People

artnet Asks: The Young Artist Making Michelangelo-Level Drawings

The artist Ian Ingram talks about the last five years.

The artist Ian Ingram talks about the last five years.

Artnet News

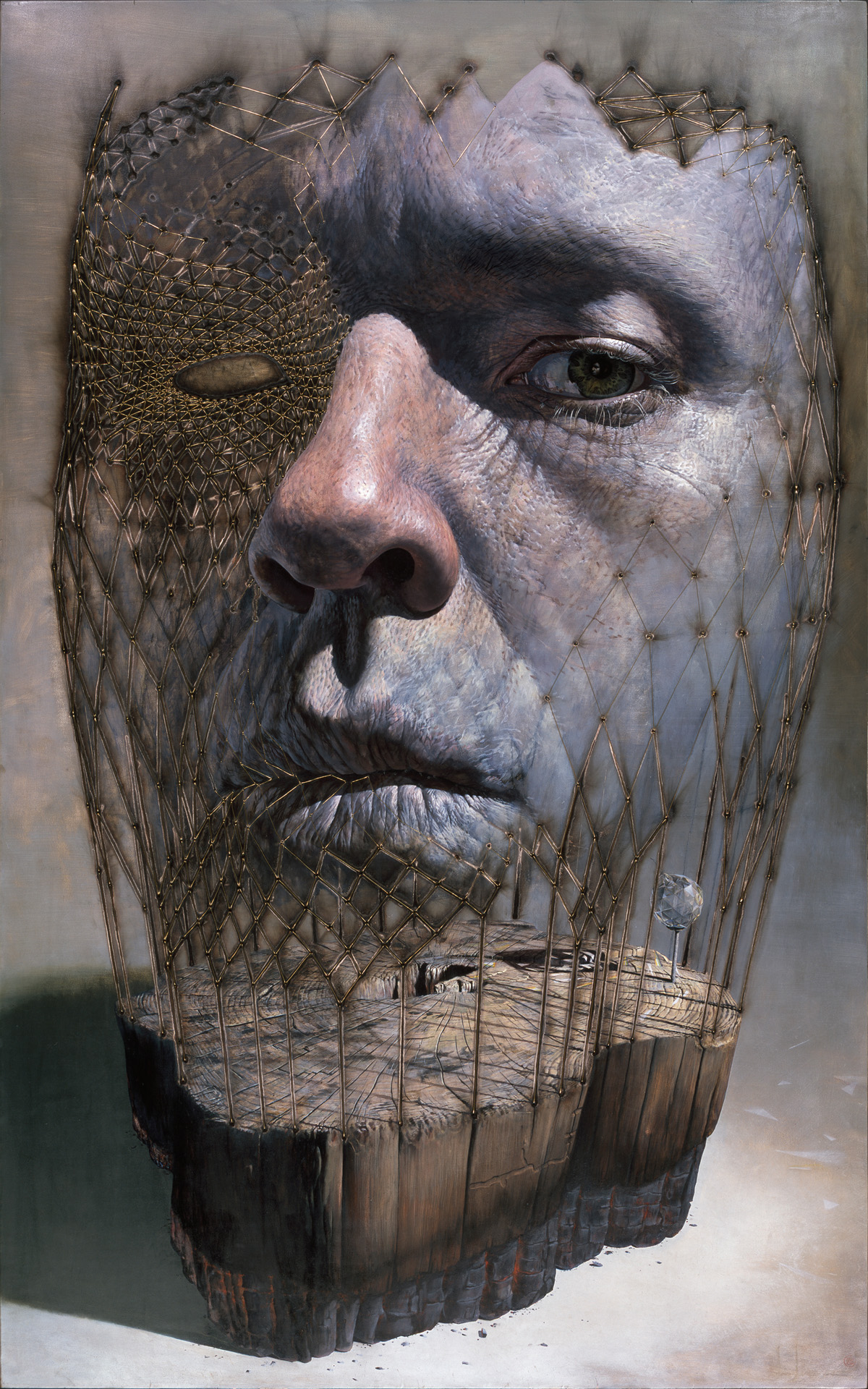

Ian Ingram creates portraits that are larger than life, in more ways than one. Daunting in scale and even more daunting in their carefully observed and masterfully rendered attention to detail, his drawings and paintings confront the visible world with unflinching eye. His latest exhibition, “Ash and Oil,” offers a survey of the last several years of his work, and is currently on view at 101/EXHIBIT in Los Angeles through Saturday. Don’t miss the chance to see these monuments to self-portraiture in person.

In this quick Q&A, Ingram offers insight into his process, especially how hard starting a painting can be.

Ian Ingram at the opening reception for “Ash and Oil”. Photographed by Stefania Rosini. Works from left to right: Inseparable Thieves (2013); Of Salt and Faith (2013), To Burgle or Borrow (2013)

Can you describe the process of creating your self-portraits?

One: Open eyes. Two: Gaze in wide wonder at the miracle of life. Three: Panic at the inability to communicate the miraculous. Four: Suck it up, deal with the inevitable failure of such an enterprise as capturing a miracle, and start making marks on a canvas. Five: Work work work, look look look. Cry, destroy, work work work, look look look. Repeat approximately seven to eight times until an organic sprout of new life starts peeking out. Nurture that shoot and let it become its own thing. Six: Sell it to buy fertilizer.

Describe the journey that led you to be an artist.

“Journey” implies a starting point and a destination, both of which feel elusive in the way I define myself as an artist. For the sake of brevity, however, I will pick drawing during story time as a starting point. Pencil and paper, and Roald Dahl tickling the dimensions of imagination. Drawing has remained a key to a sacred interior space that offers escape and an eternal welcome. Making art always FELT good, and combine that with attentive parental support and I was slowly able to grow into my definition of an artist.

When it was time to leave home, I recall my mother saying, “What about art school? Your tests would be art, your homework would be art, and your teachers would be artists.” To this I answered, “No way. That’s too good to be true.” “Um, no,” she said, “That’s one way to become an artist.” I signed up. This got me to the next starting point, which, for the sake of this interview, we will call the destination.

Ian Ingram, Each Other (2014). Courtesy of 101/EXHIBIT.

What is a typical day in the studio for you?

Walk in, close the door, shut the windows, turn off the Internet, look in the mirror, try to turn off the mind and let the eyes get to seeing. Follow the eyes, and be gentle with the failings of the mind. Become hypnotized by the patterns of cellular life and boggled at the existence of life. Try to paint that. Fail.

Tell us about your current show “Ash and Oil” at 101/Exhibit.

This show is the last five years of my work and includes my shift from a decade of focusing on charcoal and pastel drawing, ash, to the last year of painting, oil.

What feature of the human body do you think is the most difficult to draw?

Genitalia. So much psychological baggage in staring at our “original sin.”

“Ash and Oil” installation view. Photographed by Stefania Rosini.

How much value do you think young artists should place on social media?

As much as they want to. If it brings you alive, go all in. If it’s a burden, turn it off.

What is the best museum/gallery show that you’ve seen recently?

The Antonio Lopez Garcia retrospective at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

If you could own one work of art, which one would it be and why?

I’d take La Capella Sistina. I would put a huge bed right beneath the most potent negative space in Western art history, that magic void between the out stretched fingers of God and Adam. Because why not?