Art & Exhibitions

Art World Report Card: Seven Surprising Ways the Internet Has Screwed the Art World

How cyberspace ruins art, whither Max Anderson, and the other Dallas Buyers Club.

How cyberspace ruins art, whither Max Anderson, and the other Dallas Buyers Club.

Alexandra Peers

Image: Library @ Kendriya Vindyalaya Pattom

2008

The Seven Surprising Ways the Internet Has Screwed the Art World

We all know the Internet has accelerated the art world, flattening prices, boosting the growth of fairs, fueling the practice of snapping up art sight unseen. But the Internet has changed how things work far more than that: Artists, collectors, and museums are behaving differently in cyberspace and because of it. Here’s how:

1. The truly rare object is now wickedly expensive.

The easy availability of price information on the Internet has standardized prices for many works; one gallery can’t charge all that much more than another for somewhat similar works.

But for truly rare art or objects, especially limited-edition multiples like rare books, the sky is now the limit. You used to suspect that, say, a British first edition of Bram Stoker’s 1897 Dracula with its original sun-yellow, blood-red cloth cover would be pricey, but you didn’t know there were only a handful available for sale worldwide and where to get one. Now you do. (And, based on one 2013 sale, it would cost you about $12,000.) Consider the Mexican painter Jose Salazar: His works are rare, so much so that one might come up at auction only every couple of years. When the last one did, at Neal’s in New Orleans, collectors found it and it went for triple its estimate, or $564,000.

2. It’s fueled the art boom by inspiring false confidence.

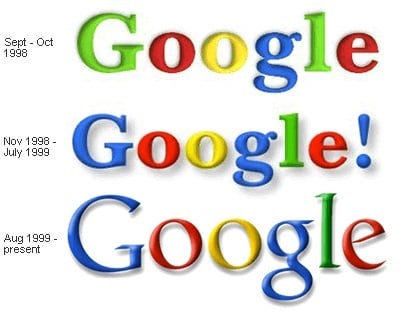

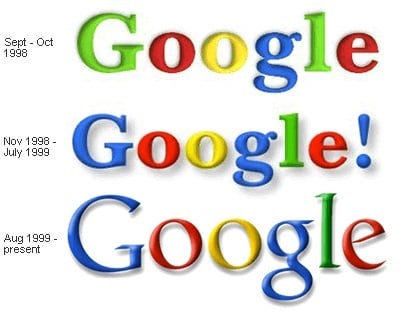

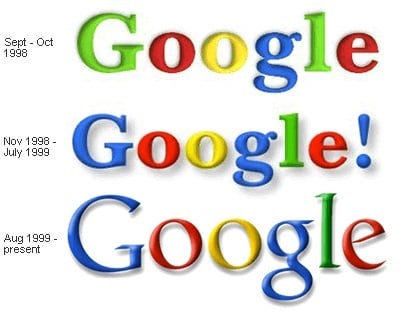

“Google search an artist’s name and you are an instant expert,” notes Portuguese art collector Antonio DeCordoso, who shops annually at the Armory Show and Art Dubai fairs. It doesn’t quite work that way, of course, he adds, but the Internet provides a burst of comfort and confidence that has meant people buy more quickly, if not much less foolishly.

3. The Internet has created new power players and ways to be ones.

There’s a pecking order in the museum world that has existed for decades, but it’s being upended. The century-old Frick Museum, plus the Getty and the Dallas Museum of Art, have fewer Twitter followers together than the Andy Warhol Museum, a social media behemoth at 629,000 followers. (Museum director Eric Shiner says the Warhol has made social media a priority.) Similarly, the number of visitors to Paddy Johnson’s Art F City blog outpaces the circulation of some art magazines. It’s comparing apples to oranges, of course, and isn’t necessarily negative for the art world—unless you are one of the laggards.

4. It’s fueled the production of multiples and “near” multiples.

Some art-world watchers—the Baer Faxt’s Josh Baer among them—argue that it’s actually changed the art that artists are making; that they are creating bodies of work with little dissimilarity precisely so they can be traded easily, and sight unseen.

5. Everyone is now an art-market quarterback.

The Internet started a cottage industry of analysis of, and investment in, the art market, just as the manageability of sports statistics fueled the explosive growth of fantasy leagues. An industry of experts with no institutional memory? Lucky us.

6. It’s crystallized groupthink.

The art world was always a gossipy place, but you used to have a day or two before a consensus on, say, the Whitney Biennial was reached. No longer. Even the casual online skimmer can immediately feel they’ve read so much that they’ve already seen the show—or at least floor three.

7. Who are all these people—and were all of them invited?

Remember paper invites? At first it was great when Blackberries took off and all you had to show at a check-in was your e-vite. Now, websites for events serve as to-do lists for party crashers, who always seem to know somebody at a museum, and can either talk their way in or bottleneck the desk while they name everybody in their class at Cooper Union. The good news is so many people are trying to get into art parties that it’s making the art world more fun and magnetic. The bad news is the crashers are in line ahead of you.

Max on the Move?

“Manhattan is becoming a mall for hedge-fund managers, tourists, and Russians,” said Maxwell L. Anderson, director of the Dallas Art Museum, at an April 12 panel on the growth of cultural districts. Sour grapes, gracious hosting (a Brooklynite was on the panel), or angling for a Brooklyn Museum job in 2018? That institution’s current director Arnold Lehman, one of the longest-serving art museum directors in the US, has said he will step down around then.

Anderson’s last two museum stints—at the Indianapolis Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art—were both five years. He came on board in Dallas in 2012.

But a move back to New York City, his hometown, is “not for me,” Anderson said after the panel, who headed the Whitney from 1998 to 2003, until problems with its notoriously difficult board sent him packing. (Ironically, they parted company over his desire to expand the museum, a project that was later green-lighted in another form.)

Sorry to hear you are not coming home, Max, we—at least those of us not on the Whitney board—would welcome you back.

And as for the cultural districts panel, among its conclusions was that more than 100 million Chinese, Indian and, yes, Russian, middle-class tourists will be headed to US art institutions in coming years, and it is the museum community’s job to prepare for them.

The LGBT Factor

These days, the “Dallas Buyer’s Club” refers not to the AIDS-related movie starring Matthew McConaughey, but the real estate boom the LGBT community is bringing to the Texan town. Much has been written about the success of the Dallas Art Fair, including by myself, but one missing piece of the puzzle—or ingredient of a successful formula—is how inclusive and aware the city has been of “alternative” lifestyles, traditionally a cornerstone of any arts community.