Until recently there was a show at Galerie Lelong in New York called “Gate to the Blue,” and not only was it a tour-de-force introduction to an astonishing artist, it was also the latest chapter in a truly extraordinary love story.

The love story is a very sad one, about an Eritrean-born painter of great talent and deep humanity who died suddenly from a heart attack at the age of 50, and it’s a story that was beautifully told in the Pulitzer Prize-nominated book, The Light of the World, written by his widow, Elizabeth Alexander, who is no slouch herself.

A longtime Yale professor who for the past two years has been the president of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the nation’s largest funder of the arts and humanities, Alexander is arguably the single most eminent figure in American philanthropy today.

So who was Ficre, and what animated his dreamlike paintings? Who is Elizabeth Alexander, and how is she working to change the world? We spoke with the poet, writer, and administrator about that and more.

You can listen to a shortened version of this interview on Artnet News’s Art Angle podcast.

If you can go back to a certain beginning, how did you first meet Ficre?

I met Ficre at what would be the first of many crossroads. I had been living as a poet in Chicago, teaching at the University of Chicago, and I wrote a verse play with a woman, Leah Gardiner, who wanted to develop it as her directing thesis at the Yale School of Drama. So crossroad number one was that I would seek a leave from Chicago and spend a semester in New Haven to be involved with the process, to turn poetry into something for the stage. It meant, in part, turning a very solitary practice into something collaborative, with not only the director, but the actors, set designers, costume designers, and musicians.

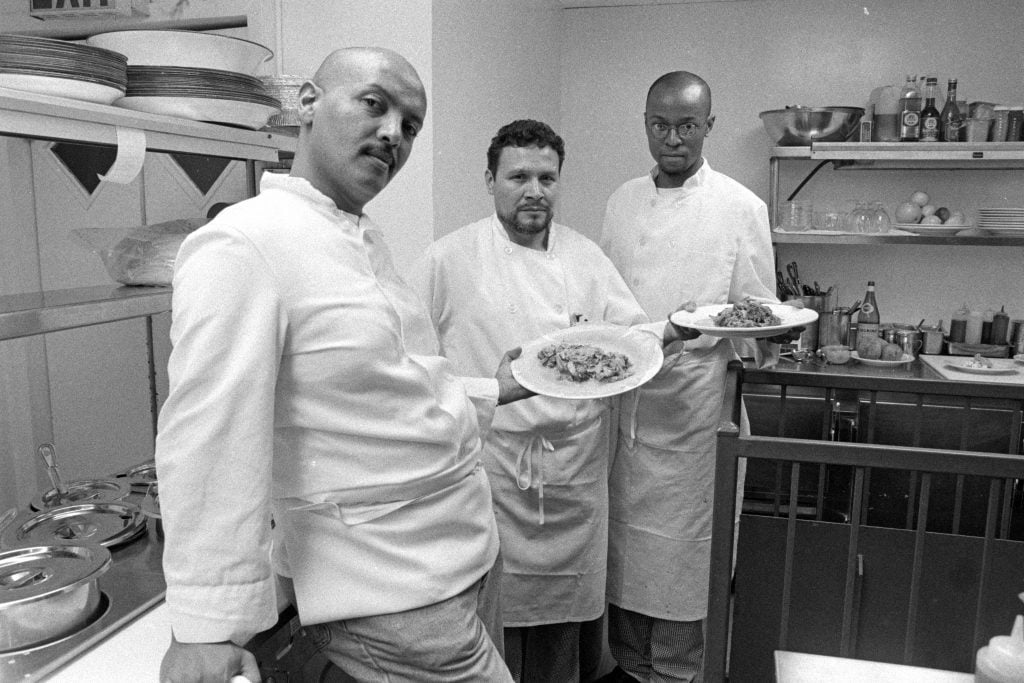

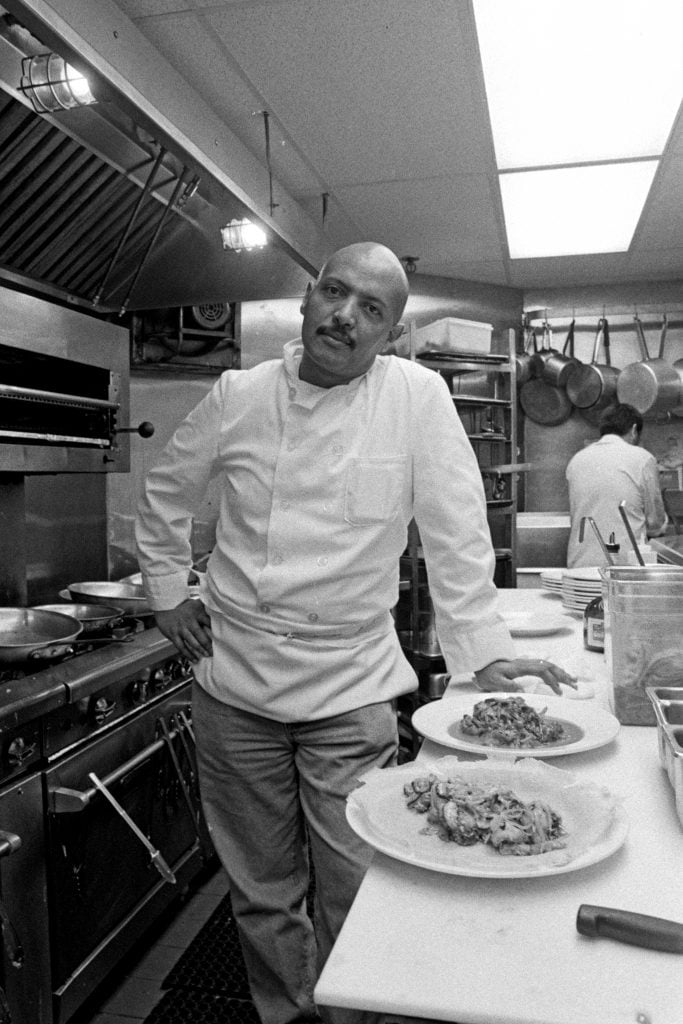

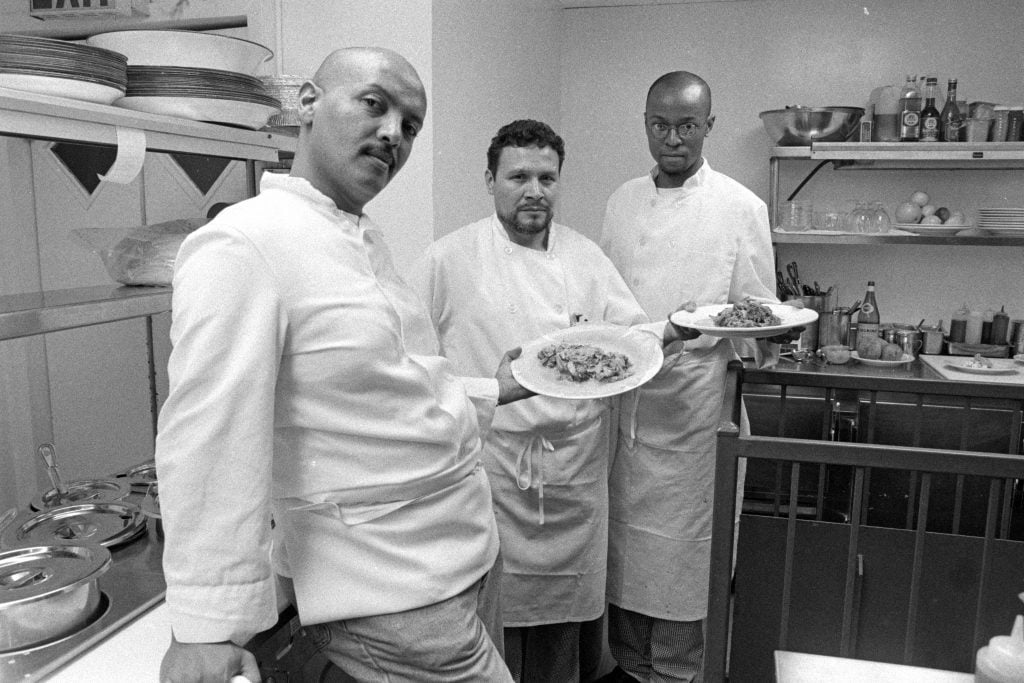

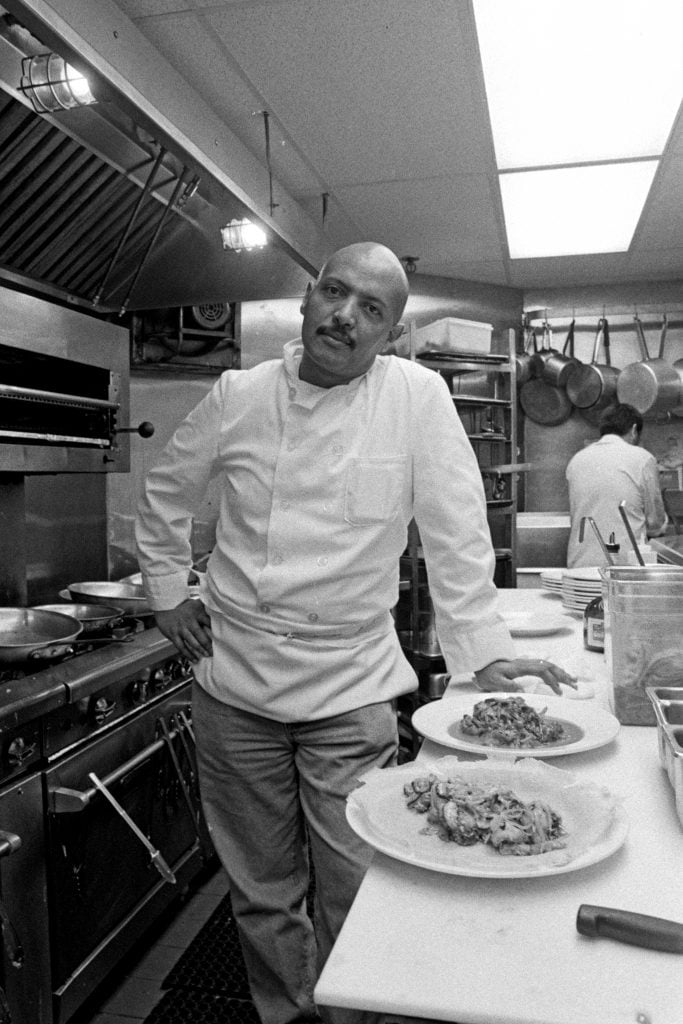

Ficre Ghebreyesus at Caffe Adulis. Photo by Hiroyuki Ito/Getty Images.

So off I went to New Haven and embarked on the very intense and wonderful process of making the play and taught for the semester at Yale. At the time, Ficre and his brothers ran a restaurant in New Haven called Caffe Adulis, and he and his wonderful brothers gave us our opening-night party.

A few weeks later, I was in that cafe again, and I looked up, and here was this person who said to me very quietly, “I saw your play, and I would love to talk about it.” I was meeting a friend, and that friend never appeared. The next time I saw her was at a restaurant in New Haven the night I went into labor with my second child, and I was like, “Oh there you are! A lot’s happened since I didn’t see you a few years ago!”

I was going back to Chicago in a week, but we started talking and didn’t stop. I extended my stay in New Haven for as long as I could. We decided after a week to get married, but told no one because we thought it would seem crazy. We were positively sure that was what we were supposed to do. And that was that. We made our life together, we had our two sons in quick succession, settled in new Haven and into an extraordinary life together.

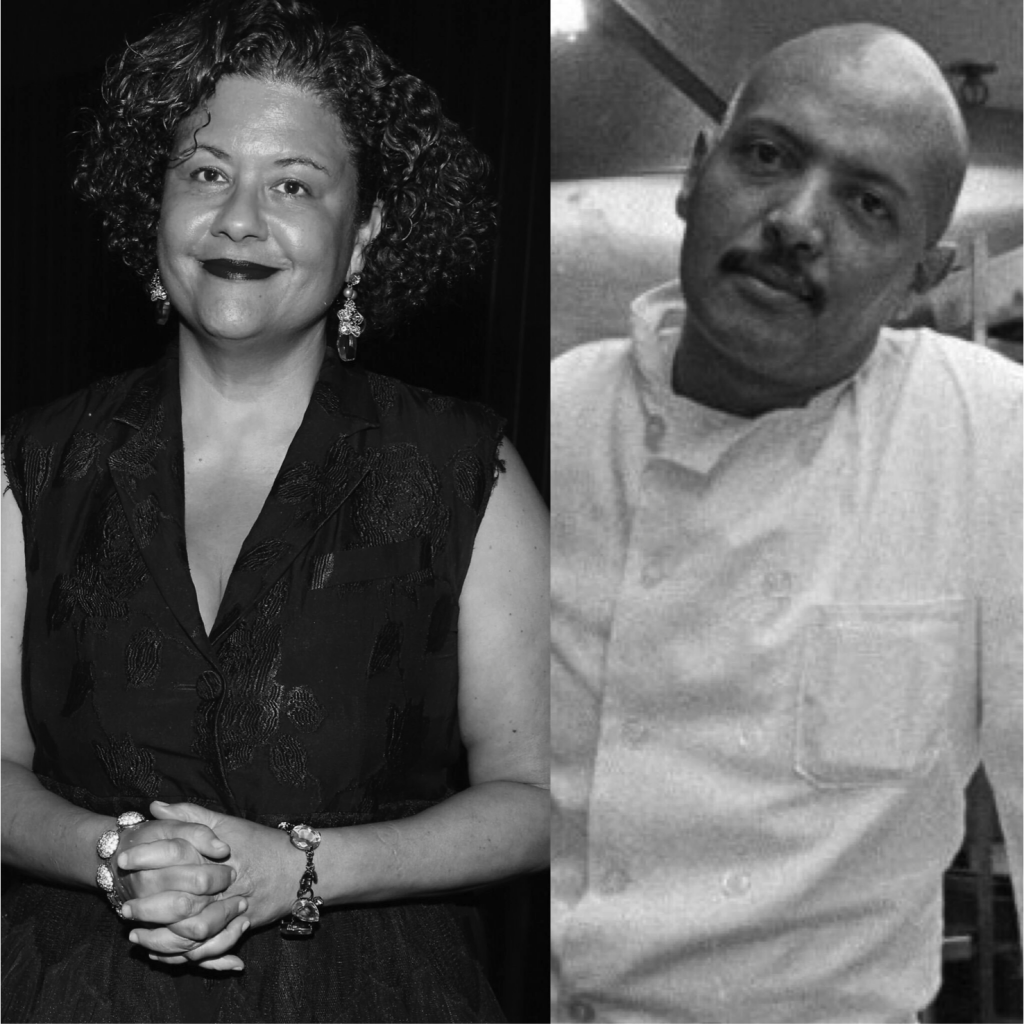

Elizabeth Alexander and Ficre Ghebreyesus. Courtesy of Elizabeth Alexander.

Can you tell us a little bit more about his life before arriving in the United States? What was his upbringing like?

Ficre grew up in Eritrea, in Asmara, the capital city, and the entire span of his time there and after was marked by the decades-long war between Ethiopia and Eritrea, a war of independence. So he came from a place in the midst of a struggle for self-determination and a war in which everyone, including his family, lost someone. The war took a turn when Mengistu Haile Mariam became the dictator of Ethiopia and his regime brought untold suffering of a different order on the lives of not only Eritreans, but also Ethiopians.

He left when he was 16 years old as a refugee for Sudan, on foot. Later he moved to Italy and to Germany, and then, at the age of 19, to the United States. He eventually, after a stop in California, landed in New Haven, where he would spend the rest and the longest stretch of his life.

Ficre Ghebreyesus at Caffe Adulis on April 19, 2000. Photo by Hiroyuki Ito/Getty Images.

Ficre also spent some years in New York, always working, usually in multiple restaurant jobs, doing student activist organizing work, and always living a life of curiosity and creativity. So when he was in New York, he marveled at the museums, especially at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he would go and disappear all day.

He found time to study painting at the Art Students League, and also got a chance to work in the great Bob Blackburn’s printmaking workshop. He was and remained a young man of tremendous energy, tremendous purpose, and someone who always felt fortunate to have the opportunities he did.

He was always hungry for books, for music, for ideas, art, and righteous politics, too. He was a citizen of his place, but also of the world. He was a really smart political theorist in the way that he understood political movements in history. And I would often marvel at how someone who had experienced that kind of death and fear and suffering was also a person of extraordinary joy who lived life very fully.

What was his art practice like at that point? Was he very invested in his painting?

I would say he probably was doing more drawing and printmaking than he was painting. When he did move into painting, the early work was always set in Eritrea. A lot of it recalled scenes of war, as did some of his photography; a lot of it was very literally a dark palette. I found it so interesting that there are always figures in his work, but they are abstracted. There are landscapes in it, but they’re abstracted. So there’s always an aspect of his work that is tethered to the real, but a kind of driving sense of shape and color and a dreamy kind of mood.

His palette changed a lot later on, but I would say that that space between abstraction and figure and landscape was always where he was playing.

Caffe Adulis. Courtesy of Flickr.

So he and his brothers owned the very popular New Haven restaurant Caffe Adulis, which you once described as serving Eritrean fantasia foods, which I think would make anyone hungry. How did he progress from being a restauranteur to becoming a full-time painter?

He really saw his creativity along a continuum. But once we were together, the restaurant was very well established and we had these kids back to back, just a year apart, so his previous life of cheffing and closing the kitchen at midnight and painting until dawn was just not tenable. When our kids were very small, I said, “You know, if painting is really the thing you’re going to try to do, let’s do it.” He applied to Yale’s art school and got in, and then he was able to become executive chef—where you leave the cooking every night to all the chefs you’ve trained—and devoted himself to making paintings.

One of the most fascinating points that seemed to come up in the book is whether or not he should sell and show his art.

Yes, that was a recurrent point of disagreement between us. I have my own artistic practice, so I do understand that you’ve got to get it right. But when people saw his work, it was so powerful, and I felt it should live in the world.

He was eerily clear that what he needed to be doing was making, not peddling. The thought of self-promotion was anathema to him, and so the business of putting his work out in the world just felt constitutionally not what he was supposed to be doing.

Ficre Ghebreyesus, The Sardine Fisherman’s Funeral, (2002). Courtesy of the Estate of Ficre Ghebreyesus and Galerie LeLong & Co.

He refused people who would even beg to buy his work. Did it seem like there was something he was waiting for?

I can only look at it now in retrospect, and given that he passed so unexpectedly with no warning whatsoever, and that he left behind a body of work that is so extensive and so complete… I don’t know that he had premonitions of his passing, but I do know that he was positively clear about what he should be spending his time doing, and that was making art, being a good human being, and caring for his family.

You described how his early art had a very dark palette, and it seemed to tell of his early story. And then as time went on, his palette warmed up and it became very joyous, with these incredible works it seems like you could almost step into. How would you say his work evolved, and what drove that evolution?

A story that I tell in the book that feels like such a Ficre story is that, the last home we lived in had a very big yard. He was quite a gardener, and grew vegetables, trees, flowers, all sorts of things. And when we were thinking about moving into that house, he said, “Baby, this is Africa. This is our compound. This is how I feel here.” And so I think that he landed safely.

This was someone who grew up in a magic compound, but had soldiers break into his home. So that landing and that safety was, if you will, a place of infinite color.

I don’t think his later work is just joyful though. Even where there is that explosion of color, you can see spaces where other darknesses are remembered or are a part of that landscape. What opens up is not just joyful color, but rather incredibly complex color. The power of color itself. Landing meant that in his imagination, he was free to do anything he wanted.

President Barack Obama greets American poet Elizabeth Alexander at the White House. Photo by Mark Wilson/Getty Images.

In 2009, you wrote and recited a poem called “Praise Song for the Day” for President Barack Obama’s historic first inauguration. It includes the line: “say it plain, that many have died for this day.” You’re talking, of course, about the inexpressibly tragic history of the Black experience in America that led to Barack Obama’s presidency. How did Ficre, as an African by birth, talk about this moment and experience this moment?

In the African American experience, there are people who have sacrificed and died so that all Americans might have certain privileges. I don’t see it as fundamentally tragic, I see it as an experience characterized by an enduring freedom struggle. But I also think that African American culture has ironically defined for all of us what it is to be human, because if you think about the incredible cultural production of people who were defined as three-fifths human beings, brought here and lived here for so long as property, but have nonetheless created a world culture at its best.

It has been influential all over the world. That’s extraordinary. For Ficre, he was always a Black man of the world, as someone from Asmara, who was Eritrean and East African, he became an African American. I’m not referring to citizenship status per se, but rather, he lived as a Black man in New Haven, Connecticut, for the majority of his life and he was part of a very diverse community.

Ficre died in April 2012 of a sudden heart attack while he was jogging on his treadmill. You write about that heart-wrenchingly viscerally in your book, and you impart his tragedy in a way that few people who read it will ever forget. How did his death change the course of your life?

Once a mother always a mother. Once my children were born, that was clearly my primary responsibility. When their father died, even to say the word responsibility took on a whole different depth and meaning instantaneously. In addition to just caring for them and literally feeding them, our lives didn’t end. It was tragic that we lost Ficre, but he had lived so many lives and survived so many things.

That was another crossroads, and we had to keep walking. A year after Ficre died, I moved us to New York City, which was very hard. Of course, they didn’t want to leave the life they had. But I knew it was something that we needed to do, not to reinvent ourselves from scratch, but to show that we could be open to life changing.

Elizabeth Alexander, president of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, is awarded the W.E.B Du Bois Medal during a Ceremony at Harvard’s Sanders Theater. Photo by Jessica Rinaldi/The Boston Globe via Getty Images.

When you moved to New York, life changed for you in a very marked way. You took up a professorship at Columbia University, and then in 2016, Darren Walker, the president of the Ford Foundation, came to you with the opportunity to dramatically transform your career. How did you come to be the director of creativity and free expression at the $13.7 billion philanthropic powerhouse that is the Ford Foundation?

I should say that the big thing that happened before that was that I wrote a memoir, and I mention that because I would not have imagined I would have shared my life in that way. But to have leaned into writing that book and then finding that it was meaningful to a lot of people—that felt braver and harder than actually going to work at the Ford Foundation.

Darren Walker, he saw in me someone who was chairing an interdisciplinary department, who was building community, who was working in the arts community, who understood something about institutions and how to maximize them and move them as best I could from where I sat in a positive and social-justice direction. He saw all those things in my work, and I thought that I just had to take this opportunity. And it turned out I was good at it! And it turned out that there was so much growing that I was able to do outside of a university context if given the opportunity.

Director of Brooklyn Museum Anne Pasternak, Marilyn Minter, Madonna and Elizabeth Alexander. Photo by Kevin Mazur/Getty Images for Brooklyn Museum.

In 2017, you worked with the art collector Agnes Gund to design the Art for Justice Fund, a $100 million charity. The fund was dedicated to reducing mass incarceration and pushing through prison reform, long before the conversation went mainstream. Why did you choose to focus such philanthropic heft on prisons?

I think what was so powerful for me, first of all, was to see somebody put money to use [in this way]. What can that do in the world? What does it mean for someone of tremendous wealth to say, “I don’t need everything. I want this wealth to improve our society, and I want to learn deeply while I do this work”?

Even in what we call big philanthropy—Ford and Mellon are both tremendously endowed places—one thing you learn very quickly is that there’s never enough money for all of the institutions. So when you think about putting resources to work that are private and otherwise not going to the kinds of society-building efforts that we work on in philanthropy, the opportunity was just a pretty amazing one, and an important model for what philanthropy needs in order to be really effective.

Part of the co-design was thinking about funding in a way that would help people to create empathy and feeling what it means to step into the life of someone else. This just comes back to who I am and what I have been stirred by my whole life—not just the visual arts, but art in general. What else can make you feel cry, laugh, act? Art can do that.

So how did you come to transition from the Ford Foundation after this huge achievement to taking over this multibillion-dollar foundation, the Mellon Foundation?

I thought I was going to go back to teaching the further I got into the process of applying. And yet, as I talked with people on the board, I said, “If you want me to do this, we really need to sharpen the lens so that all of our work passes through a social-justice lens, to address how are we thinking about contributing to a more fair and just society.”

I really did love working at Ford, and the only piece that wasn’t there was my lifetime commitment to higher education. And here was Mellon, which had an arts, culture, humanity, and dedicated higher ed arm. I’ve been in that world my whole adult life, so it seemed that again, I was at a crossroads. It seemed that I really was supposed to be doing this, that this was the institution where I really could contribute something and also learn and grow and have responsibility for leading a community, as well as putting forward ideas into the world with our grant-making.

Both Ficre and I wanted our kids to be safe and comfortable, but we also knew early on in our relationship that we wanted them to have resilience. I want them to know they can reinvent themselves. I want them to be survivors, and so that’s what I’ve tried to model as well.

Ficre Ghebreyesus, Red Hats and Balloons (ca. 2002–07). Courtesy of the Estate of Ficre Ghebreyesus and Galerie LeLong & Co.

Speaking of reinvention, since you arrived at the Mellon Foundation, you’ve made some staggeringly impactful moves. You pledged to give $500 million in aid to arts and humanities organizations, including a $10 million fund that gives out $5,000 individual grants to artists. In June, you announced a reorientation of the foundation towards social justice, coming in the middle of a very chaotic and uncanny year. What is the role that art plays in social justice?

I believe that the principle of philanthropy is super simple. Whatever resources you have access to, I was taught to share those resources and maximize them. And in recognition that there is so much inequality of resources, to have a critical approach to what it means to distribute those resources. I’ve always thought about coming from an African American studies perspective. We know that some stories aren’t told, some stories are mis-told, and some lives are marginalized.

In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, I think many more people are seeing and understanding the disproportionate suffering of Black and brown people and the way that certain people in certain jobs are put into harm’s way while others are allowed to stay safe.

As someone who also funds the arts, I’ve always been attuned to what less resourced institutions are doing, and knowing that artists themselves are suffering huge unemployment. I just kept thinking, how can we help?

Of course, this crisis was quickly followed by the explosion of police violence that lead to the murder of George Floyd, of Breonna Taylor, and the vigilante, civilian racist violence when Ahmaud Arbery was murdered. This is not a new story, but wow, we are living in a surreal time. I feel dependent on the artists, writers, and scholars to help us understand what we have been going through, what we have been living through. We won’t understand it. And I don’t mean in a very literal way, but I think that it’s the arts that have the capacity sometimes completely abstractly to capture humanity, to capture the soul.

Installation view, “Ficre Ghebreyesus: Gate to the Blue.” Courtesy of Galerie LeLong & Co.

To return to Ficre, it’s amazing that in this chaotic year, he’s receiving his first major show at Galerie Lelong. How do you see the show at this particular moment in time?

Isn’t it extraordinary that it’s happening now? When he died eight years ago, he left behind 1,000 paintings, countless photographs and works on paper, truly a body of extraordinary work. And that work would ultimately need art professionals to shepherd it, to care for it, to make sure it’s safe, to love it, to speak for it, to know it, to believe in it, and to help bring it to the world.

It’s been amazing working with Galerie Lelong because they bring reputation, expertise, and knowledge. But it’s also allowed a profound exhalation for me to know I got it in the hands of people who will take care of it as professionals.

Although we would have loved to have a big opening night party and dinner in Ficre’s memory, it was miraculous to have an opening over Zoom, which meant that this human of the globe could be celebrated by all the people of the world he touched.

How do you think he would feel about this moment, having kept his work private and in incubation?

I know that he would be tremendously proud of my vigilance. I think he would be tremendously proud of his sons, to see people being so moved by his work, and it’s rare for a person from his generation of Eritreans to make their way as an artist. So I know he would be very proud about that. We were very intertwined in our work and I don’t think he was just holding out because he was shy. I think he really was trying to get somewhere. And I think that had he lived, he would have gotten to the place where he felt like, “Okay, it’s time to share.”