The Big Interview

‘In the Art World, Revolution Is in the Air’: Artist Ed Ruscha and Music Legend Jimmy Iovine on How Art Guides Political Change

Iovine commissioned Ruscha to paint a tattered American flag in 2017.

Iovine commissioned Ruscha to paint a tattered American flag in 2017.

Andrew Goldstein

Right now, thousands of voters are casting their ballots for the 2020 US presidential election not in a church basement or school gymnasium, but in the Brooklyn Museum, which has transformed its lobby into a polling place.

As these people vote, they may look up to see a harrowing image: a six-by-12 foot painting of a tattered American flag that seems to be disintegrating in the midst of a stiff wind, with torn bits flying off like apocalyptic confetti. Titled Our Flag, the painting is a vivid representation of the battered state of the country’s unity today, and it’s the work of the great artist Ed Ruscha, a towering figure in American art who is best known for his pop-inflected canvases of words and phrases floating in space painted with the lavish care and illusionistic grace of a Renaissance Madonna. What he is not known for, however, is getting political.

The painting in the Brooklyn museum was originally commissioned in 2017 by the music legend Jimmy Iovine, a longtime friend of the artist whose own creative achievements are equally laudable. A producer who started out minting hits for John Lennon, Bruce Springsteen, and Patti Smith, he then went on to found Interscope Records in 1990, signing the unknown Tupac Shakur the next year. He has since gone on to found Beats with Dr. Dre, sell it to Apple for $3 billion, and then launch Apple Music. Today, he’s retired and stirring up all kinds of good trouble in the education realm.

So what’s the story behind their flag painting, and why does it matter so incredibly much today? We spoke to the two giants of creative industry to find out.

You can listen to a shortened version of this interview on Artnet News’s Art Angle podcast.

Thank you very much for joining me today, gentlemen. So I definitely want to talk about Our Flag, but before that I’m curious, how did you two meet in the first place?

Jimmy Iovine: Well, I don’t remember exactly how we met. Maybe Ed remembers how, but my dad was a longshoreman and worked out with the docks and he used a hook. And I was really wanting to get that hook incorporated into a painting to represent him. And Ed saw it and said, “You know, something about that hook really interests me,” and now I have an incredible Ed Ruscha painting of my dad’s hook, and we developed a relationship after that. Is that close, Ed?

Ed Ruscha: Very accurate, Jimmy. It’s quite a tribute to your father, too.

Can I ask you, Jimmy, how did you first get interested in collecting art, coming from the hip-hop music realm?

JI: I’m interested in great artists of all kinds. I’m actually as interested if not more in the actual people that make art. I’m interested in the work, naturally, but the people fascinate me, and because of great artists I’ve had an incredible life. I’m not an artist myself. I’ve made records and stuff, but not to the extent of someone like Bruce Springsteen or John Lennon, or, of course, Ed.

I’ve always been able to develop really good relationships and support those artists and help wherever I can.

Now Ed, you are “Mr. LA.” You’re basically the poet laureate of Los Angeles and its open highways and striking landscapes. What exactly did you make of this fast-talking Brooklynite when you first met him?

ER: [laughs] Well, I knew that he was in the music business and he had a lot to say. His success in the music business is something to appreciate and to recognize, and a lot of stuff spins around Jimmy and his creations. Plus, on top of that I could see he was genuinely interested in art, in contemporary art, so there was a connection there.

JI: I should say, David Geffen has really influenced me greatly in the art market—as he has in every other aspect of my career. He’s been a friend of mine for 40 years, and he’s such a great collector, and has such great taste. He was really a major, major factor in both my wife and I really taking our collection to the next level.

Of course, David Geffen is a powerful collector of both sides of the country who is really known for being an exemplar of art patronage. So going back, you commissioned Our Flag in 2017, what is the origin story of this painting and how did it come into being?

JI: I’m very fortunate in that one of the first works I ever bought was a David Hammons’s African American Flag. I’m very plugged in to Black America and what is happening within African American culture has been extraordinary to me. I’ve been able to learn so much about life, and I feel that African American culture is the most under-resourced and under-appreciated asset that America has right now. So I had this Hammons flag, and then I went to someone’s house who had an Ed Ruscha flag, Our Flag, but the earlier one, and I saw it and I said, you know, this thing is incredible.

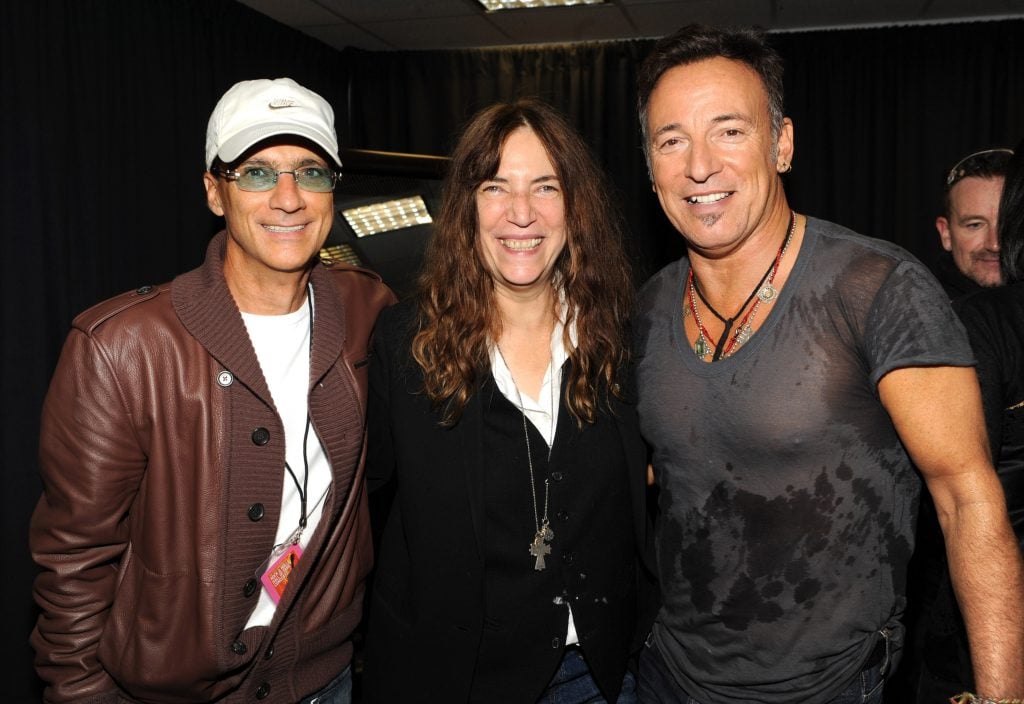

Jimmy Iovine, Patti Smith, and Bruce Springsteen at Madison Square Garden on October 30, 2009 in New York City. Photo by Kevin Mazur/WireImage.

My comp to Ed in the music business is Bruce Springsteen. They are similar in many many ways, and their careers are similar in many ways. Very few artists have amazing, incredible, wonderful third acts in their careers: I think Springsteen’s having one right now with the book, the play, and this new work that he just put out, it really captures what it feels like for him to be at this place in his life right now. It’s very powerful. But in my opinion Ed has done work as powerful as this [Our Flag] but this is one of the most important things he’s done, and he did it at 80 years old. So I said, you know what, he’s the guy to make a painting. I called him up, and I said, “Ed I’ve gotta have a Ruscha flag,” and he said to me, “Only if I can make it the way I feel about America right now, today, and that is tattered.”

So all my experience just kicked in and I thought, this is a great artist with a great idea, and said, “Man, I’m in” and hung up the phone before he could change his mind.

So Ed, what exactly did you make of that?

ER: Jimmy offered me enormous freedom with the project, I’m not sure if that’s an odd word or an adept word at this point. I’ve done four or five other American flag paintings and they’ve all sort of been the hearts and flowers version, very positive rendition of this flag. But I saw something different with this one. I saw a president in our country that I felt had absolutely no good will towards anyone who didn’t drink his Kool-Aid, and I could envision a painting that was like pieces of the USA scattered to the wind. It offered me a great challenge to be able to paint something like that, because it was actually lots of fun, I’ll tell you that!

But anyway, we’re going to need more than Betsy Ross to put that thing back together, but I think we’ll do it.

So this was in 2017—what exactly was the climate in the country at this time? What was going through your head at that time, Ed? Were you thinking for instance about the deadly Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville?

Well, let’s see, Charlottesville was a little after I painted this picture, but I could tell that there was unrest and discord in America that was brought on by this administration.

I kept thinking we should let Mark Twain speak for us when he said “politicians and diapers must be changed often, and for the same reason.”

JI: That’s great, paint that for me, Ed!

ER: The metaphors are there. I could see tyranny and dark skies ahead with this administration, it looked dangerous. Hence the black sky in the background.

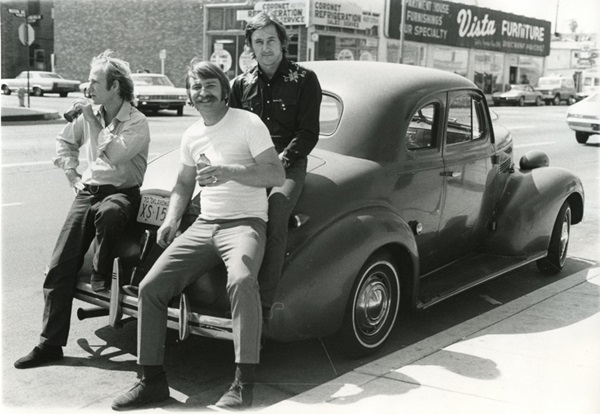

Joe Goode, Jerry McMillan and Ed Ruscha, with Ed’s ’39 Chevy, 1970. Courtesy of Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica, California.

If there’s one word that is used to describe you, Ed, it’s “cool.” Both you and your work have epitomized California Cool since the days when you were a part of the “Cool School” at the legendary Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles. The science fiction writer JG Ballard wrote that you have “the coolest gaze in American art,” so I have to ask, does Donald Trump make you lose your cool?

ER: When I consider that here’s a person with no redeeming social value, which I guess defines him as being pornographic, yes. I think the way we can look at it is that this guy’s a firehose of vulgarity, and we’ve got to change it. Voters, please rescue us, let’s get on with it!

In December, you’re going to turn 83 years old. You’ve been a witness to so much change in America, how do you think Trump stacks up to the boogeymen of America’s political history coming up through today?

ER: He is a person of unbearable disgust, and I can’t put it any other way. He doesn’t really fit—he’s in his own category. When you bring to mind all of the presidents in the United States, he’s off by himself.

So Jimmy, in your mind, since you commissioned this painting back in 2017, and now it’s just a few days before what very well might be the most important election of our lifetime—how has the meaning of the artwork evolved for you?

JI: To me, art is about capturing or creating the zeitgeists. I come from music, but I can tell you there is no musical artist that has captured the zeitgeist like Ed did with this painting. It is mind blowing how he saw and created this… it’s lightning in a bottle. What he has captured for the country and for the world—because as you know this painting was in the Tate last year.

Very rarely does something capture the moment in this way. Neil Young’s “Ohio” captured the moment of Kent State, there was music about Vietnam, there are some things that have been captured. But as far as art is concerned, I would love for someone to show me something more powerful than this painting of what’s going on in our country right now.

You mentioned Bruce Springsteen earlier, and about a decade ago, in 2001, he came out with the song “American Skin (41 Shots)” which was a very powerful political song about the police killing of Amadou Diallo. You’ve said that visual artists have stepped into this kind of place within the culture that musicians used to occupy when it comes to galvanizing society and really impacting people with a sort of anthem. Why do you think that is?

JI: What’s starting to happen in music, thank God, it’s about time, is that some of these young hip-hop artists are starting to step up, especially in this past year, and really do some good stuff. Kendrick Lamar and DaBaby are good. But, having said that, in the art world revolution is in the air, and you can really feel it. The pain of what is going on right now is coming through for me, particularly within the African American community.

Would you agree with that, Ed?

ER: Oh yeah, I see it. It’s kind of like a rolling thunder where artists are really coming forward. We’re seeing more and more and it’s really inspiring to see this especially with the fact that there is such a barrier to certain people in this country. Because of the way we’re living now in this administration it’s starting to change.

Your painting is in the Brooklyn Museum, and that same institution became a rest stop for Black Lives Matter demonstrators marching in protest against racist police violence this summer. What do you think is the role that museums should be playing in politics right now? What’s their function?

ER: It is inspiring to see this combination of a painting like Our Flag, and it’s very cozy to be in a building that also happens to be a polling site. It’s almost a cultural clash in a way, and yet I see a real opportunity and some hope for the future.

And this is not the only way that you’ve been entering the political fray this year. In fact, you’ve contributed artworks to a number of democratic fundraisers, including Artists for Biden and the People for the American Way. Is this kind of engagement a new thing for you?

ER: I’m kind of surprised myself. It’s probably the most outspoken political position I’ve ever taken as an artist, and we know how old I am. The poster you’re referring to for the People for the American Way fundraiser is called EE-NUF! And it’s a fragmented photograph of the flag with giant letters spelling EE-NUF, “enough.” It could’ve been too much, but I just felt that it was a statement that needed to be on a poster.

It’s a very powerful poster. The words and flag are ringed by slogans like “Bye Bye Roe vs. Wade,” “Kids in Cages,” “Gateway to White Supremacy.” What has the reaction been like to it so far?

ER: I’ve seen them posted up here and there. For me, I’m just a rattlebox of emotions, like bolts in a blender, and things just come out of me. I can’t always explain it, but every so often there are social problems that come about and must be addressed.

It makes me wonder, do you believe that art can change the world in a political sense? Or do you believe that art can be sold to make money to change the world in a political sense?

ER: Probably a combination of all of it. Art gets people’s attention, and it’s a part of our culture. There are so many artists with so many statements, and some people have the notion that everything has been said and so there’s no more new art. I just can’t subscribe to that, I don’t believe that it’s true. Every day you see new work, hear new music, read new literature… it is a wellspring of activity that I hope never stops.

And Jimmy, I’m curious to hear your take on this? Do you think art can change the world, or that art can make money to change the world?

JI: Money is an afterthought of art. Art existed before there was money, and, you know, artists deserve to make a lot of money. They deserve to make most of their money. A lot of times within the art and music businesses that’s not the case, but it’s starting to change. It is art that reflects the person who is translating, like Bob Dylan, for instance. He spoke to all of us, and he spoke for all of us in the 1960s and 1970s. And Ed is that kind of person too—someone who can take the time, the specific moment, and translate it into something we all find beautiful. No painter that I’ve met says, “I’m going to do this to sell and make money.”

On the flip side, we all know too well how enormous a role money plays in politics, and how important it is to have progressive leaders in the business as well as the political realms.

And now Jimmy, you and Dr. Dre gave $70 million to the University of Southern California a few years ago to create a new academy where students can work toward a degree that combines arts, technology, and business. You’ve said that you think this kind of hybridized training might yield the next Steve Jobs, who is of course the epitome of the Renaissance combination of creativity and real-world skill sets. How do you think the knowledge of art, like the kind that Ed creates, can help people be more effective in the world of business and politics?

JI: Art is about the explosion, and the impression, and the emotion, right? So if I’m building something in tech, I want the engineers to give me that feeling in the tech, and that’s what Steve did. I got to know him a bit, and he was just looking for that emotional impact. He was an enormous Bob Dylan fan, an enormous Beatles fan, and he was always looking to get that cultural impact out of his technology. So it is all related.

You look at these companies now where AT&T, of all companies, is buying a media company. People have to learn how to speak both languages. Like Doctor Doolittle had to learn to talk to the animals. So if you want to speak to each other, that’s what we do at our school, and we’re going to go into South Central Los Angeles to build a high school that teaches kids both languages.

On the other side of the coin, Ed, do you think that a knowledge of business and technology can make people better artists?

ER: We’re living in a more or less prosperous time, with the exception of the coronavirus, things are still rolling along, and people have not lost interest in art. That’s pretty good, Jimmy—speak to the animals like Doctor Doolittle.

Jimmy Iovine and Ed Ruscha in Los Angeles, California. Photo by Michael Kovac/Getty Images for CORE Gala.

So to get back to Our Flag, Jimmy, you’re a famous collaborator who’s worked with everyone from Eminem to Lady Gaga—everyone who has ever moved the needle in music. Would you say that your relationship with Ed is a collaboration?

JI: It’s not a collaboration in the painting, but I try to be an inspiration and a cheerleader, and if I throw a little thing in there that sparks something, I’m proud. I said the word “flag,” and then he said a torn flag. I mean, we know where the weight of that conversation is, but I feel good about my little part.

Same question to you, Ed. Would you say that your relationship with Jimmy is a collaboration?

ER: Well, I can say this, I’m not sure that this flag would have materialized in my life without Jimmy Iovine. You have to have a little trigger here, things happen, cause and effect. It’s talking to the animals.

JI: It’s such a gift, man. It’s fantastic. I have to say, too, being in the Brooklyn Museum is so cool for me, I’m from Brooklyn and I know that neighborhood so well. I went to high school in that neighborhood, and what Anne Pasternak has done there is just extraordinary.

It’s amazing that the work will have such an impact on all of the people who are going there to vote. When they walk in to cast their ballots, they’re worried about the future, and they can look up at the flag and know they are not alone. How do you see the legacy of this painting? How do you think people are going to be looking at it 10 years from now?

ER: Maybe 20 years from now, people will say “Oh that painting looks like it represents something that happened decades ago,” and that’s fine with me.

JI: Again, it’s like a song. It captures the moment, and Ed Ruscha has captured this moment in my opinion, better than any other art form has. I’m looking for Trey Parker to write the Trump Broadway play—I think that will also capture the moment, but as of now, Ed Ruscha owns it.

So I want to ask, if there is one message that you could put out into the world right now, what would that be?

ER: There are a lot of question marks out there in the future, and I always look for things that are out in the future, because heck, that’s where we’re going to spend the rest of our lives.

JI: My biggest problem with this administration is what is going on with race. It’s the most important thing in my life right now. I would say simply that prejudice is absurd and ignorant, and why we can’t swallow that and take it in is mind boggling to me. So if I had one wish right now, I wish that racism would end.

ER: Amen.