Photo: courtesy Richard Nagy Ltd.

Amah-Rose Abrams

Wilhelm Heinrich Otto Dix was an Expressionist master shaped by the harrowing experience of war. He lived through and fought in both world wars, and vividly relayed the horrors of both front-line battle and post-war society through his work.

Born in 1891 in the town of Untermhaus in Germany, Dix’s first experience of making art was in the studio of his cousin, Fritz Amann, who was a landscape artist. Dix became his apprentice, and when young artist showed promise, his family suggested that he take on a further apprenticeship, with landscape painter Carl Senff.

His talent already evident to his mentors, Dix went on to attend the Kunstgewerbeschule art school in Dresden. It was here that he came into contact with art and literature that would later shape his work. The young student was exposed to some of his greatest influences, such as Friedrich Nietzsche, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and printmaker Max Klinger.

When World War I broke out, Dix, aged 23, volunteered for service and fought all over Europe. Exposed to life on the front line, Dix fought in the trenches of the famously devastating Battle of the Somme, and later on the grueling Russian front. In 1918, he was injured and finally discharged. He kept notebooks and sketchbooks throughout the war, recording the experience, which would shape him both as a man and an artist.

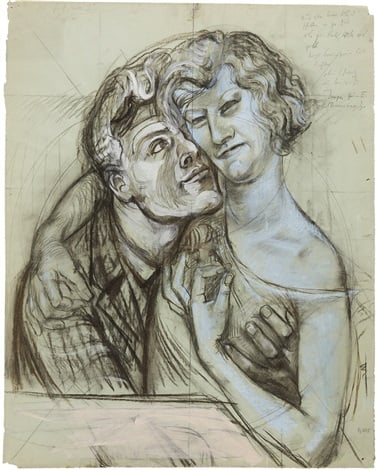

Otto Dix Apotheosis (1919)

Photo: courtesy Galerie St. Etienne

After leaving the army, Dix returned home and, after a period of recuperation, moved to Dresden where he continued his studies at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste. It was there that he met and befriended George Grosz, who, along with Dix, would go on to be a key artist in the Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity movement.

New Objectivity was perceived at the time as being an Americanized way of thinking, where instead of returning to a pre-war philosophy, people adopted a more functional, businesslike attitude. For those artists who adopted this practice, this meant stripping back the veneer of polite society, and exposing the harsh reality of life under the Weimar Republic.

After his wartime experience, Dix’s landscapes went from pastoral to depicting scenes of death and destruction. His personal memories of the front line became the main subject matter of his work, along with satirical depictions of a post-war Germany heading towards WWII.

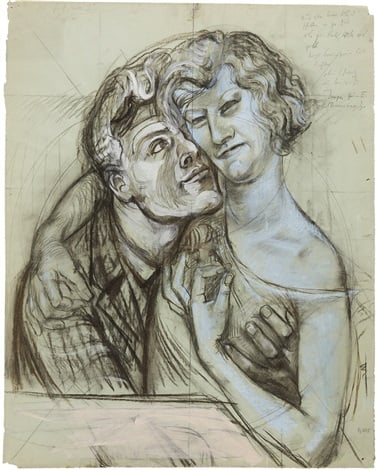

Otto Dix Tavern in Hamburg(1922)

Photo: courtesy Richard Nagy Ltd.

This aspect of his work was exhibited at the De La Warr Pavillion in the South of England in 2014, in the exhibition “Otto Dix: Der Krieg,” for which the British Museum made a rare loan of sketches and drawings.

Dix’s subject matter often comprised of recreated scenes from battle, rotted skulls, broken bodies, and men who had been maimed in the war limping through streets of post-war hedonism. He also painted negative caricatures of the partying masses in the Weimar Republic and strung-out prostitutes.

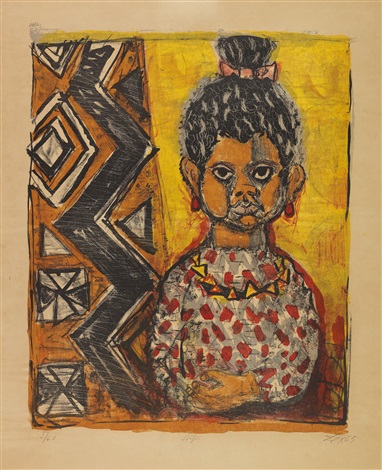

Otto Dix Susu, (ca. 1964–1965)

Photo: courtesy Ketterer Kunst GmbH & Co KG

Dix was very much influenced by the Dada aesthetic, which was growing in popularity. In 1919, the first international Dada Art Fair took place in Berlin. Dadaists John Heartfield and Rudolf Schlitchter hung a pig-faced effigy of a German soldier from the ceiling in direct defiance of the current regime in the wake of their defeat in WWI.

Two of Dix’s best know works are both triptychs, Metropolis (1928) and War (1930). They address, respectively, the post-war changes in German society after WWI and WWII. In commenting on these and other events, Dix’s work serves as a visceral and often cruel record of his time.

“The object is primary, and the form is shaped by the object,” he said in a very rare public statement, published in 1972.

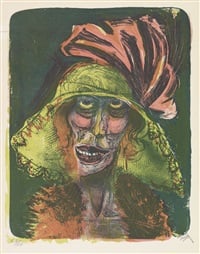

Otto Dix Leonie (1923)

Photo: courtesy Ketterer Kunst GmbH & Co KG

His imagery could be surrealistic, warped, and charicaturesque. His paintings and prints created a narrative of war and the results of war—from violent death and destruction, to the hedonistic lifestyle that came as a reaction from being on the losing side.

In contrast to what one might imagine, Dix was apparently quite the “dandy,” and a fantastic dancer.

“All of the delicacies and liqueurs I could muster were there to greet him,” wrote art dealer Johanna Ey on meeting Dix, in her memoirs. “He soon arrived with a flapping cape, large hat, and greeted me with a kiss on the hand, something very unusual for me in those days. In the morning he unpacked his box, revealing: patent leather shoes, perfumes, nothing but beauty care items…”

In 1937, Dix was included in the Degenerate Art exhibition organized by the Nazis in Munich. Artwork was defined as degenerate for supposedly being Communist, un-German, or Jewish. Dada was particularly disliked, and all the works included were later burned. Dix was sacked from his post at the Dresden Academy. As with all artists under Nazism, he was forced to join the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts, and ordered to paint only decorative landscapes—although he sometimes still managed to create works which criticized the regime.

WWII saw Dix return to the front line, and when the Nazis were defeated in 1945, he was freed of his “degenerate” status. His career and reputation resumed, and he lived out the rest of his days in Singen, Germany, where he died in 1969 aged 77.

Dix’s allegorical aesthetic has influenced many artists—including Jim Shaw, demonstrated in his recent New Museum retrospective, “The End Is Near“—but more so than that, it is the legacy of truth he left behind that he is best remembered for. He and the other war poets and artists of his generation left an indelible mark on the history of Europe, one that we can look back on in horror, empathy, or both.