Reviews

David Ebony Interviews Artist and Editor Walter Robinson on His Parallel Lives

Robinson created “Spin Paintings" a decade before Damien Hirst.

Robinson created “Spin Paintings" a decade before Damien Hirst.

David Ebony

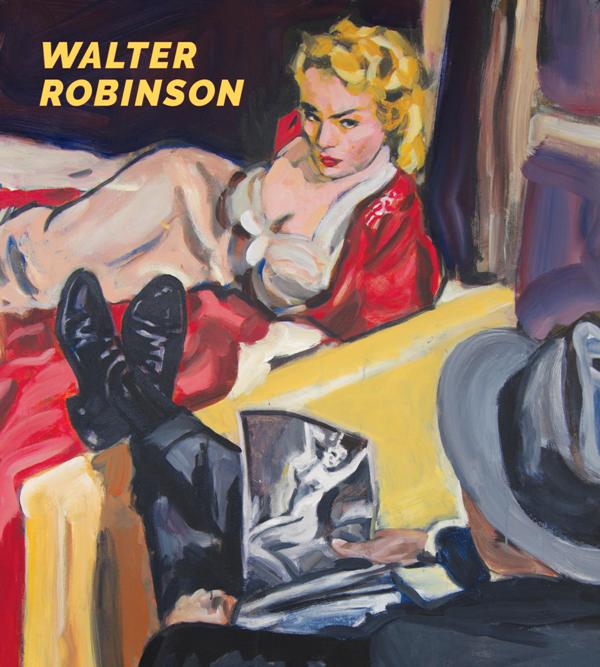

A new monograph on Walter Robinson’s paintings,

published by University Galleries of Illinois State University, 2015.

All images this article courtesy University Galleries, Illinois State University.

While he was a vital chronicler of the New York art scene for over four decades, Walter Robinson all the while continued to paint. Who knew? A recently published monograph, Walter Robinson, is a lively testament to his parallel career. Artist and writer, Robinson is a true Renaissance man (if there is such a thing these days). He pioneered online contemporary art coverage and is also a performer of sorts, having co-hosted, along with Paul H-O and Cathy Lebowitz, Gallery Beat, a seminal cable TV show of the 1990s focused on contemporary art.

Born in Wilmington, Delaware, in 1950, and raised in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Robinson moved to New York City in 1968, where he studied art history and psychology at Columbia University. He co-founded the contemporary art journal Art-Rite in 1973, and in 1978 became a contributing editor and the news chief at Art in America magazine. In 1996, he founded Artnet Magazine, and generated these news pages for the following sixteen years.

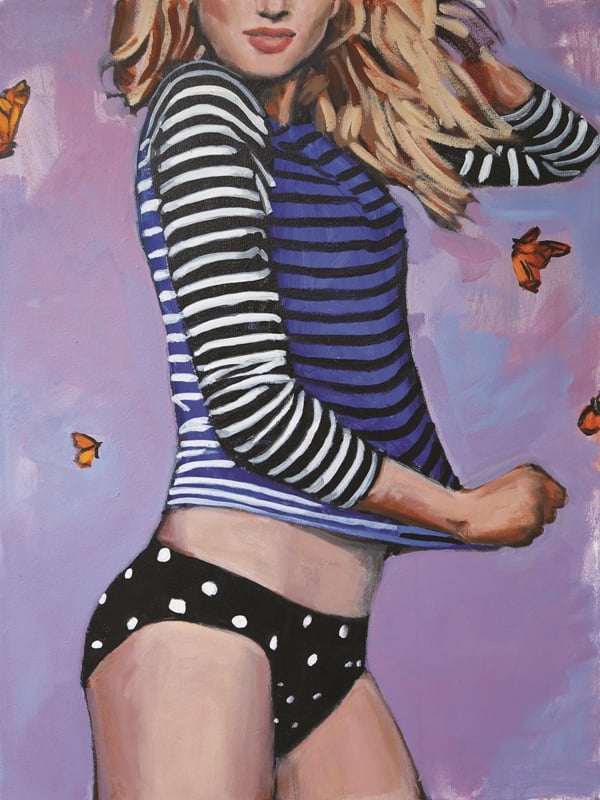

Walter Robinson, Sun, Surf, and Style: the Swim Tee, Ride the Wave (2014).

Image: Courtesy of the artist and University Galleries, Illinois State University.

A longtime friend and colleague, Robinson brought my Top 10 column to Artnet soon after the site launched, and when he left his Art in America post, associate editor Stephanie Cash and I tried to fill his formidable boots as co-editors of the magazine’s news pages. In his writing, Robinson has developed a distinctive voice full of humor and sometimes biting sarcasm. His commentary is often irreverent yet always illuminating—not an easy trick to sustain.

Though better known as a writer, Robinson regularly and frequently showed his paintings over the years, beginning in the East Village in the early 1980s. He produced colorful, photo-based, Pop-inflected paintings inspired by pulp fiction book covers, sexy lingerie ads, and consumer product advertising. He also created abstract works, sometimes using mechanical processes, as in a 1980s series of “Spin Paintings,” which predate by over a decade Damien Hirst’s similar-looking efforts.

Walter Robinson, Ugly Trap (1986).

Image: Courtesy of the artist and University Galleries, Illinois State University.

Robinson’s art work appeared in some notable galleries, such as Metro Pictures, and most recently at Lynch Tham in New York. But his first museum survey was held just last year. “Walter Robinson: Paintings and Other Indulgences,” was organized by Barry Blinderman, director of the University Galleries of Illinois State University in Normal, Illinois, where the show debuted. It travels to the Galleries at Moore College of Art & Design in Philadelphia, January 23-March 12, 2016.

The exhibition’s accompanying book, Walter Robinson, contains some 100 color reproductions, a detailed biographical time-line, plus essays by Blinderman, Vanessa Meikle Schulman, Charles F. Stuckey, and Glenn O’Brien. In a recent interview via phone and email, Robinson shared with me his feelings about this important milestone in his career, as well as some thoughts about the state of art today.

David Ebony: I’m looking forward to seeing your show when it comes to Philadelphia. But even if one can’t get there, I’m sure this book will help solidify your reputation as a painter. How did the project evolve? How well do you think it represents your career to date?

Walter Robinson: The book and the show were all Barry Blinderman’s doing. He’s been amazing. I showed with his Soho gallery, Semaphore, in the 80s; and ever since he took the job as director of the Illinois State University galleries in Normal, in 1987, he has done monographic shows of most of the artists he worked with in New York—Donald Baechler, Jane Dickson, Keith Haring, Duncan Hannah, David Wojnarowicz, Martin Wong. It’s a long and illustrious list. I let everyone else go first! This show has 92 paintings in it, and the book has still more, so it’s fairly comprehensive.

Can you briefly say how the New York art world has changed since you first arrived on the scene in the mid 1970s?

So much has happened! The art world is larger, and richer, of course, and we have new art movements. But most interesting I think is the increasing predominance of the market model. There are so many different styles of art, and they all find buyers. We’ve had this circular, almost random “pluralism” for the last several decades. Laura Hoptman’s “Forever Now” show, last winter at MoMA, was all over that idea—the essential randomness of art today—but nobody really got it.

You seem to be an equally prolific writer and painter. Both disciplines require a tremendous amount of focus and time. How do you switch gears back and forth, or how do you reconcile the two?

Certainly we have more prolific critics! But I did a lot of editing at Artnet Magazine. As an artist, you focus on one thing: yourself. As a writer you can lay claim to everything and anything. At this point in my life I much prefer facing an easel to sitting in front of a keyboard. But I can look back at all my editorial work as an indispensable course in thinking.

You coined the term “Zombie Formalism” to describe recent works by certain abstract painters. You intended it as a put-down, I think, but it has taken hold, and I hear it mentioned all the time—often in a rather positive way. What are your thoughts about that?

It was only a little joke, and not meant negatively at all. But it did catch on, thanks largely to its use by other writers, notably Jerry Saltz and Roberta Smith. I was describing a kind of popular new abstraction that emphasized process and metaphor, but the term quickly degenerated into an all-purpose pejorative. What does it mean now? Art that is shallow, decorative, meretricious. It’s happened to me before, actually. Back in the ’80s, I billed the East Village art scene as a secret art collective disguised as 50 storefront galleries; but the real art world decided that the EV stood for everything bad about art. Oh, did I tell you that I suggested we call the West Chelsea art scene by the name WeChe? That didn’t catch on.

Walter Robinson, Amboy Dukes (1981).

Image: Courtesy of the artist and University Galleries, Illinois State University.

What do you look for in an image for your own work, a subject for your painting? What is it about the image that attracts you?

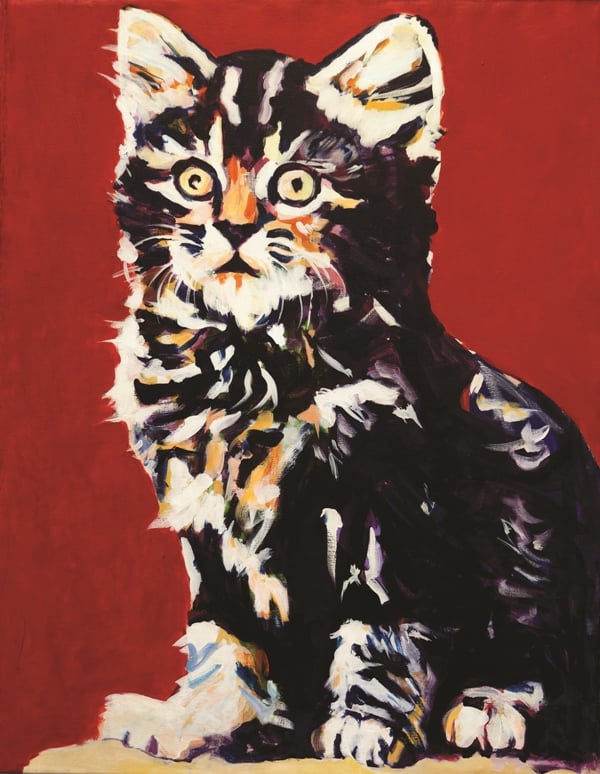

It’s always about desire! When I was younger, it was romance. Now it’s cheeseburgers! I like images that enlist the viewer in a real subject-object dynamic. It’s like pictures of kittens; the animal has evolved to appeal to us on an atavistic level. So my pictures of cake, the pharmaceuticals, the Normcore fashion models, those are all images that are specifically designed to sell. It’s direct address—like Barbara Kruger, actually.

Walter Robinson, Untitled (Red Kitty) (1982).

Image: Courtesy of the artist and University Galleries, Illinois State University.

What painters works do you look at the most? Who are some of your favorites? You mentioned Kuniyoshi the other day at the Frank Stella opening.

I like so much art. The problem isn’t that we have too little good art, but that we have too much of it. Most recently, I was snowed by what I saw at the studio of the painter Kate Shepherd, who shows at Galerie Lelong. She’s much better than Frank Stella!

What keeps you excited and interested—or at least engaged—in the art world after all these years?

I’m an addict! You know, in kindergarten I was the kid who could draw. I specialized in high-noon showdowns, with the sheriff wearing a silver star and the outlaw a black bandana. But I liked to put both items of “flair” on both figures. If I had those drawings now I could show them!

Walter Robinson with Duncan Hannah’s painting of Robinson, Dimming the Day (1983).

Image: Gregg Smith, 1984.

David Ebony is a contributing editor of Art in America and a longtime contributor to artnet.