As one of the last remaining museums in the United States to also operate its own school, the Art Institute of Chicago occupies the heady responsibility of teaching the next generation of artists and specialists at the same time as the institution is itself forced to learn how to navigate the complex realities of a shifting art landscape. As director and president of the museum, James Rondeau has eagerly adopted the role of the Art Institute’s top student, trying to learn how to connect with Chicago’s 21st-century art audience—while at the same time, when it comes to further building out the museum, anticipating the needs of a 22nd-century art audience.

Rondeau is in the enviable position of being able to plan for this future in a meaningful way, because, over the past year, he has helped bring in $70 million—including $50 million in unrestricted funds—together with the massive Edlis/Neeson Collection, which has instantly helped propel the institution’s Modern and contemporary holdings to the front ranks of American museums. And, at the same time as he is planning for the future, he is also investing in it, working with outside organizations to help train a more diverse pool of art experts who could work at the museum in years to come.

Here, in the conclusion of a two-part interview, artnet News’s Andrew Goldstein spoke to Rondeau about how he is reshaping the 126-year-old museum he oversees and why some things that other directors see as liabilities he views as enormous assets.

The Art Institute of Chicago as seen in 1946. when an exhibition of paintings by Hogarth, Constable, and Turner was showing. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

The Art Institute sits in an incredibly diverse city in the middle of a tremendously polarized country. One thing that the museum has been doing is working with with a number of organizations and grant programs like the Mellon Undergraduate Curatorial Fellowship Program to provide opportunities to young people of diverse cultural backgrounds. Can you explain the thinking behind these programs, and the need for them?

When the trustees voted in the 1890s to change our name from the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts to “Institute,” it actually was super willful and self-conscious to position it as an educational resource. We’ve always been a teaching and training organization. And one of the things that we realized will help ensure our ongoing relevance is that we need museum professionals who more accurately reflect the cosmopolitan city we are in.

About eight years ago, we embarked with Mellon and four other partner museums to work with undergraduates who had declared an interest in art history or a discipline that could bring them into museum work, be it museum finance or conservation science. It’s a broad umbrella, bringing individuals from underserved populations in the museum field to Chicago to help them understand the business. Then we track four people in that large group through a fellowship program, and we stay with them as long as they stay in the field, so through MA and PhD programs. Now we’re seeing our first individuals entering PhD programs, and then we’ll help to place them in museum work.

So they’re getting jobs?

They’re getting jobs. One was just a fellow at the National Gallery. And that cohort is mentored for their entire journey, so that means working with them on writing skills, resume-building, professional networking, and providing support for conference travel. As I’ve learned from Mellon, we don’t say we’re building pipelines—we’re building ladders.

Another part of this was recognizing that internships at the Institute can be exclusionary, because the majority were previously unpaid, so it was a self-selecting population. Now, with help of the Diversifying Art Museum Leadership Initiative, supported by the Ford Foundation and the Walton Family Foundation, we’re trying to change that. Currently I believe we’re cresting near 65 percent of our internships being paid with industry-standard wages, not just a kind of intern stipend, and we’re dedicating separate resources specifically for recruiting candidates from underserved minority populations.

These initiatives are manifestations of systemwide goals. In the last few years, we’ve begun providing free admission to Chicago teens, and we’ve quadrupled the number of teens coming to our museum. There are also membership cards in every Chicago public library, so anyone can check out a membership card and come visit for free. Thirty percent of people visit our museum for free. I wish we were free for all, but we’re trying systematically remove barriers for access.

Mellon Chicago Objects Study Initiative students at the Art Institute of Chicago. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

How involved are you personally, as director of the museum, with the School of the Art Institute?

The school is older than we are. When our first primary home opened 125 years ago, all we had in the museum were plaster casts from antiquity for teaching. It’s this wonderful image, where in the 1890s you would walk in and see the Winged Victory of Samothrace. “Oh, that’s in Chicago?” No, it was a plaster cast from the Louvre. In other words, our origins are profoundly rooted in the school, and in teaching.

Today we operate along two separate business models, reporting up to one board. There are two presidents—I’m president of the museum, my colleague Elissa Tenny is president of the school—and we maintain independent businesses and independent staff, but we share things like HR, legal, and IT. It’s an unusual business model, but there’s this dynamic creative community in our galleries all day every day, and that makes it something special.

And, of course, we’re one of the last museums [in the United States] that have maintained their own school. Boston gave their school to Tufts. The Corcoran’s closed. It’s down to us and the MFA Houston, with their Glassell School of Art, to be the remaining places where the art museum and the art school co-exist.

Right now the discourse around identity has become a huge current in contemporary art, relating to everyone from artists making it to the curators showing it to the museum directors hiring those curators. I was looking through the courses at the Art Institute and it’s a sign of the times, perhaps, that the school offers classes in “Economic Inequality & Class” and “Race & Ethnicity” and “Gender & Sexuality” at the same time as “Printmaking,” “Illustration,” and “Game Design.” It suggests that those concerns are seen as equally important for art as the techniques used to illustrate them. I wonder, how do you see this kind of educational mission evolving in tandem with the museum’s mission? Is this something that you guys talk about in those board meetings?

I don’t take any responsibility or credit for that quite brilliant list of course offerings in the general curriculum plan. This school has been known for being very progressive and methodological while at the same time maintaining a really strong core of training in painting, sculpture, printmaking. In the same way, we have maintained our core at the museum as well. We’re still delivering major exhibitions, scholarly volumes. We’re still in the business of showcasing silver and 15th-century embroidery. But we recognize that we are as much about experiences as we are about objects, and we strive to reflect that in our programming, and even, someday, in architecture.

A tour group viewing Georges-Pierre Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte—1884, 1884–86, at the museum. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Earlier this year there was some reporting on the difference between the so-called “Twitter electorate”—the vocal percentage of people online who tilt toward the political extremes—and the more moderate actual electorate. Your museum welcomes 1.7 million visitors a year, smack in the middle of America. What percentage do you think these issues of identity are relevant to, as opposed to just seeing the Grand Jatte?

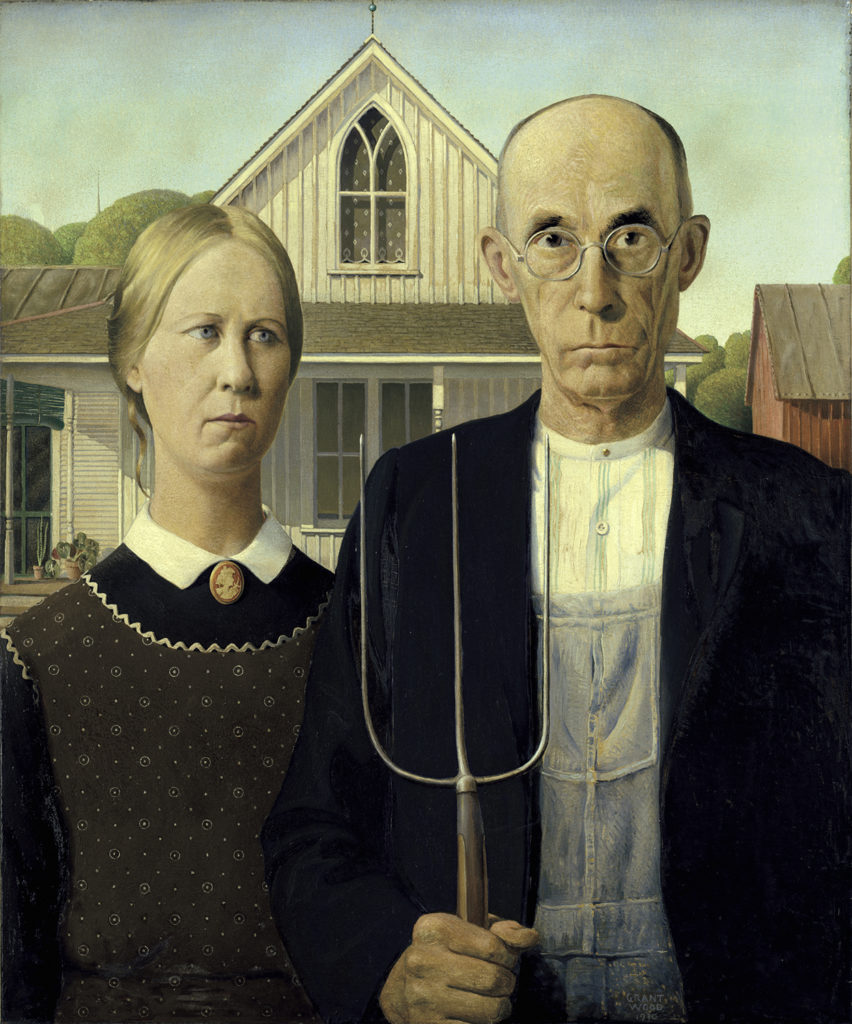

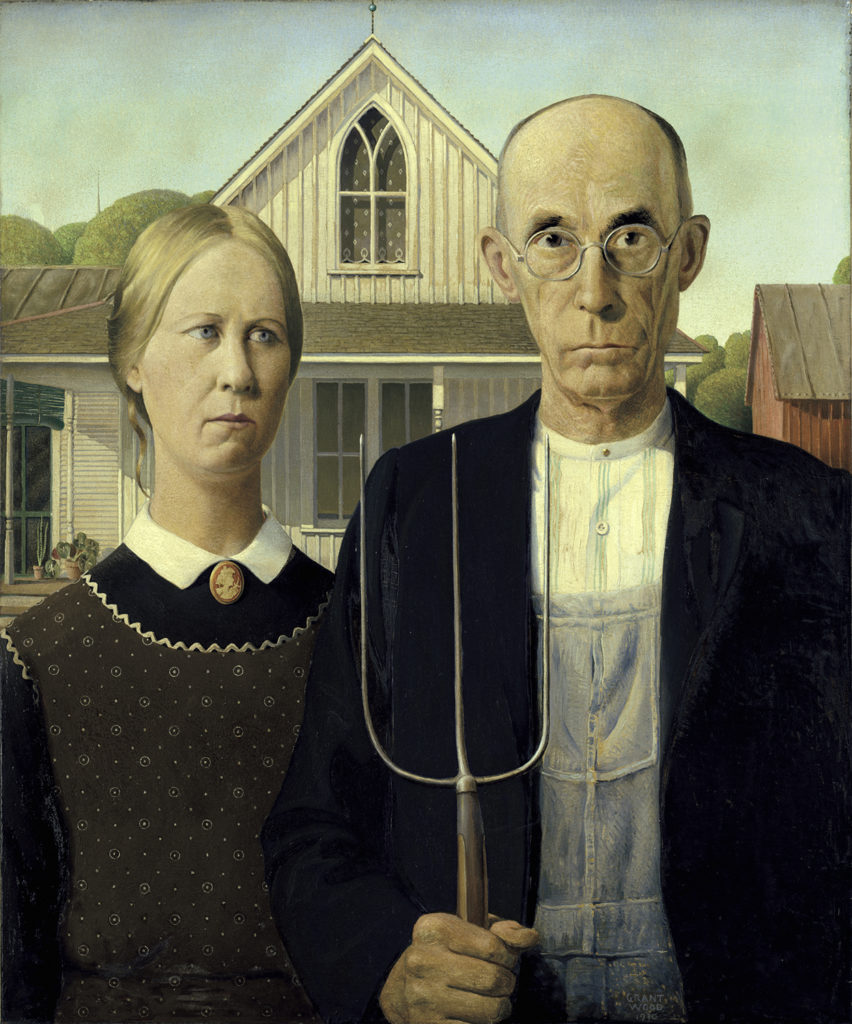

Some individuals who visit our museum are expressly invested in understanding their own cultural relevance, to identify makers who look like themselves, who identify stories that are resonant to connect with a dynamic urban city. I think others come in only to see La Grande Jatte or Nighthawks or American Gothic, but they’re actually going to experience this inclusion by osmosis, since it’s become the default for our galleries.

You’re seeing the Taos school along with Ashcan. You’re seeing a concentration of Cassatt, of course, but you’re also seeing Marguerite Zorach along with William Zorach. You’re seeing African American makers in the 19th century and you’re seeing white makers represent African American life in the 19th century. There is no longer an inclusion corner.

It’s like when I talk about digital initiatives and younger people on my staff pull me aside and say, “James, we actually don’t need to use the word ‘digital’ anymore. You can tell us if something is analog, because that would be exceptional.” We’re simply at a point where the only credible way to embrace storytelling is to have this broad lens.

When we were making the decision about postponing the Mimbres pottery show, we had a meeting with the executive committee on our board, which, by the way, is one-third individuals of color, with three women of color out of the nine executives. That means conversations around inclusion are deeply resonant for our executive committee in ways that they wouldn’t have been five years ago. But a board member said, “We understand. We totally support this decision. But it’s a slippery slope, James. Where does it end?” And immediately I said, “You know what? It’s actually not a slope. We’re not sliding backwards into some like morass, like we have no agency. We’re actually on an incline.” Inclusion work is an incline, and we’re making deliberate exerted steps to get to the next plateau. So, where does it end? Never. It actually will never end, and that’s exactly how it should be.

Grant Wood’s American Gothic,, 1930. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Do you ever hear from any more conservative constituencies who argue that by giving so much visibility to new narratives that you’re displacing some kind of classic American narrative? I mean, you majored in a subject called “American Civilization” at Middlebury; today that’s not even a department anymore. We know that there are lots of people in this country who feel growing diversity threatens to displace them. Does anybody ever vocalize this to you or the museum?

No, because it’s not either/or, it’s both/and. We still maintain these extraordinary focused pockets of expertise in very traditional ways and there are all these incredible silos in this institution, where one individual can spend 15 years studying Soviet posters.

At the same time, there are institutions that I think are in the midst of remaking themselves wholesale. The work that Anne Pasternak is doing with her team in Brooklyn is amazing. We’re learning from a lot from them. I think Chicago is still in a place where we understand that we’re trying to sustain multiple identities and take responsibility for the past, present, future tense of our institution.

Speaking of the future of the institution, you have been had truly remarkable success in bringing in enormous donations. Not too long ago, you secured the Art Institute’s largest-even unrestricted gift—$50 million—from your board members Janet and Craig Duchossois. Another impressive recent gift was a $20 million targeted donation that board chairman Robert Levy and his wife Diane gave toward operations and acquisitions. You also won for the museum the $400 million donation of Stefan Edlis and Gael Neeson’s renowned collection of Modern and contemporary art. What is your fundraising secret?

It’s not a secret. It’s Chicago. This city has always been profoundly philanthropic, and I think our supporters understand that supporting the museum also means helping to define the future of our city. The gift from our board leaders, Janet and Craig Duchossois, is about looking at spaces in our long-term master plan that actually have no assigned function. We don’t yet know what the museum experience is going to look like in the second half of the 21st century, but we do know it’s not going to be calling out for a new hall of arms and armor. This is something that we can’t possibly understand yet, but we need to invest in architecture that could support whatever the future might bring us. So when Janet and Craig said that investing in a vision for the future is what appeals to them, it was a down payment on future excellence. That’s inspiring.

A view of the Art Institute of Chicago’s Modern Wing as seen from Millennium Park. Photo by Charles G. Young, Interactive Design Architects, courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

There’s this trend in museum architecture these days that I like to call the “future box,” where architects and museums are uniting in a kind of Hail Mary to build something to accommodate whatever art might be coming down the pike 10, 20, 30 years from now, and generally what they come up with—as with the Shed, or with MoMA’s new central gallery—is a giant, column-free space. The thinking seems to be, if you build it, the art will come. Is that something you are interested in for the Art Institute?

I don’t see any of our peer institutions making similar plans to what we have in mind. Places like MoMA and the Shed are very much devoted to Modern and contemporary. To have an institution that is actually going to bring you stories from the Bronze Age as well as the 18th century and Modern and contemporary, that’s like none of our peers.

Shifting to the Edlis/Neeson gift, one of the stipulations that Edlis and Neeson had in donating their collection—which features masterpieces by such artists as Jasper Johns, Cy Twombly, and Warhol alongside definitive works by Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, Jeff Koons, and others—is that they want to ensure it will remain on view 50 years. Edlis has called the terms “the deal of a lifetime” because it ensures the works will not be going into storage anytime soon. The fact is, no one likes having art in storage—and museum storage has actually become a surprisingly lively topic in the field, because it’s very expensive to maintain and it’s not a very efficient use of space or money. Over the past year, the museum bought $26 million worth of new art acquisitions, and deaccessioned other objects worth $6 million. What do you think is the museum’s responsibility in terms of right-sizing the collection?

There’s a formulation of museum storage as this cold, dark place, like in the last scene of Raiders of the Lost Ark, where it’s a kind of absolute entombment. But remember, we have always have been a teaching and training organization—for us, storage is an incredibly dynamic place. The lights are actually on in storage. We have offices and study centers in storage. We have artists from the school teaching classes in our painting storage. So this idea that storage is a resource-straining albatross? We don’t think like that. If you toured our storage, and as you were getting a taxi to leave, I asked, “Andrew, do you think we were able to execute our mission based on what you’ve seen today?” I think you would say yes.

Mellon Summer Academy students at the Art Institute of Chicago. Courtesy of the Art Institute

Based on storage.

Ninety-five percent of my ability to deliver our mission is playing itself out in storage, because a very small percent of what we actually hold in our collections is on view at any one time.

And this conversation that we have too much? Well, one has to be judicious, and, as you say, we have sold $6 million of art. We’re always editing the manuscript—but the notion that we have that manuscript of the collection, so to speak, in storage is not a liability. It’s one of our greatest assets.