Art & Exhibitions

Hunter Barnes Documents Serpent Handlers and Gang Members in Deeply Personal Photos

Taking the back roads has led Hunter Barnes to capture some stunning portraits.

Taking the back roads has led Hunter Barnes to capture some stunning portraits.

Sarah Cascone

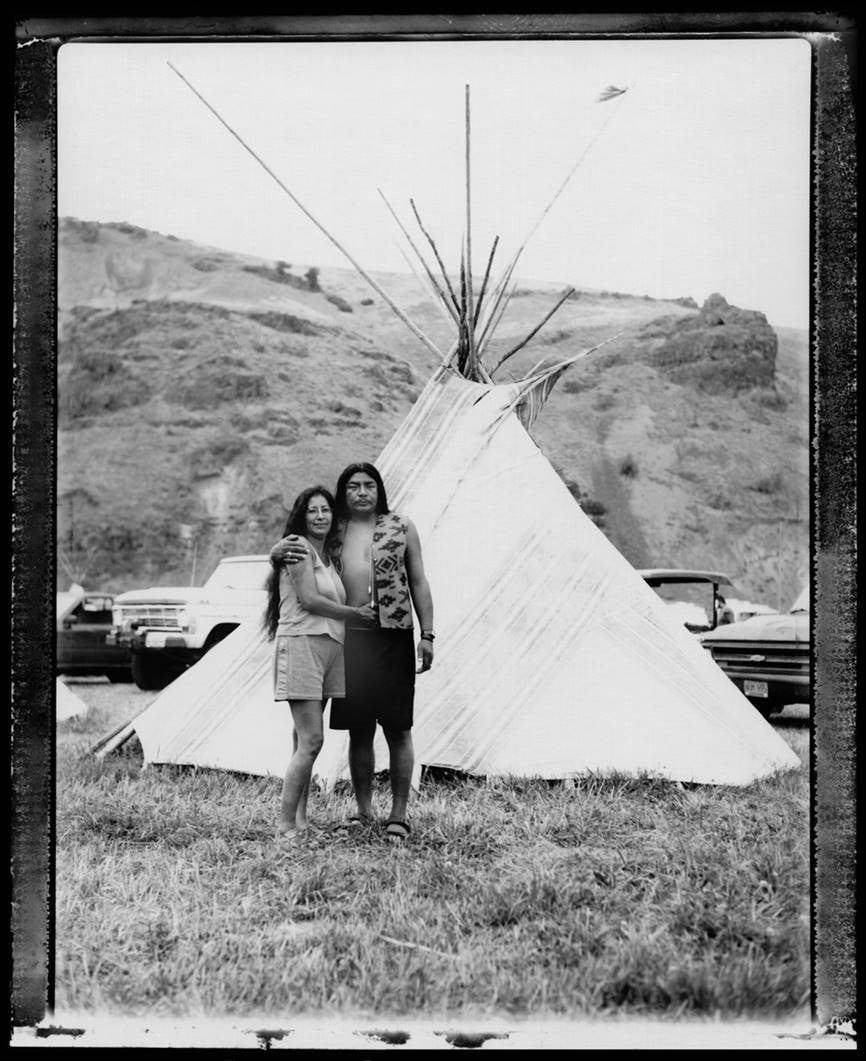

Hunter Barnes, Jason and Delina, from Roadbook.

Photo: Courtesy of Hunter Barnes via Milk.

Documentary photographer Hunter Barnes‘s work introduces him to groups of people that most Americans completely overlook: a small Christian sect that worships with poisonous snakes, the inner city Blood gang members, and the low rider car clubs of the New Mexican desert, just to name a few.

These disparate subjects come together in his upcoming book, Roadbook, which offers a fascinating glimpse into a number of obscure American subcultures.

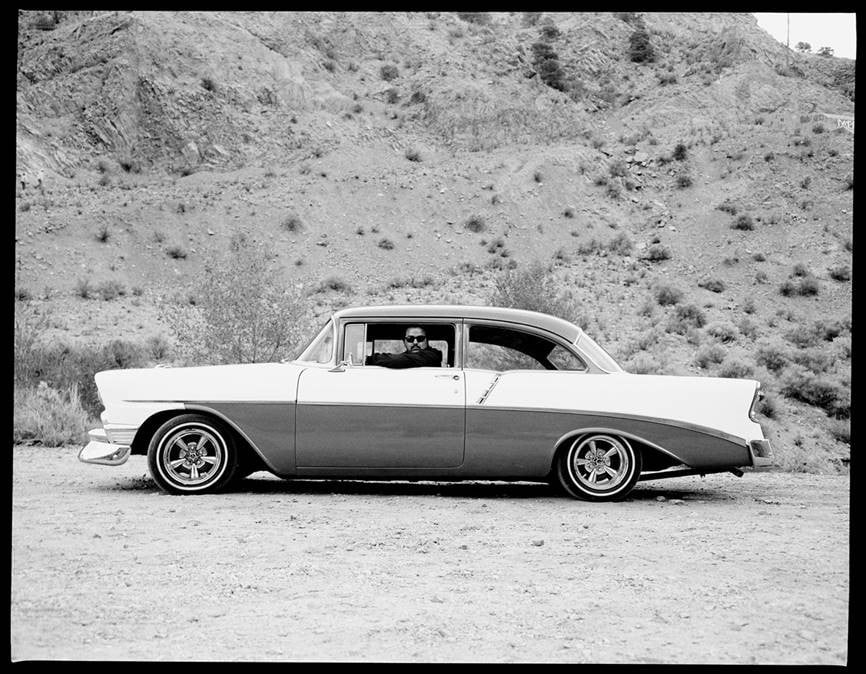

Hunter Barnes, Leroy, from Roadbook.

Photo: Courtesy of Hunter Barnes via Milk.

Barnes, who keeps a studio in Oregon and an apartment in New York with his wife, has spent much of the last 15 years travelling the country, capturing what he calls the “cross sections of America.”

This past month, the new Edition Hotel, which has already played host to some star-studded art world parties, held a one-night only exhibition of photos from Roadbook, hosted by actor Dylan McDermott.

Hunter Barnes with his work at the Edition hotel in New York.

Photo: Courtesy of Aria Isadora via BFA.

Most of the images, taken across the US, have never before been published. artnet News spoke with Barnes about the photos he’s taken and the people he’s met over the course of his journeys.

“I’m really fascinated by back roads in America,” admitted Barnes. That wanderlust has proven quite fruitful for his photographs.

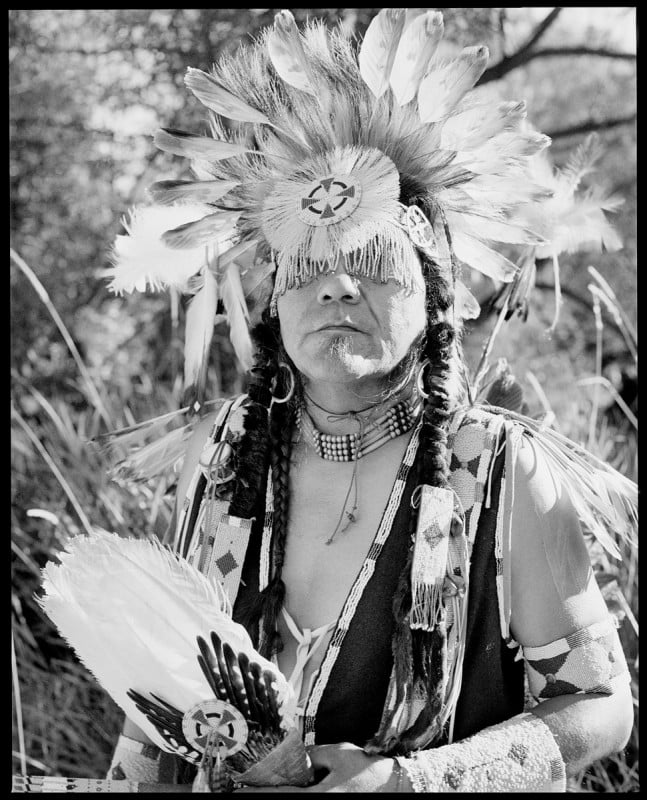

Hunter Barnes, Dreamer, from Roadbook.

Photo: Courtesy of Hunter Barnes via Milk.

On a Lapwai Idaho Native American reservation, for instance, Barnes spent his time with the Dreamers, a very traditional and spiritual part of the Nez Perce tribe that still uses sweat lodges. (The rest of the reservation, says Barnes, is more engaged with the modern age.)

“They set up a tepee for me and I sweat with them for four months before I took any photos,” he noted. Becoming friends with his subjects, and giving them copies of their portraits, is key to his process.

Hunter Barnes, Patrick, from Roadbook.

Photo: Courtesy of Hunter Barnes via Milk.

That personal connection is what makes it possible for Barnes to take intimate, personal snapshots of intimidating characters like Patrick, who hangs with the low riders in Espinola, New Mexico. “People gotta trust me to come into their lives, and it’s up to me to treat them with respect,” Barnes added.

“He’s one of the few photographers who lives with his subjects before photographing them,” said McDermott admiringly. “He really develops relationships.” The actor is a photographer himself, but a busy film and television career doesn’t give him the luxury of time to prepare for a photo series that Barnes has.

Hunter Barnes, CA State Game, from Roadbook.

Photo: Courtesy of Hunter Barnes via Milk.

One exception to this rule are the photos Barnes took of prisoners at a maximum security jail in California, the name of which he cannot disclose. Nevertheless, thanks to gang connections Barnes made during his travels, he had friends who spread the word of his impending arrival, and the inmates were open, perhaps surprisingly so, to posing for him.

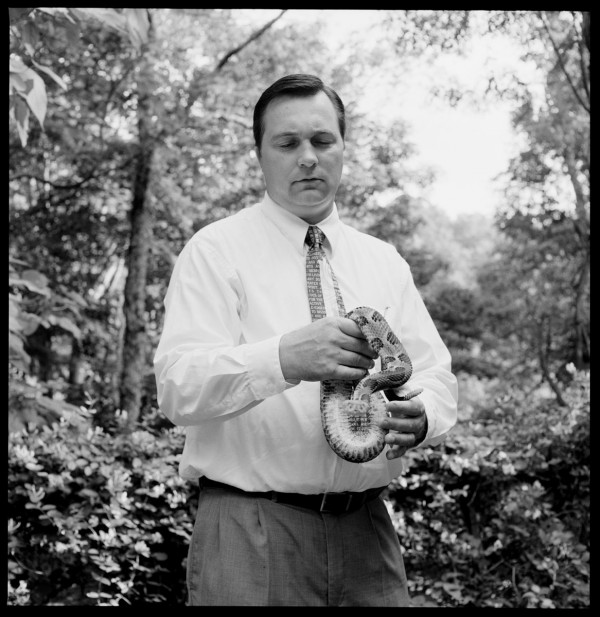

A friend also introduced Barnes to the serpent handlers, a small Christian church in West Virginia, the only state where it is legal to incorporate venomous snakes into religious services.

Hunter Barnes, A Prayer for God’s Will, from Roadbook.

Photo: Courtesy Hunter Barnes via Milk.

One thing he learned right away is how much the group values the distinction between snakes and serpents. “My friend Snook told me ‘Honey, anyone can pick up a snake—handling a serpent is venomous!'” Barnes told us.

The practice is taken from a verse from the King James bible, Mark 16:18, which begins “they shall take up serpents.” In a literal interpretation of that passage, the serpent handlers catch timber rattlesnakes before each service, and release them back into the wild afterward.

While Barnes didn’t witness any snake bites during his time at the church, the practice of serpent handling is undoubtedly deadly: the pastor, Randy, “a dear friend,” died from one about a year after Barnes’s visit.

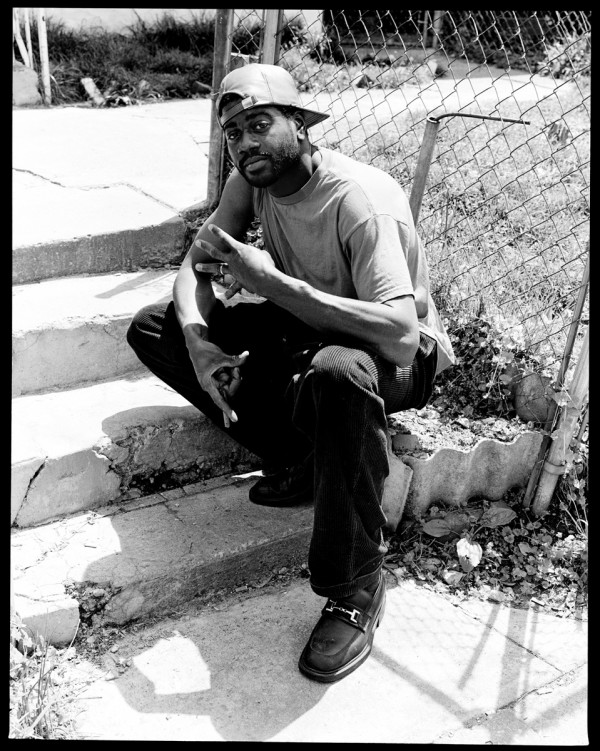

Hunter Barnes, One Boss, from Roadbook.

Photo: Courtesy of Hunter Barnes via Milk.

Other photos capture a more fleeting connection. One particularly haunting image captures an world-weary seeming black man with a pained look in his eyes. Barnes encountered him on the streets of Portland one day, but “I didn’t feel comfortable asking to take his photo.”

Shortly afterward, while Barnes was sitting on his friend’s front porch with a pitcher of water, the man happened by, and asked for a glass of water.

Hunter Barnes, M.A.C., from Roadbook.

Photo: Courtesy of Hunter Barnes via Milk.

“He was having a bad day, I could tell, that day,” Barnes recalled. He never got the stranger’s name, but he did get the photo, snapped on a 195 Land Camera with 66/5 Polaroid film. “I gave him the Polaroid and I kept the negative.”

Hunter Barnes, Matthew, from Roadbook.

Photo: Courtesy of Hunter Barnes via Milk.

Roadbook, by Hunter Barnes, will be published October 31, 2015.