The Big Interview

The Story of artnet: How Founder Hans Neuendorf Rose From the Rubble of World War II Germany to Transform the Art Market

In the first part of a series marking artnet's 30th anniversary, Neuendorf opens up about his early life.

In the first part of a series marking artnet's 30th anniversary, Neuendorf opens up about his early life.

Andrew Goldstein

It’s impossible to talk about the evolution of the art business into a global industry over the past three decades without understanding the role played by artnet. Founded in 1989 as a database of art prices—a groundbreaking innovation in a marketplace long defined by obscurantism and information asymmetry—artnet was the first art business to go online; its news platform, artnet Magazine, became the second-ever online publication (after Salon); its gallery network served as many galleries’ first online presence; and its auction platform led the way for legacy auction houses to enter the digital era. With its emphasis on transparency and efficiency, artnet did much to create the conditions for the headlong modernization of the art market. And it never would have happened if not for the stubborn, quixotic, and deeply idealistic vision of artnet’s founder Hans Neuendorf.

Now 82, Neuendorf led an outsize life in the art world even before artnet. Coming of age in Hamburg amid the wreckage of World War II and entering the art business while still in his teens, he organized the first Pop art show in Germany, championed important artists (like Georg Baselitz) in the face of widespread skepticism, single-handedly brought Sotheby’s to Frankfurt, and created a highly successful art fund. In starting artnet, Neuendorf overcame an unceasing parade of crises and challenges, keeping the company going by selling artworks to fund operations and maintaining a conviction—he might call it naiveté—that success was always right around the corner.

To mark the 30th anniversary of artnet, and to better grasp the historical context that gave rise to it, artnet News editor-in-chief Andrew Goldstein sat down with Neuendorf in his corner office atop the Woolworth Building to talk about his life’s work. The following interview is the first installment of a multipart series reflecting the sprawling four-hour conversation.

You were born in Hamburg in 1937, at a time when the German war machine was cranking up and the clouds of World War II were gathering.

Yes, it was before the early days of World War II, and I saw a good deal of it. I saw the broken army walking home from Russia for days and days in rows of four—the crippled, badly clad, and sick army was coming home. Those were young men, and they camped out in the woods near our home underneath the tall beach trees. The soldiers hadn’t received any information about where to go or what to do, nor did they have any money or transportation, so what they did is they carved little things out of wood they found there, like nice, complicated walking sticks. As a boy, I would trade with the soldiers—it was my first attempt at buying and selling something.

They wanted cigarettes, and there was an American army camp not very far away where the soldiers received so many cigarettes that they threw them away half-smoked. As boys, we would go there and pick them up and put them in a little containers, and I would bring them into the woods to trade with the German soldiers for a walking stick or something else, like a warm pair of boots that they were still carrying around. I would then go to the farmer and trade these things for a little pig or some other food. That’s how we survived.

German refugees after the end of World War II in Europe pass through Hamburg during a snowstorm, dragging carts piled high with their belongings. Photo by Keystone/Getty Images.

How old were you at this point?

Well, that must’ve been in 1946. So I was eight.

What were your parents doing at that time?

My father had been in the war. He was in Greece as a service soldier, and when he returned he had to walk home at night, because he had to go through territory in Serbia where there were guerrilla fighters in the bushes who were not in a very good mood about Germans, and were hunting them down. There were 20 when they left Greece, and three arrived home alive.

I imagine the Germans had shed their uniforms and were traveling incognito?

Oh, no. They had nothing else to wear. That’s why they walked at night. They also didn’t have anything to eat, of course, and were surrounded by enemies. That’s what my father told me.

What about your mother? What did she do during the war?

Well, she had three boys—I was the oldest one—and we had been evacuated from Hamburg when it came under heavy bombing from the British Air Force. The British were humane in the sense that they proceeded systematically—they’d bomb one street one night and then the other side of the street the next night, and so we figured out when we had to leave. We lived in an apartment, and I remember we had to evacuate at night in our nightgowns. We got onto a horse-drawn flatbed that took us to the station, where we caught a train out into the country. The government provided a little house for families with children, and we were privileged because my mother had three boys, and boys were what Hitler wanted. That was ‘43, and I was five or six.

A man traverses Hamburg in the wake of World War II. Photo by dpa/picture alliance via Getty Images.

How did your parents get reunited?

Well, we were staying in this little hut, and I don’t remember how long we were there but it was until at least a year after the war ended. One day my mother sent me into town to fetch some bread—at that time the way they did bread was to mix sawdust into the dough—and when I was going there to get that a soldier passed me in the road, and that was my father.

Incredible.

I didn’t recognize him—I hadn’t seen him in three years, and I had been a small child—and he called after me because he wasn’t sure. He said, “Hans.”

Were the roads filled with returning soldiers?

The whole country was completely in pieces when my father came back. Many, many fathers didn’t come back. They were fleeing East Germany, they were fleeing from the Russian army, because the Russian army had a very bad reputation, with the killing and everything else that was going on. But we were friends with some of them. There was a prisoner-of-war camp near where we were, and they were Russians mostly—very sweet boys, 18, 19 years old. Farm boys, even. They taught us how to catch fish without a hook: you go very slowly, and then you have to grab it. They worked for us, chopping wood for the stove and digging the garden, because we had no vegetables—we had to grow it all ourselves. I had a little patch. I was growing tobacco, because I thought that was a good business.

You were obviously an entrepreneur from a young age.

Yes. That’s why I began to trade with the farmers, because the farmers had food and we didn’t have any food. Sometimes, though, once the farmers had harvested the potatoes they would also invite townsfolk like us onto the field so we could grab whatever was left over. So, these were potatoes that had been cut through the middle and things like that, and we boys would bring these home so we would have some food. And so we thought, “Oh, it’s good to do that, but a great idea would be to get the whole potatoes from the fields that they haven’t harvested yet.”

Good thinking.

So we went at night, my brother and I, and there was a deep ditch around the field. They dug that on purpose, because if you fell into the ditch you couldn’t get out. It was slippery and hard to climb the walls. But we got onto the other side and dug up some potatoes and put them in a bag. All of a sudden, the place was ablaze with light, and they were shooting at us. They didn’t know we were kids. Bang bang. They had to protect the potatoes. Obviously, other people had tried to steal them. Anyways, there was no order then, so that’s what we did.

Eventually you left the countryside. Where did life go from there?

We came back to Hamburg, and I went to school and started studying.

Office buildings in Hamburg that were rebuilt after destruction in World War II, at the City Hall Market Square in 1955. Photo by Three Lions/Getty Images.

What did your parents do?

Well, my father’s business was ruined. My father was adopted and he married my mother against the will of his adoptive father, and that guy just disinherited him, even though my father had built their business up. They had an importer of exotic tropical woods. And so he lost all of that, and that meant he had to go and become a traveling salesman, selling all kinds of things. Unsuccessfully, I would say.

What about your mother?

My mother also started to work. She worked for a movie company that did a weekly newsreels. That was before television of course, so you had to go to the cinema to watch the news. It had mostly been used by Goebbels as propaganda for the war, and then afterwards they had news from all over the world in bits and pieces where you could actually see some things that you had never seen before or heard about, because there wasn’t really a press yet and all that. She was working at the archives, and she had something that they all liked very much—she had an unusually good memory. Because they had thousands of cans of film and would say, “Where was the reel where this or that happened?” and she always knew where it was. So that’s how she made some money.

How did you start to become interested in art?

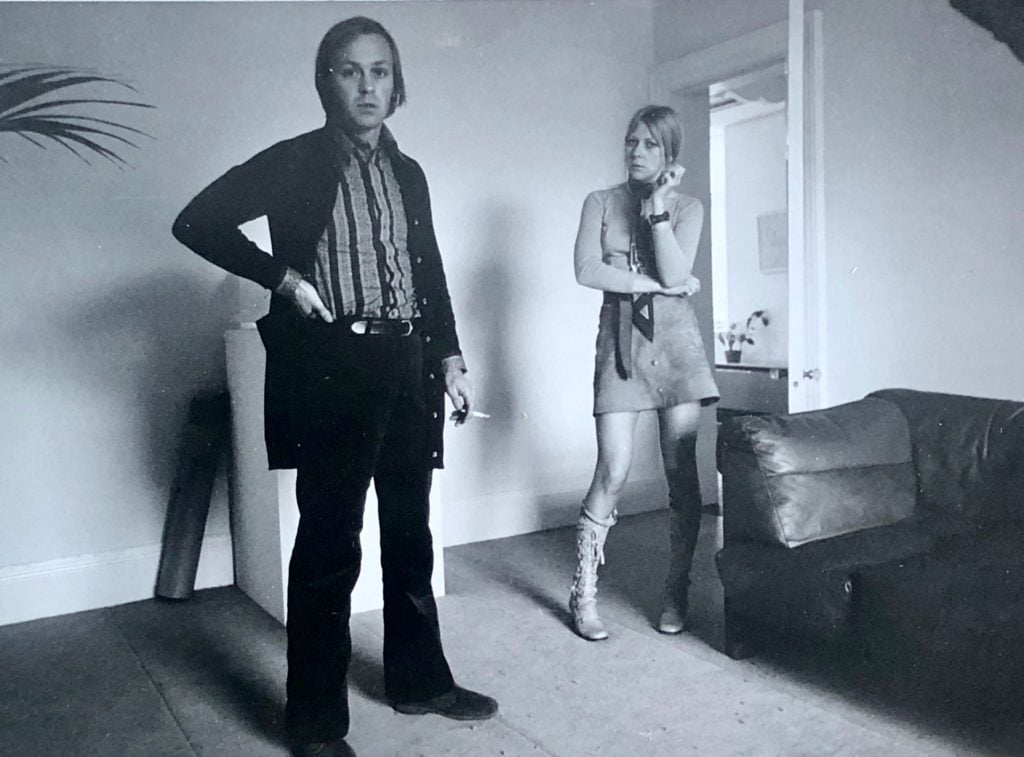

When I was 10, I switched to another school in a different area, and I had to take the train. And at the train station was a bookstore, so when I was waiting for the train I would look at the books. They were tiny little books—the size of a matchbox—and they had colorful reproductions of artworks on the cover, which was something I had never seen before. These were abstract German artist of the time, like Troekes and Cavael, people you had never heard of. But I thought it was fascinating. I couldn’t have imagined buying them, but what I ultimately got for Christmas was Knaur’s Lexicon of Modern Art, and it had biographies of all the big artists like Chagall, Matisse, Picasso—all of these people. That’s what really got me interested. I read that back and forth until I knew it by heart, practically.

Knaur’s Lexicon of Modern Art. Image courtesy of Amazon.

Did you go to museums as well?

I went to the museums, but I had a school pal whose father was an architect, and I used to go over to his house a lot. The father had a collection of big paintings by Kokoschka, Munk, Kirchner, Heckel, and all of those. He had kept them through the war, and I looked at them and I asked him straight out, “How did you do this? This must have been very expensive.” And he said to me, “You must buy them when nobody wants them yet.” So that was my ticket.

When did you begin to think about buying your own works of art?

My father had a friend, he was a Russian cellist. And my father lent him some money, and before he went away the guy left him a big trunk of things that he couldn’t take with him as security. And he never turned up again. We didn’t know if he was alive or dead. Years afterward, you know what? I found the trunk in the basement. I opened it up, and I looked around, and there I found a [Lyonel] Feininger. It was small work, made out to the neighbor’s children I lived next door to. He made a lot of work for children, including little model trains he made from wood that he carved and painted. Anyway, I found this watercolor. And I knew what it was, because I had read about all the artists.

What did you do?

I said to my father, “Can I try to sell this?” “By all means,” he said, “go ahead.” So I took it around, and there were only two galleries in Hamburg at the time—well, one was not really a gallery, it was an art dealer who lived in a very nice villa. He must have been quite wealthy. So I showed it to him, and he offered me 3,000 marks, which was a huge fortune. I asked my father, and he, “Yeah, go ahead.” The dealer gave me cash, and that’s how I started.

An early cubist painting by Lyonel Feininger from 1912. Photo: artnet.

How old were you at the time?

I was 18 or so.

That’s pretty precocious.

Well, I was interested in it, and it turns out it was worth money. Anyway, I gave my father the money, and he lent me 300 of the 3,000 marks, because I had this idea I wanted to go to Paris hitchhiking. So I hitchhiked to Paris and I bought some prints by Matisse, and Picasso, and things like that. Not expensive at the time.

Which gallery did you buy them from?

Well, among others, Heinz Berggruen. He had a little gallery on Rue de l’Université. Since then I’ve seen him many times.

Did they think anything was odd about such a young art collector coming in their gallery?

No, at least they didn’t say so to me. And I paid him cash for some prints. He, very ungenerously, gave me a 15 percent discount, even though he could have given me 30, because he had published the prints himself, you know. Anyway, I took them home and sold them to my dentist.

Really?

Yes, and fathers of friends and people like that. This was a time in the ‘50s in Germany when some money was first being made—mostly by dentists, doctors, lawyers, and people like that. And they had the education and the desire for some art, which had been forbidden in Germany for a long time. So, I did quite well. The price difference, on retail, between Germany and Paris was like 50 percent. So what I was buying for 100 marks I could sell easily for 200 marks, and I was still below market. So that was how I financed my studies.

I studied in Munich, mostly, and then I would go to Paris hitchhiking. There were no autobahns or thruways of any kind. Sometimes it took me three days in the winter, when it was really cold. I had to stand on the street, hitchhike, go to Paris, and then back. In some sense, that’s how I lived.

What did you study when you were going to school?

At the university, I studied philosophy and art history and psychology.

Did you think of art as a career path?

I wasn’t thinking of a career, I was just following my instinct of what I liked. We didn’t think the way we do now—you didn’t do something for money. That was far-fetched. What you did was you followed your instinct, what you liked, and somehow maybe something was going to come of it. Of course, I financed my study with art, so I was quite aware that you could make money with it.

So, in the beginning, you spent 300 marks on art in Paris. How much did you make off of that?

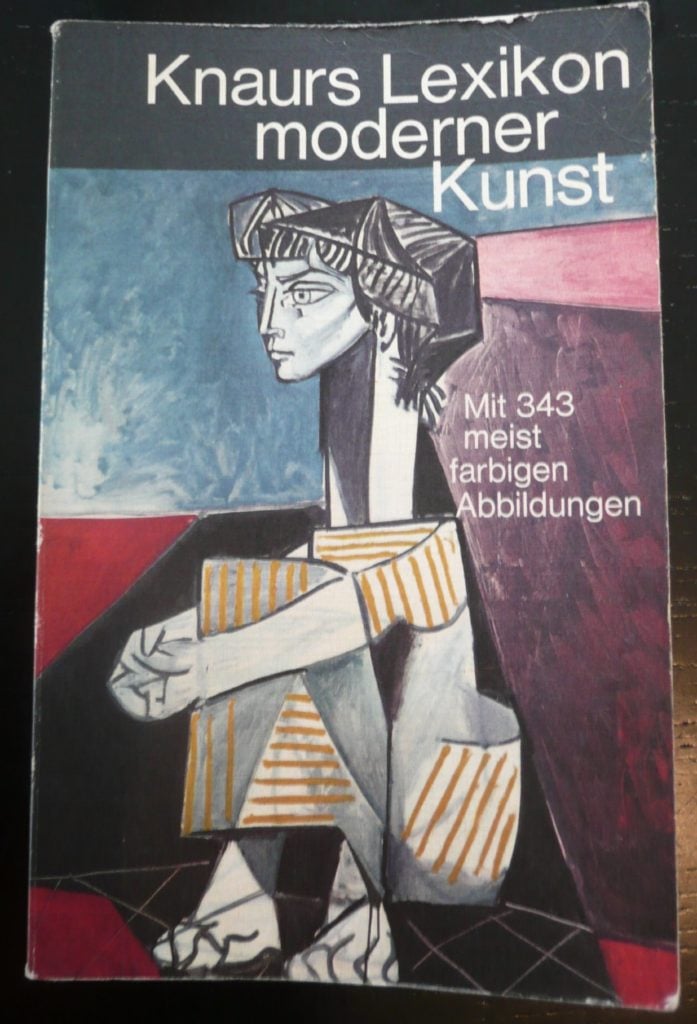

I doubled the money in one trip. After that, I traveled back and forth for three years or so while I was studying, and I did quite well. I made some money, and I had an inventory of prints, like Manessier, Bissier, Kokoschka, Hartung, Soulages, and other artists who were active in Paris at the time. You know, they called it l’Ecole de Paris. And then I started to think it was embarrassing to go to see people and unpack the prints and then show them at their home, and so I thought, “I must have a gallery.”

At the time, there was only one gallery in Hamburg, which was Brockstedt. Other than that, there were only frame stores that occasionally had artworks. So I opened a gallery, and that was a big success. Everybody wrote about it. My first opening was packed with people. The interest was huge. But there was no merchandise, and no money. People didn’t have any money.

A poster for a show of l’Ecole de Paris artists. Courtesy of the Royal Academy of Arts.

Did you call it Galerie Hans Neuendorf?

At first, I called it Hamburger Kunstkabinett, which signified both the smallness of the operation and was also a nod to Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett, which was my role model. But then I switched it to Galerie Hans Neuendorf, and it’s been that ever since.

Where did you open it?

It was an apartment in the same building where we lived. The first floor had become available, and with the help of my father, who persuaded the landlord to rent it to me, I was able to get it. Then, with my brothers, we painted the walls. Suddenly I had the rooms—but I didn’t have any merchandise, except for a few prints. So I started showing contemporary Hamburg artists, and that was very interesting. I got involved, working with the artists, and that’s how I started.

And you represented them, like a modern gallery?

No, I just showed them. They were really happy that someone took an interest, and it was very business-only. “Representation” was something I didn’t even know existed. And so when I showed them, I tried to sell their work, and I even sold some of it.

So was it successful?

Yes, it was successful, but very slow. It was successful on a very, very low level.

How old were you at this time?

I was 23 or 24 when I started the gallery, and by then I was getting a little bored with the Ecole de Paris. I was even in the process of writing a book about the end of art.

Really?

That was the big thing then. Hans Sedlmayr was an art historian who specialized in cathedrals and who was teaching at the university, and I was remember going to one of his lectures there. It was in the air that art was decadent, and it couldn’t go on like this—which is pretty much what I’m feeling again now. So I began to write this book with my friend who was the son of the architect, and we never finished it, of course. But we did get bored with the Ecole de Paris, so I stopped going there and buying these things. I thought, “If this doesn’t get any better, what do I do?” And then news arrived from America about Pop art.

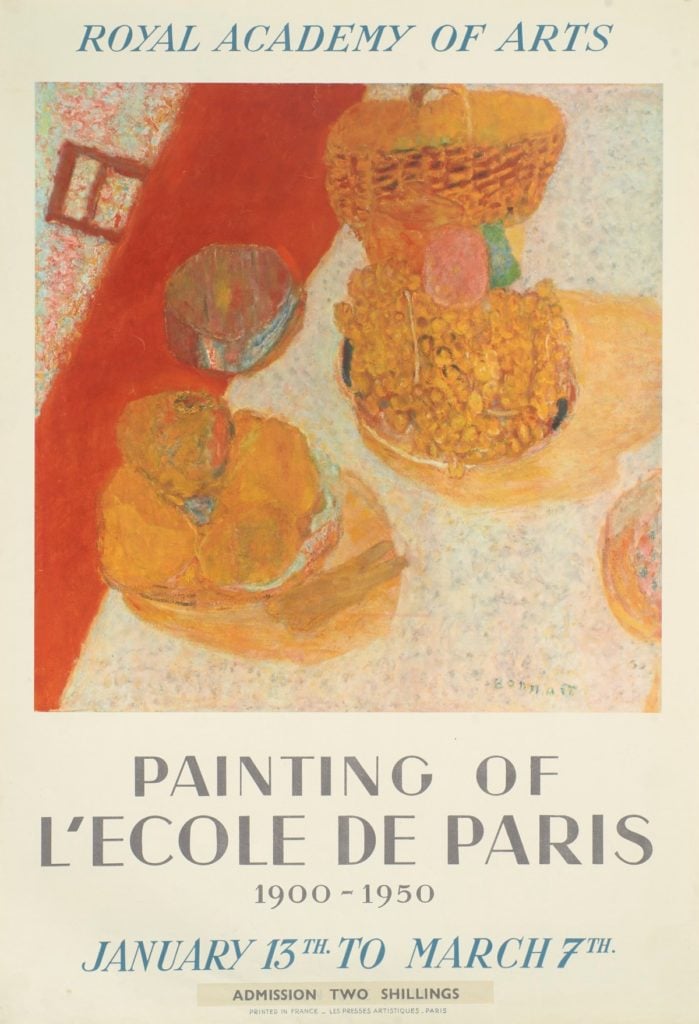

The Romanian-born art dealer Ileana Sonnabend (1914-2007) in her gallery in front of a large-scale painting by AR Penck. Photo by Michel Delsol/Getty Images.

How did you hear about it?

Well, it was some article in magazine that went around. And then there was talk of a gallery in Paris, Ileana Sonnabend. So I immediately went to Paris and talked to her, and that led to the first Pop art show in Germany, with paintings by all the great masters.

How did you manage to bring these artworks into Germany?

That was kind of adventurous. A friend of mine had a trucking business, and for deliveries in town he had a small delivery truck with only canvas around it. He lent it to me, and it took three days to drive to Paris because the thing was so slow. When we got to Paris we went to Ileana, because she had promised me the paintings, and we rode away with these paintings on a rickety truck. She didn’t blink an eye. She just thought it was perfectly normal.

Did she sell them or consign them to you?

She consigned them—I didn’t have any money to buy the paintings. She asked $10,000 for a Jasper Jones—I thought it was insane. She asked the same for a Lichtenstein. She had protective prices that nobody would pay, just for insurance purposes, and she actually didn’t want to sell any of the things. But she gave me some offset prints, and I sold them for 200 marks, and that’s how I made a little money out of it. But I didn’t sell any of the paintings. There were three Rauschenberg paintings, three Jasper Johns paintings, two or three Warhols, including Four Marilyns, and two Lichtensteins, one of which was I Know How You Must Feel, Brad.

This would be around $1 billion in art today.

Easily, yes.

So you loaded them on the truck and drove them back?

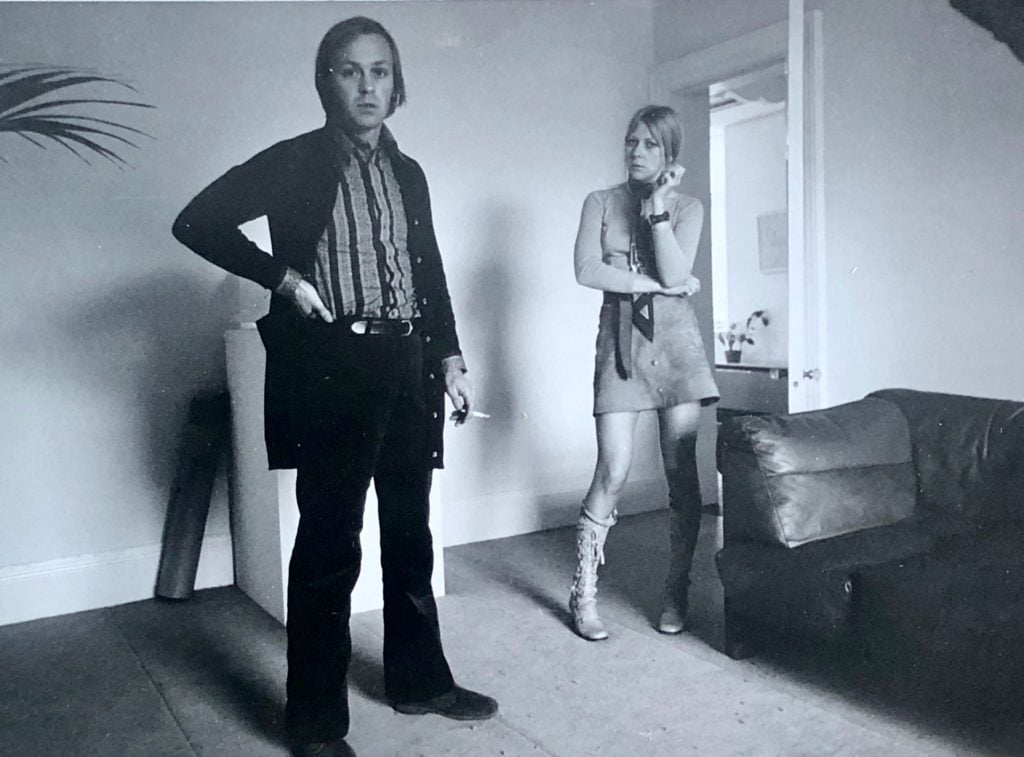

My brother was with me, so he was sleeping on an air mattress in the back of the truck. And then in the morning we drove back to Hamburg. It was a long trip, and we were accompanied by a girl, Florentine, who became the mother of Jacob [Pabst, today CEO of artnet]. She was in Paris with a family, learning French, and she lived in the same building, and she wanted to join us on the trip. She thought it was so exciting.

How romantic.

That’s how the paintings came to Germany. It was a big success, in terms of press. They were joking about it, and all of that. They didn’t take it seriously. But, in particular, the customs officials didn’t take it seriously.

Did you have trouble getting the art into the country?

It was difficult. We had to fill out endless papers. The only way we could make it look like it wasn’t merchandise was to say that I had painted it, and they commiserated with me, saying, “That’s very odd.” They were laughing that we thought this was art.