Art World

Kerry James Marshall’s Met Breuer Retrospective Breaks the Canon Wide Open

The artist provides a “counter-archive” to more than six centuries of black invisibility.

The artist provides a “counter-archive” to more than six centuries of black invisibility.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

It’s official: Kerry James Marshall is the 21st century’s unacknowledged dean of living American painters.

He is not the first major African American artist to receive a full-dress retrospective at a major American museum, of course. That distinction belongs to Jacob Lawrence, who teamed up with the Brooklyn Museum for a survey in 1960. Yet Marshall’s current retrospective, “Mastry,” at the Met Breuer feels like the beginning of something new. (The show is organized jointly by the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, and the Met Breuer.)

Marshall’s paintings, made during a bootstrapping 35-year career, bring together various elements of the culture many thought permanently ripped asunder: Western painting and the black figure, formalism and everyday subject matter, the canon and institutional critique, conventional realism and finger-on-the-pulse cultural relevance. A mere stroll through his present exhibition is sufficient to draw comparisons to the synthesizing gifts of Barack Obama—America’s uniter-in-chief.

At Marcel Breuer’s concrete bunker, Marshall’s nearly 80 works—they include collages, portraits, capsized Norman Rockwell pastorals and painting-within-painting riddles—enact important oil-on-canvas homilies and exorcisms for America’s roiled, divided culture.

Most notably, his oeuvre has given consistent presence to the virtual absence of black bodies in art history’s skewed visual archive. Like a galvanizing Obama speech—say, the one that eulogized the victims of the 2015 Charleston shootings—Marshall’s artworks also perform important triage. They expose, disinfect and cauterize age-old hypocrisies with the precision of a front-line surgeon.

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Painter). Courtesy of the Met.

Marshall’s collected canvases apply the forensic method to dissect what is arguably Western painting’s greatest we-know-whoddunit. Titled “Mastry,” after the artist’s repeated confrontations with the Old Masters, his survey proposes, in the artist’s own words, a “counter-archive” to more than six centuries of black invisibility. To experience this show is to clock something amazing—Marshall has literally taken apart and reassembled Western art history one painting genre at a time.

Self-portraiture, religious painting, history painting, landscapes, nudes, fêtes champêtres, abstraction and other tropes have all been mobilized by the Chicago-based artist to achieve his lofty artistic goal of painterly self-representation. But rather than aspire merely to what scholar Mark McGurl terms “the institutionalization of the anti-institutional,” Marshall instead constructs the foundation for a crucial conversation—one that swirls around the historical invisibility of the black subject and, by extension, the black artist.

Put differently, every one of Marshall’s paintings at the Met answers the following question affirmatively: Has this artist’s effort to paint it black added a new understanding of the history of the medium?

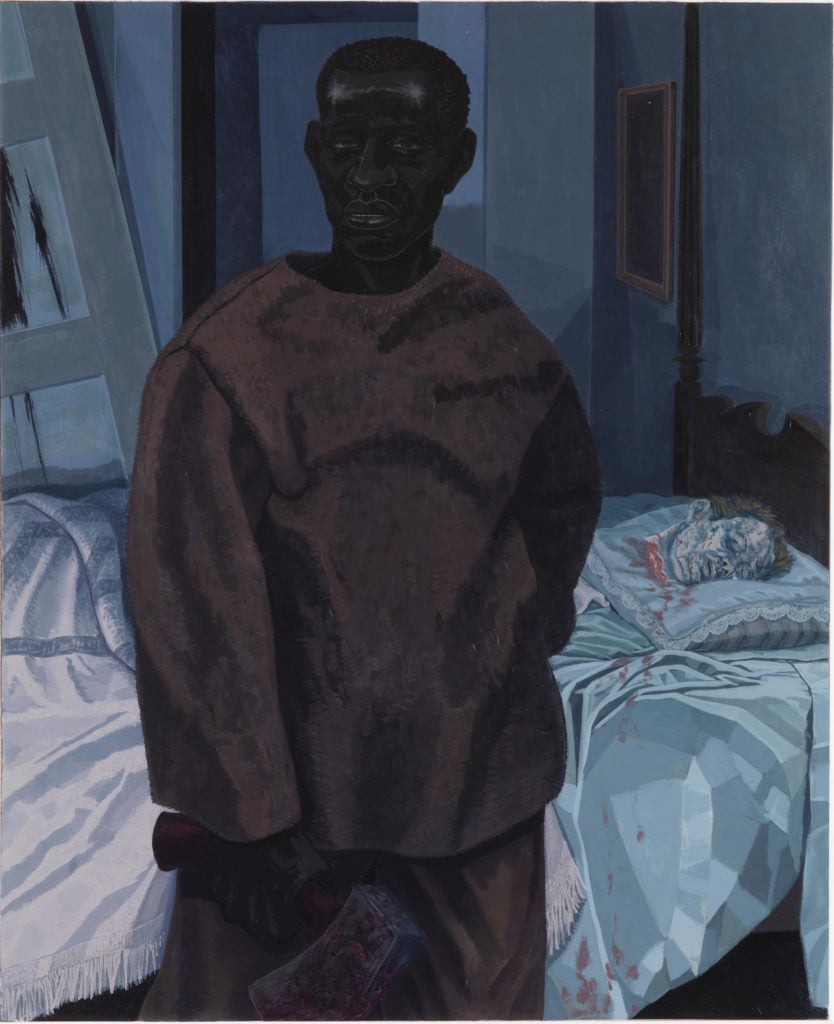

Kerry James Marshall. Portrait of Nat Turner with the Head of his Master. Courtesy of the Met.

Marshall’s own biography looms over his calculated yet thrilling paintings like a troubled inheritance. Born in Birmingham, Alabama, he moved to South Central, Los Angeles, in 1964—just in time for the Watts riots and the opening of LACMA. After studying at LA’s Otis Institute, he lit out for New York and a residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem. In 1987, he moved to Bronzeville, on Chicago’s South Side, where he became a local celebrity after receiving a MacArthur “genius” grant in 1997. The fact that Marshall—whose 1992 painting Plunge sold for $2.1 million at Christie’s in May—has occupied the same house with his family since first moving there provides a glimpse into the ethics this artist also brings to his knotty aesthetics.

Blackness itself—which scientists say “is not a color but the absence of color”—has been wielded by Marshall as both a pigment and a “rhetorical device” from the outset.

What this means in practice is that, since approximately 1980, the artist has painted every one of his figures using exclusively three kinds of black: carbon black, originally made from soot; mars black, made from synthetic iron oxide; and ivory black, fashioned from burned animal bones. Marshall’s point is composite and heavy—to confound the legibility of his figures, while establishing a working analogy between painterly visuality and historical visibility. The enigmas of his black-on-black pictures dominate various Met Breuer galleries—they weirdly harmonize Ad Reinhardt’s “last paintings” and Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man into the bargain.

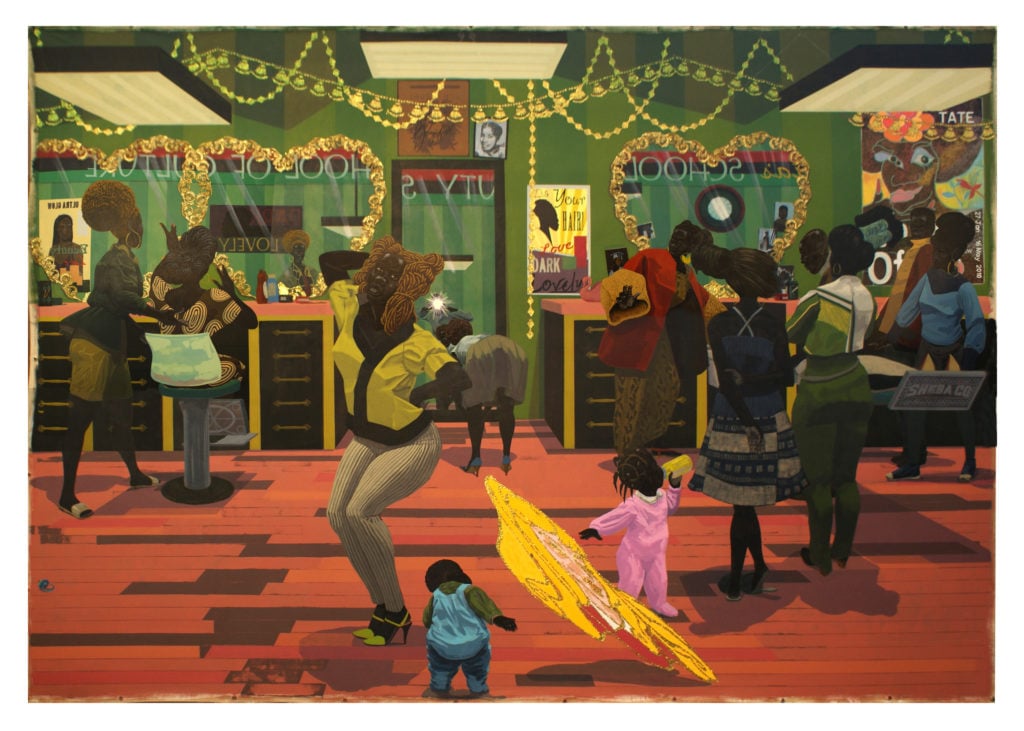

Kerry James Marshall. School of Beauty, School of Culture. Courtesy of the Met.

“Extreme blackness plus grace equals power,” Marshall says by way of formulating an eloquent artist’s statement: “It’s a kind of stereotyping, but my figures are never laughable.”

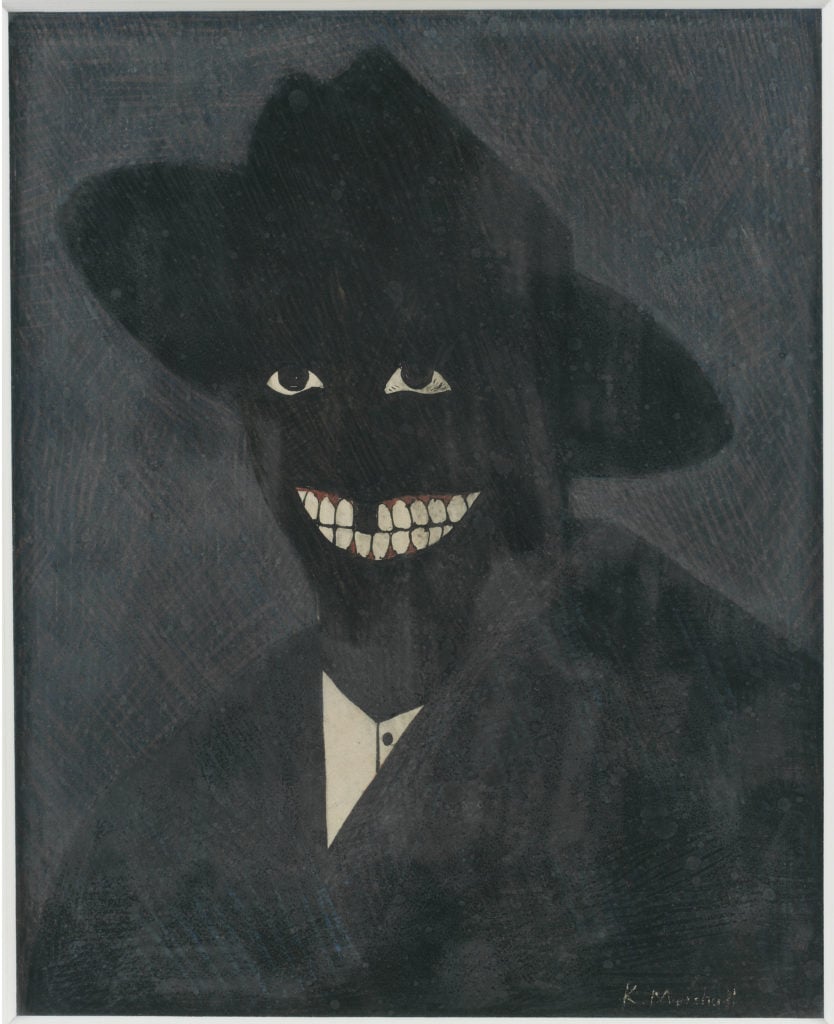

Consider, in this light, one of the show’s most important pictures—A Portrait of the Artist As a Shadow of His Former Self (1980). Painted just two years after Marshall left art school, the picture packs a K.O.’s worth of haymakers into a modest eight by six-inch frame.

An egg tempera nod to Marshall’s Renaissance forebears, the image depicts an all-black figure in a pork-pie hat against a slightly lighter background; fittingly, the painting’s darkness is made visible thanks to the figure’s gap-toothed smile and the whites of his eyes. Pow, pow, and pow!

Kerry James Marshall, A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self (1980). Courtesy of the Met.

Several other paintings at the Met push the envelope on what at first glance resemble modern-day repeats of Kazimir Malevich’s 1915 Black Square. Among these are Invisible Man (1980), Silence Is Golden (1986) and Black Painting (2003-06), this last being a genuine tour de force. A jet-black bedroom interior, the picture features—among other hard to see details—a patterned wall, a bedside table, a Black Panther flag and copy of Angela Davis’ jailhouse book If They Come In the Morning: Voices of Resistance. A conflation of literal and symbolic aspects of blackness, the canvas combines radical aesthetics, revolutionary politics and Dave Chapelle’s lights-out humor.

Other, larger canvases made in the mold of odalisques, portraits, party scenes and monumental history paintings represent, survey, query, and ennoble the story of black life in the late 20th and early 21st century. But few do what the artist does with Untitled (Studio) from 2014. A picture of a painter painting chock-full of allusions to storied antecedents—these include Gustave Courbet’s The Artist’s Studio and Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas—Marshall’s brilliantly illusionistic canvas displays a unique control of art’s oldest medium. At the Met Breuer, Marshall’s is a display of sheer painterly and intellectual mastry.