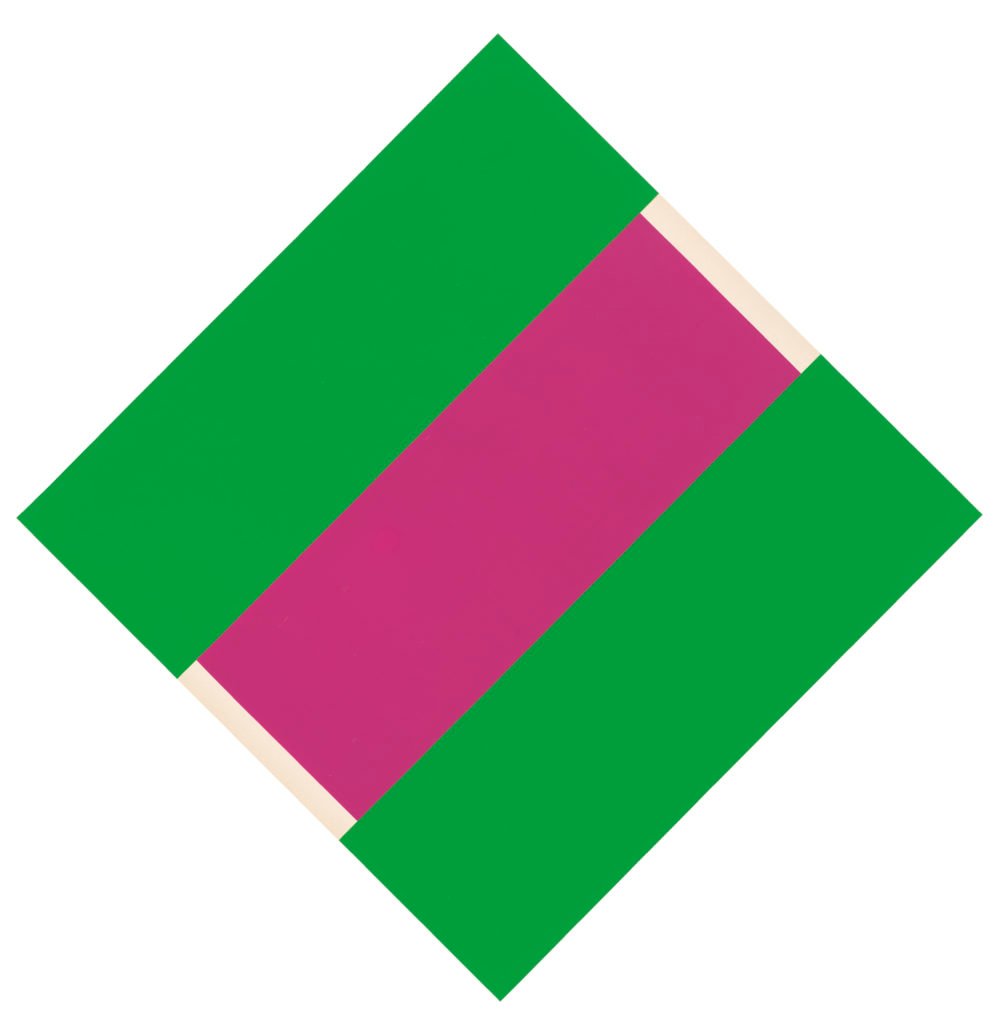

Winfred Gaul, A33, 4 gleiche Felder Diagonal im Quadrat (1972). Courtesy of Galerie Ludorff © Achim Kukulies.

Interestingly, Gaul referred to these works as “totems” and, on an occasion, he brought his paintings to the street to display them alongside actual street signs. In this way, he seemed to call attention to the visual language to which a society or culture has, almost unconsciously, assigned a collective meaning or value. In one sense, he subverted these signs, but in another sense, he elevated them, freeing the shapes to assume new meanings.

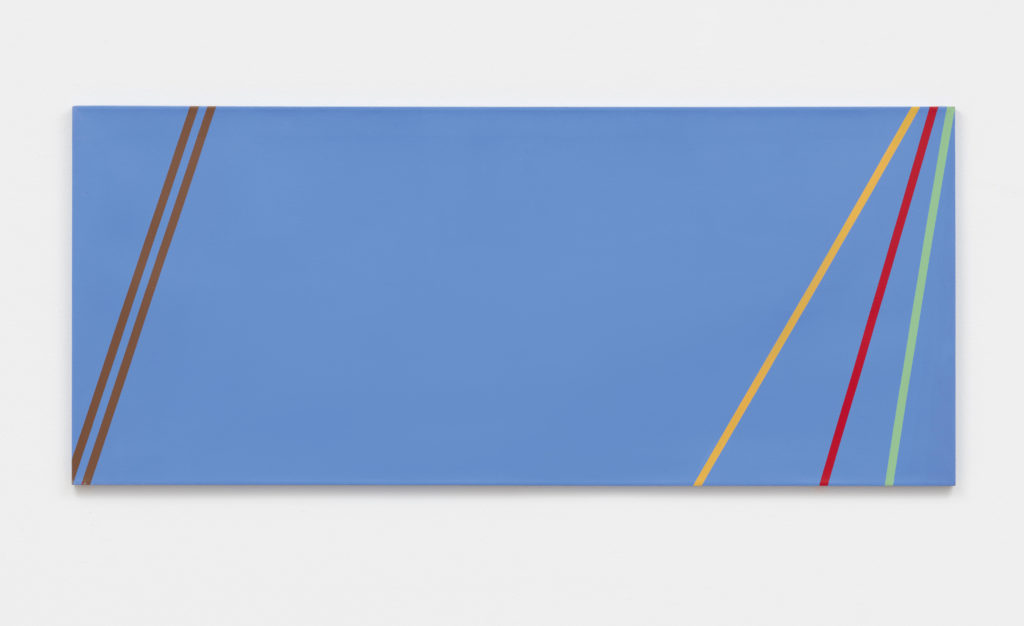

It was a long-term project; Gaul would work with the series into the 1970s, after which he began his “Markierungen” series, a selection of these works are also on view (including F6, Expander IV (1970), pictured below). These are notable for their finer lines and reduction in forms. During these years, Gaul participated in documenta 6 (1977) and was the subject of several major museum exhibitions throughout the 1970s and early 1980s.

Gaul died in 2003. More than 15 years after his death, the exhibition seems strikingly contemporary and—amid a number of exhibitions aimed at elevating overlooked artists of the past—focuses on a painter deserving of a second look.

Winfred Gaul, F6, Expander IV (1970). Courtesy of Galerie Ludorff.

“Winfred Gaul zum 90” is on view at Galerie Ludorff through May 17, 2019.