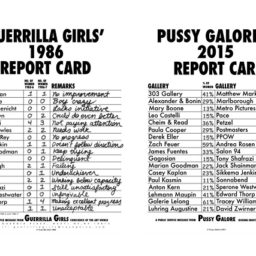

While women in the art world have made strides achieving parity with men, two recent surveys suggest they have a ways to go in the art market and in the museum executive suite.

Women run just a quarter of US art museums with budgets over $15 million, according to the study “The Gender Gap in Art Museum Directorships,” released in March by the Association of Art Museum Directors and the National Center for Arts Research. Those leaders make just 71 cents for every $1 earned by men, the study says. As for artists represented by galleries in New York and Los Angeles, just 30 percent are women, according to the collective Gallery Tally.

“We have a bias in not respecting and not being interested in a feminine way of seeing the world,’’ said Micol Hebron, an L.A.–based artist, performer, curator and teacher who founded Gallery Tally a year ago. “You are more likely to make money selling or reselling art by a man than a woman. And it’s not because women make work that’s less good. It’s because we’ve made capitalism a patriarchal system.’’ Hebron said in a telephone interview that she was propelled to act by the preponderance of male artists in gallery ads in Artforum and in galleries themselves.

Likewise, in a recent post, New York magazine critic Jerry Saltz did his own tally of Artforum ads in the September issue: Of 73 ads for New York galleries, 11 were for solo shows by women—15 percent of the total. Via Facebook, hundreds of artists and activists have joined Gallery Tally: they calculate the proportion of artists represented by specific galleries who are women and create posters communicating the stats. “I think it’s important that the public sees that there are hundreds of people chiming in,” Hebron said. “If collectors went to galleries and said “How come you don’t have more women and artists of color to choose from?’ galleries may change their rosters.”

Cultural Bias

Activists such as the Guerrilla Girls have been protesting the problem for decades. Hebron describes it as “cultural bias” rather than dealers consciously discriminating against women. Bridget Moore recalls a female collector visiting her Chelsea gallery, DC Moore, this spring. The collector said she liked the paintings on display by the realist painter Janet Fish but that they didn’t fit into her collection. Moore asked how much art by women the collector owned. “I saw a little flash go off,” Moore recalled. The collector, whom Moore wouldn’t name but described as sophisticated, said she’d sold her only two works by women years earlier. “We had a discussion about the importance but perhaps lack of recognition of many women artists,” Moore said. The collector ended up buying a Fish painting.

Moore said she believes the art world has generally gone backwards in promoting women artists. “You don’t want to be a bean counter, but all of a sudden it’s swinging in the other direction,” she said in an interview. “I think it’s really worth examining.” (See: “We Asked 20 Women “Is the Art World Biased?” Here’s What They Said.“)

James Abruzzo, a compensation consultant and recruiter who aided in the museum “gender gap” study, predicts that women will land more topflight directorships as veteran male directors retire. “The entire population of leaders is getting older,” he said. While acknowledging that the “old boy network” has played a role in men getting top jobs, he said that it’s lessening. Running a big museum has become more complex and challenging, he said, in part because of rising costs and the difficulty of making exhibits relevant to broad audiences. “Boards are going to choose the best qualified person for the job and they will look way beyond gender,” he said.

What about the pay gap for museum directors? “Men are paid more than women because men ask for more,” Abruzzo said. “I would hope that changes because they’re worth just as much.”

“I’m an optimist about where this is going.”

Sarah James, a recruiter with Phillips Oppenheim who also consulted on the study, said women candidates for top museum jobs tend to explain why they’re competent, while men simply share their vision. Boards (which tend to have more men than women) respond to the men’s strategy. “People are more excited about ideas than qualifications,” said James, who worked with the Metropolitan Museum of Art to elevate Thomas Campbell to succeed Philippe de Montebello as director. James added that female cultural executives in their thirties sell themselves as persuasively as men. “They’re talking the same way. I’m an optimist about where this is going.”

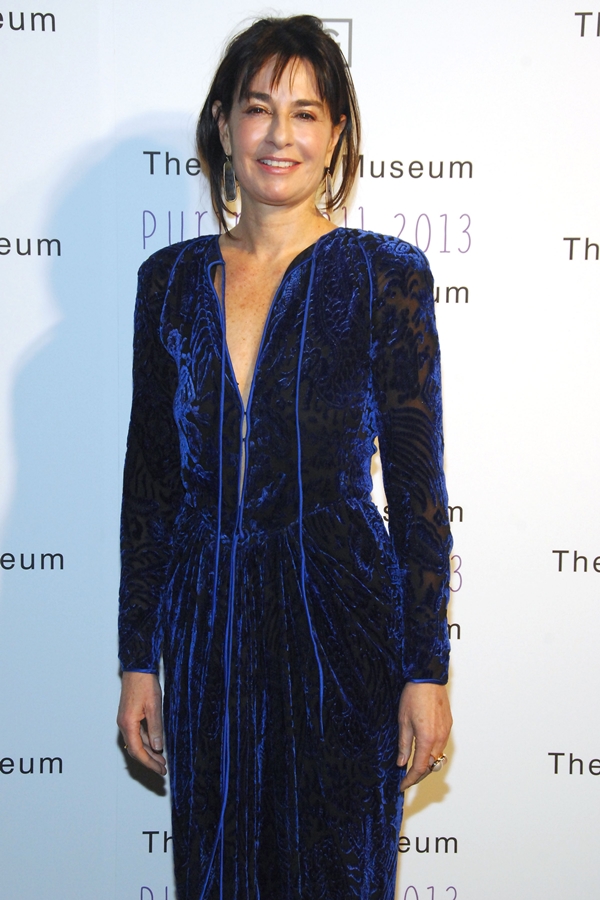

The nation’s most prominent female museum directors include Madeleine Grynsztejn at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago; Jill Medvedow of the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston; Kim Sajet at the National Portrait Gallery; Melissa Chiu, who takes over the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden on September 29; Ann Philbin at Los Angeles’s Hammer Museum; Lisa Phillips at New York’s New Museum of Contemporary Art; Dorothy Kosinski at Washington’s Phillips Collection; Thelma Golden of the Studio Museum in Harlem; and Anne Poulet, who retired from the Frick Collection in 2011.

To close the gender gap, the art world still has work to do. But corporate America is even further behind. There are just 24 female chief executives running companies in the Fortune 500, according to Catalyst, a nonprofit that aims to expand opportunities for women and business. That’s less than 5 percent.