As most of the world shuts down and many millions of people find themselves isolated at home, perhaps it’s fitting that a new (though now closed) exhibition at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art delves into the work of a woman who lived very much off the grid, and according to her own psychic rules.

“Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist” is a sprawling look at the paintings to which Pelton dedicated her life—they were based largely on themes of mysticism and theosophy and informed by her own visions. In the few days before it closed as a result of the health crisis, the Pelton show—which was originally organized by the Phoenix Art Museum’s Gilbert Vicario—was already earning accolades. And it is part of a wider trend of historians reappraising female artists inspired by the occult (Hilma af Klimt, anyone?).

Whitney Museum curator Barbara Haskell, who worked on the New York presentation of the show, recently spoke with Andrew Goldstein to discuss the artist’s stranger-than-fiction life story and why her work is hitting a nerve right now.

Curator Barbara Haskell. Photo: Scott Rudd. Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

How did you first come to learn of Agnes Pelton and her work?

In the late 1990s, I was introduced to it by a dealer in Los Angeles and I fell in love with the work. The trajectory of how the Whitney ended up getting its first Agnes Pelton painting in 1995—it’s interesting, because she was totally unknown. So I presented her work to the acquisition committee and they turned it down.

But I thought that this was something worth pursuing. And I came back to them a second year and they also turned it down. I came back to a third year, and finally, Leonard Lauder, who was at that point chairing the committee, said, “You know, Barbara believes in this work. I do not want her to come back a third year. Let’s buy.” So two [Pelton] works have been in the museum’s collection for over 20 years, and they have been on almost continuous view in the new buildings since we opened in 2015.

A portrait of Agnes Pelton. Photo: Alice Boughton.

It’s often helpful to know about an artist’s life when looking at their work, and for Pelton, this may be especially critical as she had a particularly dramatic upbringing, like something out of Dickens.

As she said herself, it was a scandal that cramped both her mother’s life and her own life, and it does figure very importantly in her decision to seek a different meaning in life, away from the physical and into something more spiritual.

So it happened to her maternal grandparents; Theodore and Elizabeth Tilton. Theodore was an important newspaper editor who was the protégé of the very well-known abolitionist and pastor Henry Ward Beecher. At one point, Elizabeth began an affair with Ward Beecher, who of course in his sermons was preaching celibacy and morality, and when the affair was made public, Theodore sued Ward Beecher for alienation of affection. Elizabeth refused to testify against Ward Beecher, who was still her pastor, and the trial ended in a hung jury with Theodore completely humiliated.

The Tiltons sent their daughter, Florence, to Europe, and Theodore himself went to Paris and died impoverished; meanwhile, Florence met a wealthy expatriate from Louisiana who was something of a ne’er-do-well, and they had Agnes Pelton in Stuttgart. They moved back to Brooklyn, but Florence’s husband was unhappy and Agnes rarely saw her father—he died when she was 10 from a morphine overdose. The mother became a recluse, still very spiritually inclined, but excommunicated from the church, and it really set the stage for Agnes to turn inward, which she did.

And how did Agnes become interested in art?

She attended the Pratt Institute, studying under Arthur Wesley Dow, the famous art educator who went on to teach Georgia O’Keeffe and many other abstractionists. Dow was one of the people who thought that art should be more an expression of the artist’s experience—it shouldn’t be illustrative.

From there, Pelton studied in Rome for a year, came back, and was part of a group of artists that tended to paint kind of mystical landscapes and figures, the most famous of which is Arthur B. Davies. Pelton’s early works were in that same mode of what was called introspectives, where there were figures communing with the landscape, very dreamy and symbolist.

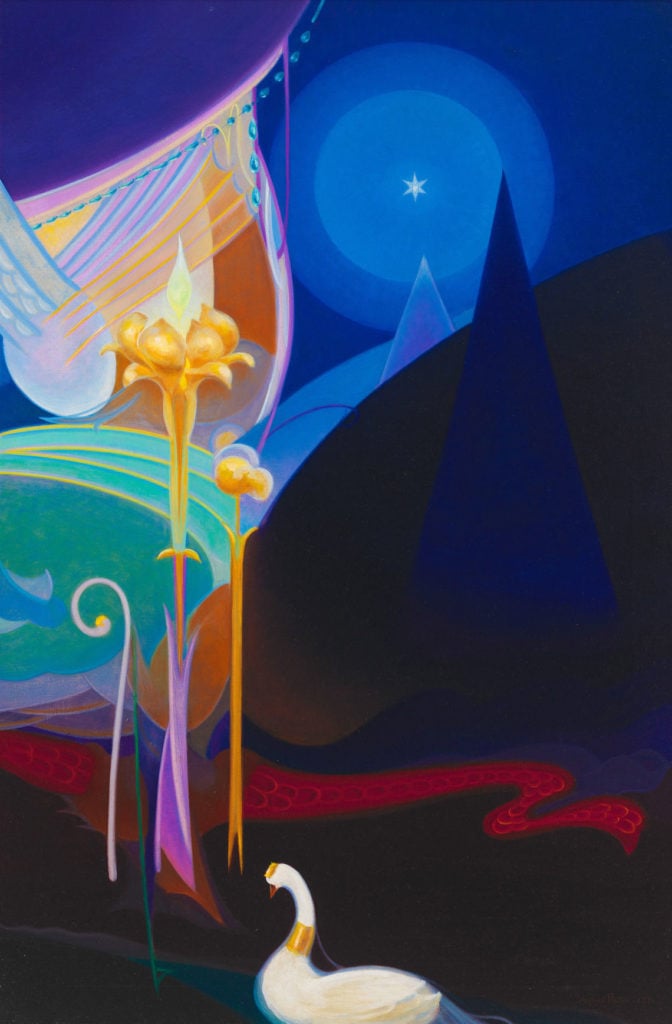

Agnes Pelton, Sea Change (1931). Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Can we talk a little about her psychology? How did this very unusual upbringing and traumatic family history shape the way she was looking at the world and the way that she was presenting herself?

My supposition is that it encouraged her to turn inward. She came from a very spiritual family, so the idea of finding meaning and some sort of spiritual experience was part of her upbringing, but she had to turn to nontraditional ways to find it. For example, she dressed in these very ethereal Greek kind of toga costumes, and began to study occult literature and theosophy.

One thing I’d like to point out is that before she took this mystical turn, she seemed to have the beginnings of a successful art career. One of her paintings was included in the 1913 Armory Show, which is famous because it is where Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase was debuted.

Absolutely, she was in the Armory Show—she was part of a Knoedler Gallery show that helped launch a symbolist group. So she was connected to a group of people who would go on to receive recognition for their work.

Her move in 1922 to Long Island, when she moved into an abandoned windmill, was very radical. After her mother died, who was Pelton’s last connection to the physical world, she wasn’t fully a recluse, but really was isolated there and cut off relations to the art world outside.

Ukrainian theosophist Madame Helena Petrovna Blavatsky. (Photo by Henry Guttmann Collection/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

You mentioned how she fell under the spell, so to speak, of Madame Blavatsky, who was this doyenne of theosophy and a sort of den mother of the occult scene in America. Who else was Pelton interested in?

After Blavatsky’s death, theosophy sort of splintered into several groups, and one of them was a philosophy called Agni Yoga (Agni meaning fire). It was founded by Nicholas Roerich and his wife Helena and was based on the idea of fire being a symbol of life force, something very powerful and deep and a symbol of the spiritual journey to this other harmonious divinity.

I think many people will be familiar with Blavatsky’s worldview, which was really a combination of the world’s religions into one overstory, of a kind of divine path that is followed through many different tellings. But Nicholas Roerich is a much more niche spiritualist, and I understand he had an apocalyptic bent about him. Can you talk about that?

He was kind of a conglomeration of various philosophies and religions and wisdoms, especially Buddhism and Christianity. But he was a very messianic figure. He was a painter himself, he was an explorer, he had a wide range of careers before he created Agni Yoga with his wife, who transcribed the voices she heard, which formed the basis of the practice. He was a very charismatic figure, and one of the paintings Pelton did sort of resembles Nicholas Roerich.

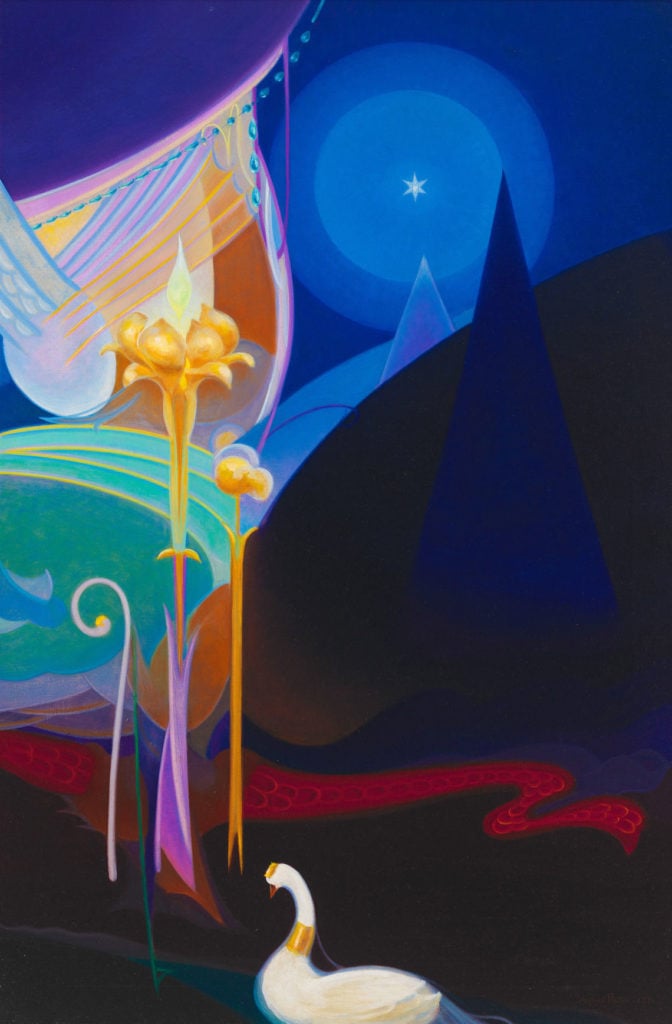

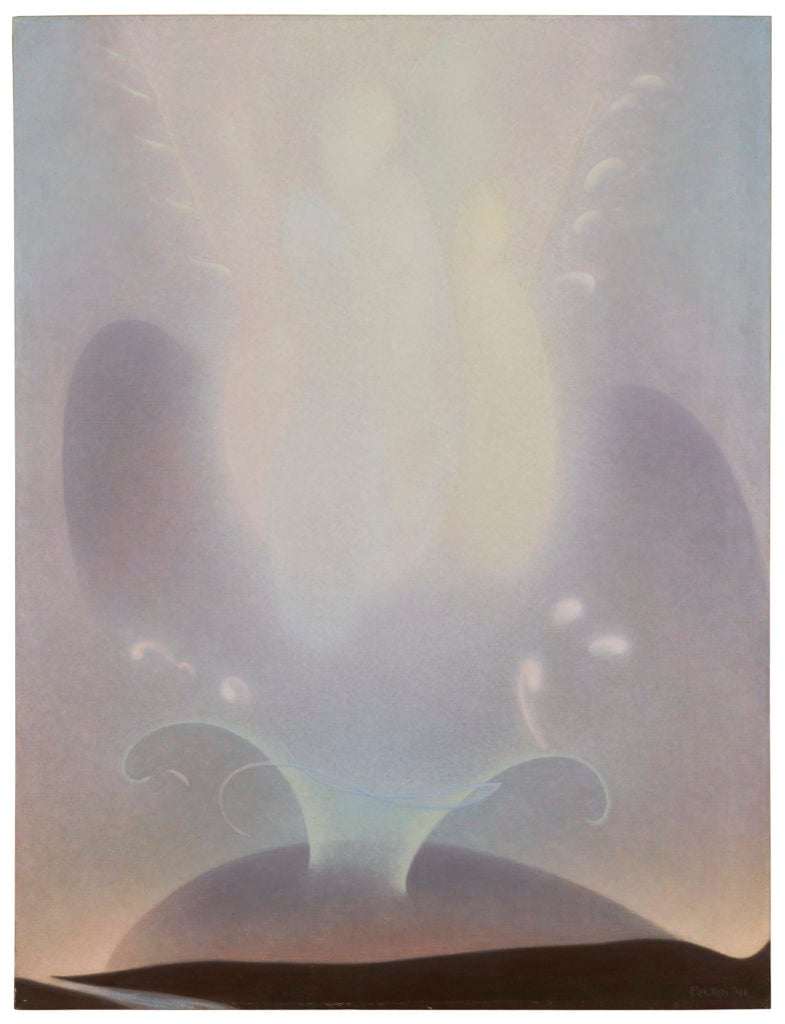

Agnes Pelton, Orbits (1934). Courtesy of the Oakland Museum of California, gift of Concours d’Antiques, the Art Guild of the Oakland Museum of California.

So what impact did all of these different kinds of teachers and mystics have on her art?

Well, it happened in two ways. One, I think it confirmed to her that there was a world that existed beyond the physical, and that the goal of life was to connect with that world.

She also began to incorporate symbols into her work that were part of this whole mystical literature. So stars, for example, were were the symbol of of Venus, the attainment of enlightenment. She would use mountains, which she identified as mountains of aspiration. The work is this very unusual combination of abstract forms and yet recognizable symbols.

She seems to have drawn a little bit from a fellow Blavatsky protégé, Wassily Kandinsky.

She was very influenced by Kandinsky. She read his book concerning the spiritual and art and really adhered to the idea that it is the necessity of artists to present the spiritual, and through form and color, artists can evoke impressions and feelings in viewers.

People often think of Kandinsky as the first abstract painter, but nowadays we know that there is actually an artist who has a better claim to that title, and that’s Hilma af Klint, the mystical Swedish artist who has been very much in the news since she was the subject of a blockbuster show at the Guggenheim.

These two women were virtually unknown in their lifetimes and emerged at the same moment in New York. It’s a wonderful coincidence.

Agnes Pelton, Untitled (1931). Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Did she know Hilma af Klint?

No, she didn’t. I think they both have a similar drive to express a spiritual reality. They both read theosophy and a lot of occult literature. The difference, I think, is that Pelton called her work abstract and it presents itself as abstract, but it does include recognizable images.

So there are images of mountains, many stars. There’s that kind of accessibility that her work has. It engages people with a sense that there’s a meaning that then they want to decipher.

Simultaneous to this mystical content, there’s almost a kind of a Disney-esque friendliness to the composition.

Absolutely. These images of stars and mountains and swans and various recognizable elements create a sense of a magic fantasy. It has a kind of dizzy, light quality that beckons people in.

In 1932, at the age of 50, Pelton moved to a tiny desert town outside of Los Angeles with the incredibly freighted name of Cathedral City. What drew her to that town?

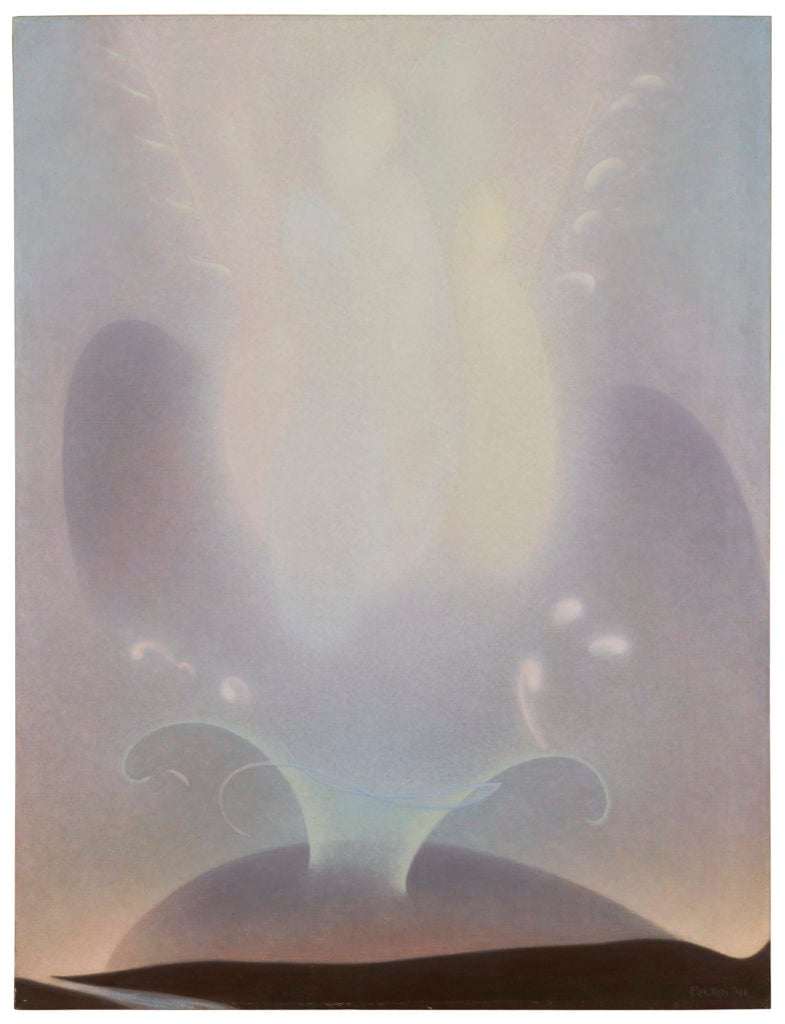

She was first attracted to Southern California because of the spiritual colonies that were there. She’d gone to visit Pasadena in 1928, where there was a group of similarly minded spiritualists. The desert itself was something—I think the emptiness, the sense of expansion, the quality of infinity, the light in the desert. Those are all things that attracted her and became elements in the paintings. The paintings have a kind of soft glow that almost reminds you of what the desert feels like in late evening or early morning.

Agnes Pelton, Ray Serene (1925). Photo by Jairo Ramirez, courtesy of the collection of Lynda and Stewart Resnick.

Pelton once wrote, “I feel somewhat like the keeper of a little lighthouse, the beam of which goes farther than I know, and illumines for others more than I can see.” Can you describe the kind of paintings that she made?

Once she establishes her vocabulary in 1925, she does not stray from it. She didn’t paint for other people. She didn’t paint for the marketplace. In fact, to make money, she painted realistic portraits and desert paintings that she sold to tourists.

The abstract work was the real work, and it was difficult for her to do. She would sometimes only be able to paint one day a week. It wasn’t as if she would go into her studio and think, okay, today I’m going to have an inspiration. She had to wait for those inspirations to come.

Did she ever sell her abstractions?

She sold a few of them, but for the most part, people didn’t understand them. For example, she sold a couple of paintings to a collector who lived near Santa Barbara. The collector gave the paintings to a museum that didn’t want them, so they put them in a garage sale with a price tag of $40. During the course of the day, the price kept going lower and lower. Finally, the paintings were sold for $5.

Wow. Was she able to make ends meet?

She lived very frugally, and then through the sale of these tourist paintings, she was able to make a living. She wasn’t really concerned with fame and fortune in the normal way that artists think of it today—she really did the paintings for herself, to clarify her sense of how to achieve this level of spiritual enlightenment.

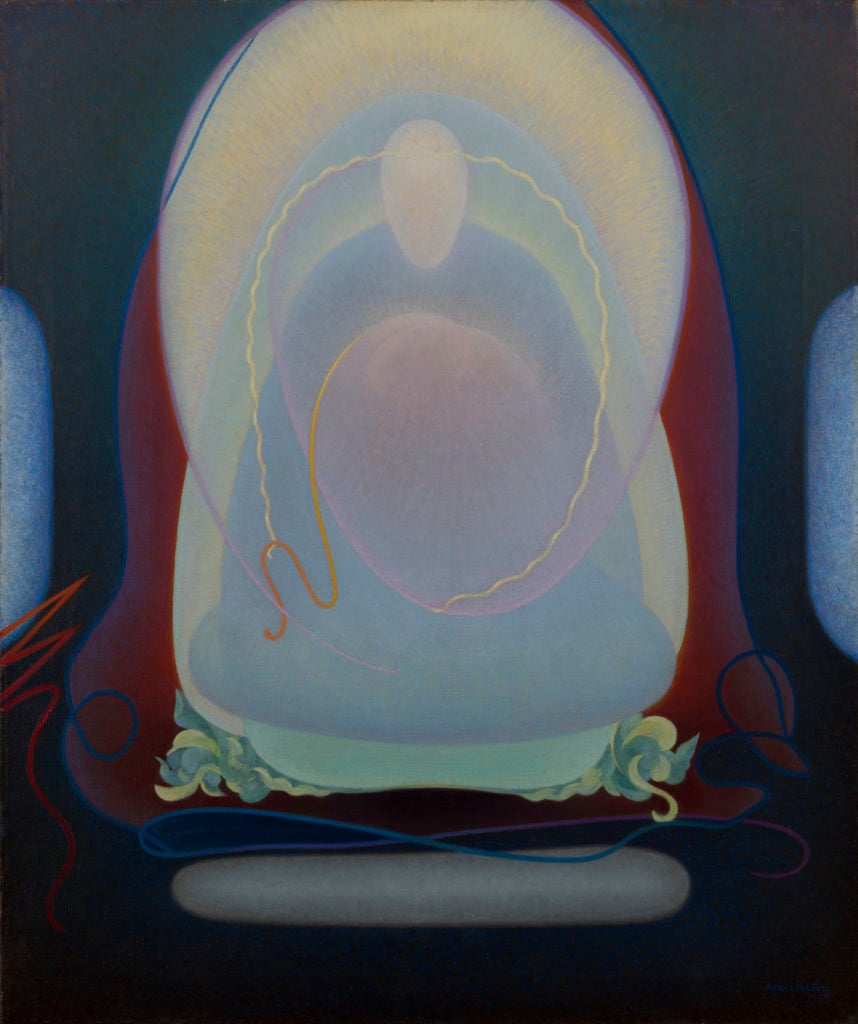

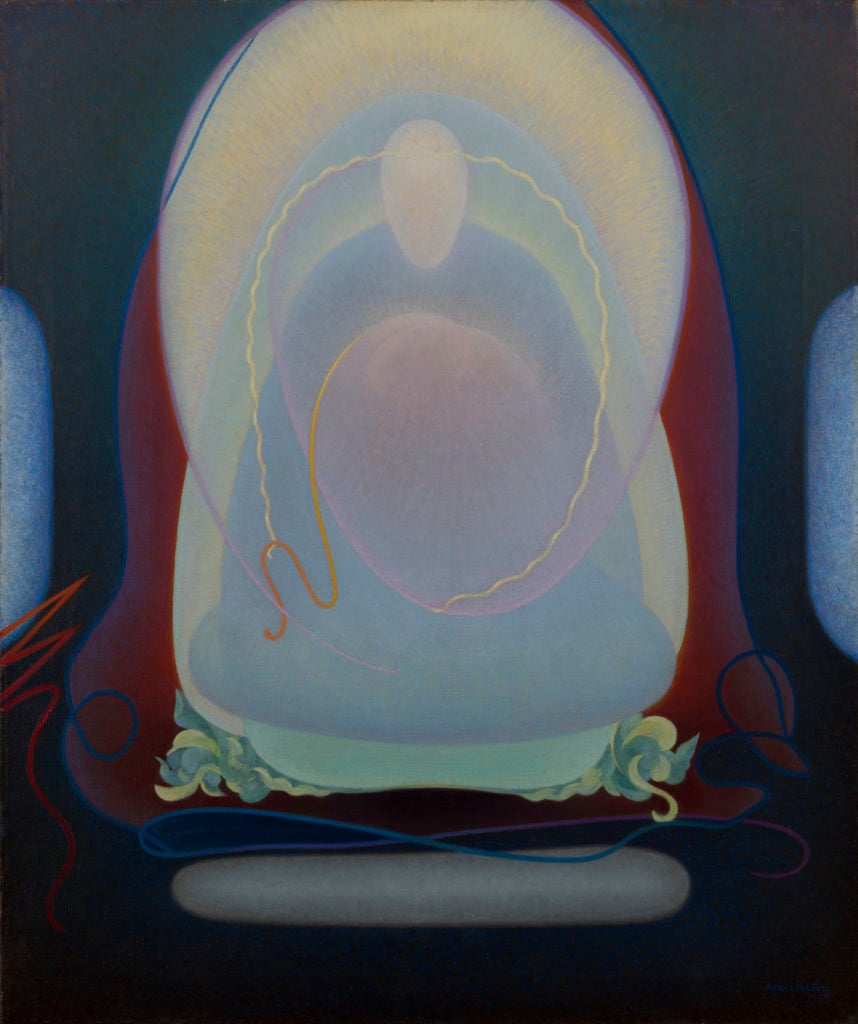

Agnes Pelton, Mother of Silence (1933). Courtesy of a private collection.

One symbol of how personal was to her was that she had one canvas that she called Mother of Silence, which is a Buddha-like figure enrobed in auratic colors, and she considered this to actually be a form of her mother that she could talk to, and turn to for advice in times of distress.

It was either her mother or the sense of the female spirit—she was most attracted to occult literature written by women. Pelton felt that the painting itself had a living presence and she would turn to it and ask its advice about what she should do with her art and with her life. She really felt it was a living icon for her.

Did she ever have any kind of curatorial interest? Was there ever a Barbara Haskell who came along during her lifetime and gave her a spotlight?

No, and that’s why, when she died, the work really went into oblivion. She didn’t have an advocate. It wasn’t until the late 1980s, early 1990s that people began to look at it again.

And that was when her work was included in some important shows?

Yes. There was the landmark show in 1986 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, “The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985,” and then, in 1995, there was a one-person show organized by the Palm Springs Museum, sort of in her neighborhood near Cathedral City.

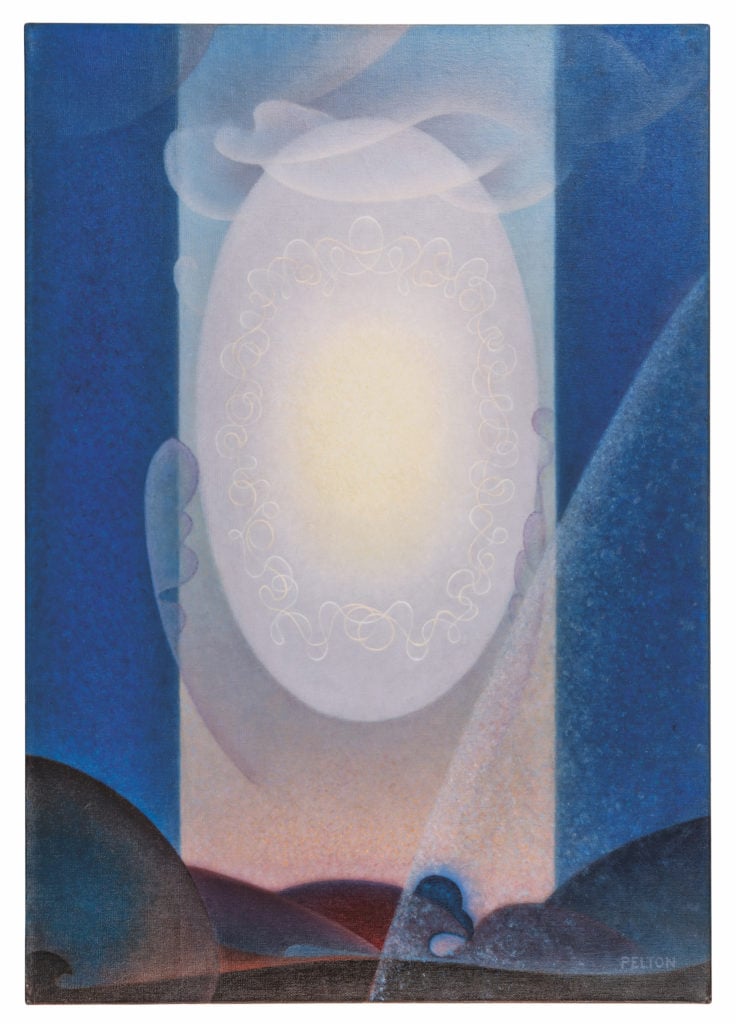

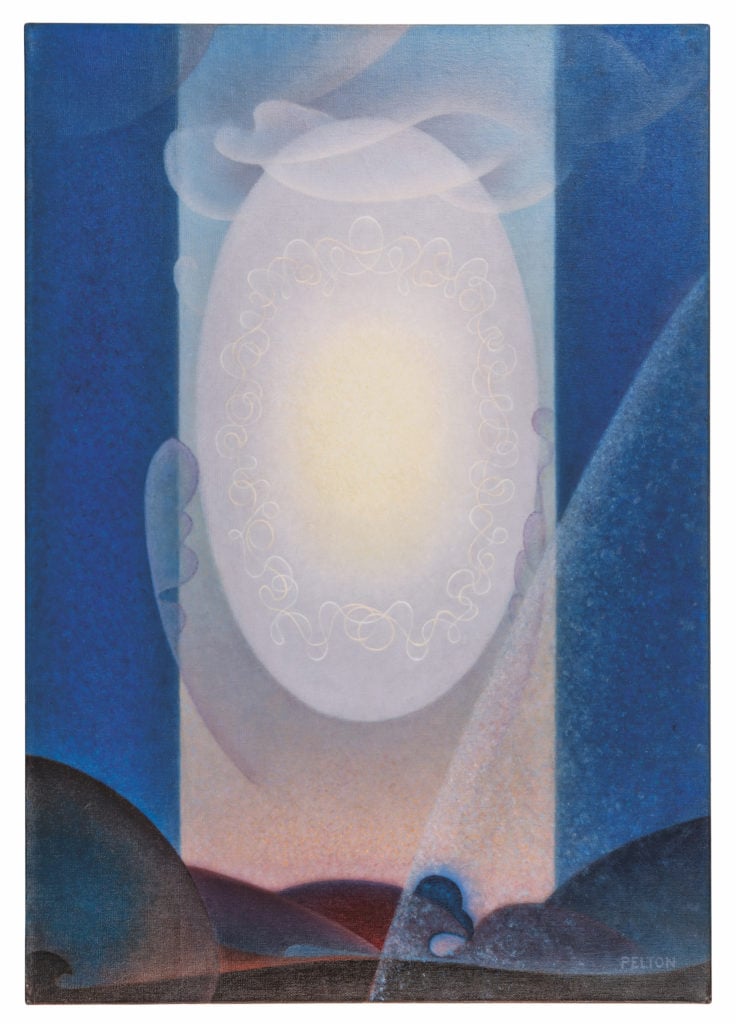

Agnes Pelton, Light Center (1947–48). Photo by Jairo Ramirez, courtesy of the collection of Lynda and Stewart Resnick.

Throughout her career, Pelton would invent new shapes, new compositions, new ways of making her paintings and never repeated herself, with one exception in 1961, the year she died, when she recreated a very specific abstraction she had made over a decade earlier. The painting has sort of a glowing egg shape form suspended in a column of light.

That’s exactly right. Most of her paintings are very different, she never worked in series. Because she brought them out of her own visions, each time it was a different experience with a different set of problems. But it makes sense that she circled back to Light Center, with a glowing orb of light and the circle being a symbol for of infinity, at the end of her life.

So when she died, was she alone?

She never had any heirs or a long-term relationship, but she did have a funeral, and a number of people from the community came. They put one painting up at the funeral, a work called The Blest that her nieces and nephews felt symbolized her entering another level of existence.

Historically, it seems that she may have been a little bit hampered by the fact that she was always compared to Georgia O’Keeffe, who lived in the same remote kind of geography and seems to be tackling similar esoteric, so-called feminine topics. Why do you think that she was the one who really captured the zeitgeist and Pelton lapsed into obscurity?

Georgia O’Keeffe had the great advantage of having an advocate, a very powerful advocate, in [her husband, photographer] Alfred Stieglitz. The other thing about O’Keefe is that the work became realistic at the time she moved out to the desert. She was able to combine realistic, sensuous forms like flowers and mountains with a hard-edge painting technique. The combination of the appealing subject matter and the strong advocate was what made O’Keeffe so popular during her lifetime. Pelton had neither.

Agnes Pelton, The Blest (1941). Photo by Martin Seck, courtesy of the collection of Georgia and Michael de Havenon.

It seems that there is a resurgence of interest in art that tackles subjects that are slightly beyond the rational, and in this time where pretty much every certainty has fallen into question and everything is breaking down, people can’t actually go see your show at the Whitney right now. But is there any lesson that can be found in the story of Agnes Pelton and her art?

In a way, we’re entering a surreal world that none of us has ever experienced. People are more uncertain and more frightened than they’ve ever been before, and, paradoxically, Pelton’s work speaks to us more powerfully now than maybe it did even two weeks ago.

In the late 19th, early 20th century, there was a lot of relocation, urbanization, and industrialization that was changing the way people lived, and there was a lot of uncertainty about what the future would bring. We’re now in a time when that’s even perhaps more true than it was a hundred years ago. But the desire for meaning remains as intense as ever before.