This story is a collaboration between artnet News and In Other Words.

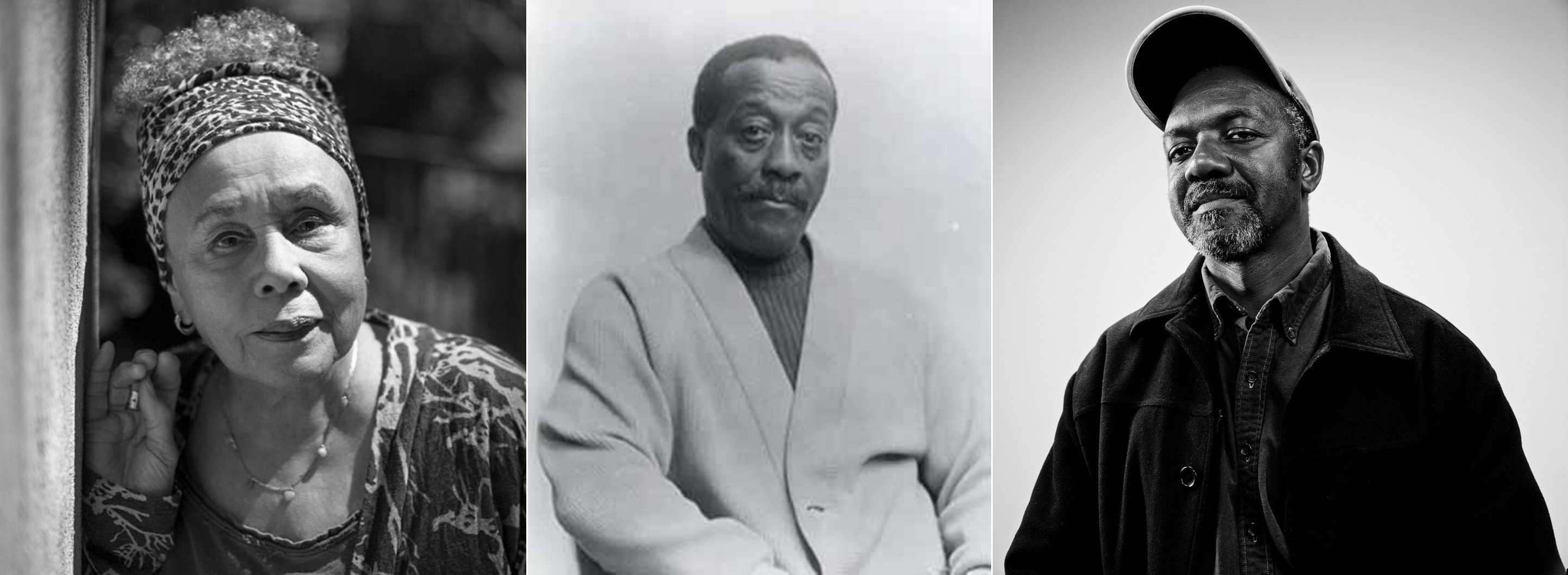

Using data to examine how the representation of African American artists has evolved in American museums and the global art market over the past decade can only tell part of the story. In reality, every artist has a unique trajectory. Below, we consider three artists from three different generations and their divergent paths to market recognition—and the history books.

Norman Lewis

In the photograph, a group of smartly dressed men and women sit around a long table scattered with bottles of beer and bowls of pretzels. They are mainly artists—including Ad Reinhardt, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, and Louise Bourgeois—and they are having fervent conversations about their work. They settle on a name, “Abstract Expressionism,” for the kind of art some of them produce.

The photo documents the Artists’ Sessions at Studio 35, New York, in 1950. Among the sea of white faces is the young African American artist Norman Lewis, a pioneering painter who started his career producing works of social realism before moving towards an abstraction that he would ultimately, many years later, fuse with social commentary.

Installation view, “Procession: The Art of Norman Lewis.” Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

He found great success during his lifetime. His work was exhibited at major museums including the landmark 1951 Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. In 1956, he was one of 36 artists selected to represent the United States at the 28th Venice Biennale.

Despite this, he was not included in the famous LIFE magazine photograph of the “Irascibles”; he was not mentioned in any of the major books about the period; nor was he the focus of a monograph. And he was not the subject of a major museum retrospective until 2015—36 years after his death. Lewis “didn’t make a living as an artist—he had to teach,” says Nigel Freeman, the director of the African American art department at Swann Auction Galleries.

Unlike the majority of his white peers—many of whom left behind deep-pocketed estates—Lewis does not have a dedicated foundation or catalogue raisonné, so “it’s harder to establish or confirm a value for him when there isn’t an accounting of how many paintings he made in his lifetime,” says gallerist Alexander Gray.

Norman Lewis, Untitled (1956). Courtesy of Swann Galleries, Inc.

While fellow Abstract Expressionist Jackson Pollock’s auction record stands at $58.4 million (for the 1948 canvas Number 19, which sold at Christie’s New York in 2013), and Lee Krasner’s—who, it should be noted, also lags considerably behind her white male peers—stands at $5.5 million (for Shattered Light from 1954, which sold at Christie’s New York last year), Lewis has yet to pass the $1 million threshold. His auction record is $965,000, set in 2015 for a 1958 geometric abstract composition that had been unknown and unrecorded before it surfaced at Swann. Over the past decade, a total of $7.2 million has been spent on his work at auction, far less than many of his contemporaries.

Still, the wheels are turning—slowly. Nine of Lewis’s top ten auction results have been recorded in the past five years. In April, an uncharacteristically bright abstract composition from 1956 nearly tripled its high pre-sale estimate, selling for $725,000.

Norman Lewis, Processional (1965). Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York.

Much of the recent market interest followed the major survey of Lewis’ work at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 2015—an exhibition that Roberta Smith, the co-chief art critic of the New York Times, described as a “welcome opportunity to assess the rich and varied path of Lewis’s art.”

Increasingly, Lewis’s reputation is being restored to its rightful position—and his work displayed in proper context. Now, more than 60 years after it was first shown during the Venice Biennale, Cathedral lives at Tate in London, hanging alongside works by Pollock and Krasner. “Tate decided this was a historical priority, went back in time, and used scarce funds to buy that picture,” says the collector Pamela Joyner, who is chair of the Tate Americas Foundation. The history of the work, she adds, says a lot about “where institutions are coming from currently and where they have been.”

Betye Saar

In 2015, the Los Angeles Times asked the artist Betye Saar why she thought no major museum in LA had organized a large-scale retrospective of her work. “I guess it’s always a problem to get recognized in your hometown,” she said. “But they can’t wait and wait because then I’ll die and it’ll cost big bucks. Then they will pay for their hesitation.”

Most major museums, and the art market at large, have been slow to acknowledge Saar’s enormous influence. Institutions in both Los Angeles and New York failed to pick up her traveling retrospective “Uneasy Dancer,” which debuted at Milan’s Fondazione Prada in 2016.

Installation view of “Betye Saar: Uneasy Dancer” (2016–2017). Photo by Roberto Marossi. Courtesy of the Fondazione Prada.

Meanwhile, over the past decade, Saar’s work has generated aggregate auction sales of just $155,140. That 10-year total is 0.8 percent of the amount spent on one work by her peer and fellow assemblage pioneer Robert Rauschenberg, whose Johanson’s Painting (1961) sold for a record $18.6 million at Christie’s in 2015.

Saar’s auction record, on the other hand, is $22,500, set during a Sotheby’s day sale in 2016 for the painted box Personae (1996). Only four other works—all assemblages from the 1960s and ‘70s inspired by a formative early encounter with the artist Joseph Cornell—have sold for more than $10,000 (although her work likely fetches more on the primary market).

Betye Saar, Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972). Collection of Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, California; purchased with the aid of funds from the National Endowment for the Arts (selected by The Committee for the Acquisition of Afro-American Art) Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, CA. Photo: Benjamin Blackwell.

“Part of it is that she’s a woman, and that’s never been interesting to the art world,” says Bridget Cooks, a professor of African American studies and art history at the University of California, Irvine. “And she’s black; but she’s also in LA, so that makes her in the middle of nowhere as far as snobs are concerned.”

To further complicate matters, Saar’s work is consistently representational, an approach that has gone in and out of style; modest in scale, which makes it less likely to attract big prices than large paintings might; and often includes appalling icons of America’s racist history, which she collects from flea markets.

Saar showed alongside Chris Burden at Jan Baum Gallery in Los Angeles until the 1990s and now is represented exclusively by LA’s Roberts Projects (formerly Roberts & Tilton). Yet, for many people, their first encounter with her work was in 2010, when it was included in eight simultaneous exhibitions in California as part of the first region-wide, Getty-funded Pacific Standard Time initiative, which focused on art made in the region and which made clear her importance as a pillar of postwar art.

Betye Saar, Rainbow Mojo (1972). Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

The East Coast is finally waking up to this West Coast artist, who recently turned 92—and shows no sign of slowing down. A major East Coast institution is expected to announce plans for a Saar show soon. Meanwhile, the New-York Historical Society is due to open a solo exhibition of her work, “Betye Saar: Keepin’ It Clean,” on November 12 (through May 27, 2019). Her assemblages also feature prominently in the traveling show “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power,” which opened to rave reviews last week at the Brooklyn Museum. In the spare time she doesn’t appear to have, Saar is working on a comprehensive catalogue raisonné of her 60-year career.

Kerry James Marshall

The sale of 62-year-old artist Kerry James Marshall’s Past Times (1997) for $21.1 million at Sotheby’s in May reverberated around the world, in part because of the voracious bidding war that led the work to sell for more than double its $8 million low estimate, realizing a price almost 900 times more than the $25,000 that its consignor, the Metropolitan Pier and Exposition Authority, paid for it two decades ago. (The fact that the work had a famous buyer—rapper and businessman Sean Combs (aka Diddy)—didn’t hurt, either.)

Kerry James Marshall, Past Times (1997). Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

But Marshall is no one-hit wonder at auction. Past Times is widely considered to be one of the most important paintings produced by an artist now broadly recognized as a modern master. So far this year, all 15 of his works that have come to auction have sold, with five of them achieving prices that now count among his top 10 auction results.

Market interest in Marshall’s work has been building rapidly over the past few years, notably in 2014 when Vignette (2003), a painting of two black figures running, sold during a Christie’s day sale for $1 million—well over its $600,000 high estimate and almost twice what the same work had fetched at Sotheby’s in 2007.

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Painter) (2009). Courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

“There have been waiting lists for decades,” says the artist’s longtime dealer Jack Shainman, who now represents him with David Zwirner. “The list gets longer and longer and his production is quite limited.”

There is not enough supply to meet demand, since Marshall—who often works on a large scale—has a fairly slow production. His galleries also prioritize institutional sales, which means that on the occasion his work comes to auction, bidders chase it with ardor, knowing they might not get another chance.

The length of the waiting list only expanded after Marshall’s wildly successful and critically acclaimed traveling survey “Mastry,” which was organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, the Met Breuer, New York, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, in 2016.

Kerry James Marshall Study For Past Times (1997). Photo: courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Shainman also encourages collectors to resell Marshall’s work through the gallery privately whenever possible, rather than putting it up for auction. When a collector resells a work through Shainman, the artist gets a cut of the proceeds (which is not the case at auction, or with some other galleries). “They get part of the commission we get,” Shainman says.

Later this month, on September 25, the art advisor Joel Straus is selling a study for Marshall’s record-setting work, Study for Past Times (1997), at a Sotheby’s sale organized by the collector and hip-hop producer Swizz Beatz in New York. Straus bought the study from the artist at the same time he bought the finished work for the McCormick Place Art Collection in Chicago. Now, the study is expected to sell for between $900,000 to $1.2 million—around 3,900 percent more than his client paid for the original painting in 1997.

For more from this project, see our examination of museums; our examination of the market; visualizations of our findings; and our methodology.