Opinion

Why the Confederate Flag Should Not Be Placed in an American Museum

The history of the Confederate Museum movement offers lessons for activists.

The history of the Confederate Museum movement offers lessons for activists.

Ben Davis

On Saturday, activist Brittany “Bree” Newsome scaled the flagpole at the South Carolina state capital, taking down the Confederate battle flag that flew there herself, to honor the nine victims of Dylann Storm Roof’s white-supremacist terrorist attack.

“We removed the flag today because we can’t wait any longer,” Newsome said. “We can’t continue like this another day.”

She was arrested, and #FreeBree trended on Twitter.

Mainstream conversation has converged on a rather more genteel approach to this symbol: “Put it in a museum.” From Barack Obama to Rand Paul, this has become the mantra.

With change in the air and all the symbols of the Confederacy under new scrutiny, perhaps we should ask the question of what “putting it in a museum” really means. For “museums, and the museumizing imagination, are both profoundly political,” as Benedict Anderson wrote in his landmark book, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism.

We should ask: What does it mean to “put it in a museum” when Roof was, from what we know from his own website, a museum nut? Where the Confederate past was mythologized, venerated, and museum-ized, he went.

Dylann Storm Roof in front of the Museum and Library of Confederate History in Greenville, South Carolina.

Confronted with the evidence that Roof came to the Museum and Library of Confederate History in Greenville to be inspired, chairman of the institution’s board Terry Rude still stood firm last week against taking the Confederate battle flag down.

“That call is based on the assumption that that’s a racist flag and it’s not,” Rude told a local TV station. “It is a concession that it is a racist symbol, which is a concession to—as far as we’re concerned—a lie.”

We can call this the “Accidental Racist” defense, after the Brad Paisley/LL Cool J anthem, an unintentional bit of comedy that declared that the Confederate battle flag was just a symbol of being a “Skynyrd fan.”

You’ve probably heard a lot of this too this last week: The Confederate flag is, to its defenders, merely a symbol of “Southern pride.” Or even a more general symbol of rebellion.

This mystified idea of Confederate symbolism is not just some mistake. It is the product of a deliberate attempt at whitewashing, reframing, and “vindicating” the history of the South, post-Civil War—a process in which the Confederate museum movement has played a starring role.

In a 2011 article, historian Reiko Hillyer tells the tale of the transformation, in 1896, of what had been Jefferson Davis’s house in Richmond, Virginia into the Confederate Museum. It would set the template for a wave of such institutions, including Charleston’s own Confederate Museum, founded three years later and a site of protest since the murders.

“Relics are records and symbols,” one South Carolinian would write in Confederate Veteran, touting the importance of such institutions. “There is a subtle spirit in these and if we do not…bind it to our uses we will have bread without salt.”

The immediate inspiration of Richmond’s museum was almost comical. In 1888, a group of Chicago entrepreneurs had purchased Libby Prison, a three-story warehouse in the Confederate capital where Union soldiers were confined. Hoping to spin commercial gold from the dark attraction of the former Confederate site, the speculators had the fortress-like structure transported stone by stone to the Midwest.

Unreconstructed Southern nationalists recoiled in horror at Northerners literally taking ownership of history. And so, a group of Richmond women banded together in the 1890s to found their own museum as a counterattack.

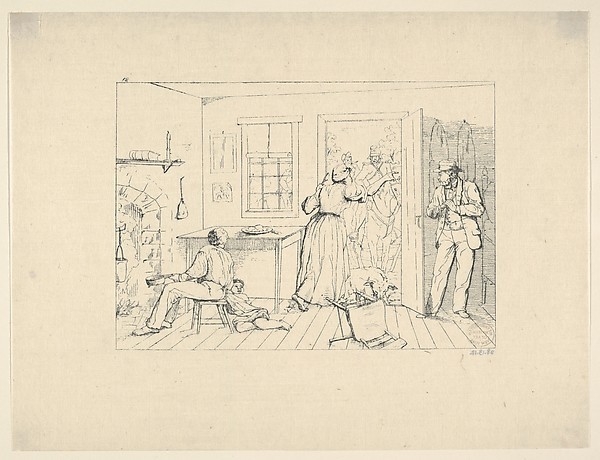

Exhibits included blood-stained handkerchiefs and battered swords, but also manuals on the religious instruction of slaves and even an etching showing a slave concealing her master from Yankee invaders, to prove the point that slavery had been virtuous. The founders of the Confederate Museum declared that its artifacts were to stand as “mute evidences of the righteousness of our cause.”

Adalbert John Volck, Slaves Concealing their Master from a Search Party (from “Confederate War Etchings”) (1861–63).

Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The same year the Confederate Museum opened, Jim Crow became the law of the land in Plessy vs. Ferguson. These were different moments of one process: Southern elites, given a free hand since the disgraceful Compromise of 1877, were now aggressively consolidating their authority.

Yet at the same time, commercial interests pressed against the maintenance of North-South hostility. In this context, downplaying the unresolved aspects of the conflict in favor of a narrative of “brother-against-brother” tragedy had considerable appeal.

The Confederate Museum’s collection became a resource for those looking to understand the Southern point of view. In its first decade, more than half of the visitors to the Richmond institution were Northerners. The doyennes of the Confederate Museum were consulted as experts on “relations between the races” in the South, including for textbooks.

Isobel Bryan, founding mother of the museum, had been a “special pet” of Robert E. Lee as a child. “It is a tremendous task to convert, one by one, all the Yankee nation,” she said. Yet, sure enough, Hillyer writes, “In a reversal of an old axiom, history was written by the losers.”

Thus it was that, even as the children of the freed black slaves who fought with the Union were forced to ride in separate train cars, it was the Southern perspective on the conflict, not the Northern one, that came to dominate the popular culture of the United States.

It is this narrative what shapes D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915), a defining landmark in film history, with its heroic Klan and scheming, predatory blacks. It is what structures the revanchist romance of Gone With the Wind (1939).

Its influence can be felt at least up until Ken Burns’s The Civil War (1990), a pioneering piece of documentary that, for all its strengths, left me as a young man with the overwhelming flavor of the romanticized “brother-against-brother” narrative.

In recent years, the idea of “white supremacy” has experienced a revival as a term of analysis. It has, it seems, two meanings. It conjures, on the one hand, images of men in white hoods, skinheads, and the hateful ideology that seems to have animated Roof. On the other hand, it has a more diffuse meaning, pointing to the way the systems and institutions are set up to guarantee discriminatory outcomes, even in our purportedly “post-racial” society.

The former functions by militant avowal of hate; the latter can function by disavowal, denying that the heritage of racism has to be addressed. (Thus, the Wall Street Journal‘s editorial on Charleston astoundingly takes the moment of the tragedy to explain that Martin Luther King’s dream has been realized and “institutionalized racism” no longer exists.)

I mention this distinction because these two definitions of “white supremacy” also correspond to the two symbolic meanings of something like the Confederate flag. On the one hand, it functions as “America’s swastika,” a badge of racist identity and racial pride. On the other, it can be touted as an innocent symbol of “Southern heritage.”

Yet the latter claim can only make sense by denying what that heritage actually is. And, once you stop to think about it for a second, it actually seeds the ground for the more militant form of white supremacy.

For if you deny that the history of racism still shapes every part of contemporary American life, then you leave only the most corrosive racist stereotypes to explain the inequalities that do still very much exist. Such two-sided logic is on abundant display in Roof’s manifesto, which asserts that the history of white supremacy is mere “historical lies, exaggerations and myths,” only to go on to claim that African-Americans are lower than dogs.

What does this mean about the question at hand? Of course, it is simple enough to argue that saying “put it in a museum” has become so universal so quickly precisely because it is so vague. It matters greatly what kind of museum it is put in.

The fact that the open glorification of Confederate symbols is being reconsidered is no small thing. But let’s be honest: If craven corporations and perfidious politicians have hopped on this bandwagon right now, it is at least in part to score points in this emotional time while having to do as little as possible about the material realities of racism.

Struggles over symbols are always vulnerable to becoming purely symbolic. And so, today, the concrete case of the Confederate Museum might serve as a reminder that the fight has to be over more than just the symbols themselves. It has also to be over control of the institutions that shape and give these symbols their force in the first place.

“It’s time for a new chapter where we are sincere about dismantling white supremacy and building toward true racial justice and equality,” Bree Newsome said, explaining her action on Saturday. Taking her challenge seriously is the key to making sure that “putting the flag in a museum” isn’t just the rallying cry of another half-hearted compromise, but instead stands for having truly consigned the history that it stands for to history.

This needs to be a t-shirt, an album cover, a mural…. #freebree pic.twitter.com/7e6CmTqyNG

— Dave Zirin (@EdgeofSports) June 27, 2015