Art & Exhibitions

Ben Davis On Why Kazuo Shiraga Was One of the World’s Most Radical Painters and Still Is

The Japanese painter Kazuo Shiraga is a 50-year "overnight" success.

The Japanese painter Kazuo Shiraga is a 50-year "overnight" success.

Ben Davis

These days, Japan’s Gutai movement is considered one of the most path-breaking, explosively original things to have happened in art post–World War II.

It was not, however, well treated when it first arrived in New York.

When Gutai appeared at Martha Jackson gallery in 1958, the New York Times’s Dore Ashton, a champion of the New York School, dismissed its stars as imitators, “completely orthodox in their devotion to what they believe Jackson Pollock represented”—a scolding that it has taken art history a half-century to get over.

Kazuo Shiraga (1924–2008) has steadily gained historical momentum as Gutai’s biggest name. He’s celebrated right now in a big exhibition at the Dallas Art Museum alongside fellow Gutai great Sadamasa Motonaga, and has dueling shows of his feverishly handsome canvases at Mnuchin and Dominique Lévy galleries in New York; in the latter case, juxtaposed with some nice ceramic sculptures by Satoru Hoshino. Upcoming, too, on April 30, at Fergus McCaffrey Gallery in New York, is a joint show of the work Kazuo and Fujiko Shiraga. There is a lot of interest in the artist, clearly.

I haven’t seen the Dallas show, but I have a question based on the two gallery shows I’ve seen: Is New York still getting Gutai wrong?

What do you see between Lévy and Mnuchin? Ample evidence of Shiraga’s genius, with some three dozen of his vortex-like compositions spread between the two spaces, hinting equally at his acrobatic body and free mind. Amid the soul-searching of Japan’s post-war wreckage, the Gutai group was mainly united by the imperative to junk the past and explore uncompromising newness.

Shiraga joined Gutai in the early 1950s after founding his own experimental art group, Zero-kai, with a beatnik hostility to art as commerce. “Why on earth is there a profession called ‘painting?,” he declared in 1955. “All I want to do is paint. Isn’t it better to earn a living by doing something else?” And so he tried painting in a completely unheard of way, first with a palette knife, then a piece of wood, then just with his fingers. At last, when finger-painting wasn’t direct enough, he discovered his feet, creating a rig to suspend himself above his canvases, slashing his toes through masses of oil paint to carve out the splattery arabesques for which he is known today.

![Kazuo Shiraga's <em>Enji [Dark Red]</em> 1983<em>Chikusei Shohao [Little King incarnated from Earthly Empty Star]</em> 1961](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2015/02/Shiraga-install-Mnuchen.jpg)

Left to right: Kazuo Shiraga’s Enji [Dark Red] (1983) and Chikusei Shohao [Little King incarnated from Earthly Empty Star] (1961)

Photo: Courtesy Mnuchin Gallery

What might you miss at Lévy and Mnuchin? For one thing, there is little sense of the development in between Shiraga’s early-60s and later work (Lévy told ArtNews that she couldn’t decide whether to hang the show chronologically or thematically). In fact, after 1963 Shiraga embarked on a new series using skis. He didn’t show on his own at all between 1964 and 1973, and even took a year off to become a monk of the Tendai school of esoteric Buddhism. The return to classic-type foot painting was sparked by the suggestion of the president of Tokyo Gallery, who thought that the experiments he had been doing in the meantime were not deserving of a solo show.

If you pause to look at the paintings, there are differences to be remarked upon. Shiraga’s early works have an undertone of distress which is sometimes read as reflecting the then-recent trauma of the war. In artworks (not seen here) that culminated his early foot-painting period, he used the pelts of dead boars instead of canvas, the clotted paint in fur evoking burst roadkill. In a proto-Hirstean move, he also made sculptures consisting of cow livers preserved in formaldehyde.

Kazuo Shiraga, Inoshishi-gari 1 (Wild Boar Hunting 1) (1963), from the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo

Fur, paste, and oil on panel

Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo

Some of Shiraga’s late works maintain the sense of violence, like the 1985 Suiju at Lévy. But they can also be drastically lighter, something the artist said his friends remarked upon. Consider the diaphanous baby blue of Furuyuki (1999) at Lévy, or the choppy, glowing yellow Chimosei Hakujitsuso [Daylight Rat incarnated from Earthly Wasted Star] (2001) at Mnuchin. There’s nothing like them in the early period.

![Kazuo Shiraga, <em>Chimosei Hakujitsuso [Daylight Rat incarnated from Earthly Wasted Star]</em>(2001)](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2015/02/Chimosei_Hakujitsuso_2001sm0.jpg)

Kazuo Shiraga, Chimosei Hakujitsuso [Daylight Rat incarnated from Earthly Wasted Star] (2001)

Photo: Courtesy Mnuchin Gallery

There’s something else worth stressing that might get lost here. Let’s be honest: Shiraga has become the most sought-after of the Gutai artists precisely for the reason that Dore Ashton dismissed his work in 1958. That is, as opposed to some of the more experimental Gutai multi-media works—say, Atsuko Tanaka’s Light Dress (1957), a garment designed to outline the body with hundreds of blinking lights—Shiraga’s output in particular looks comfortingly like a classic type of blue-chip abstraction. For his part, Shiraga recollected seeing American-type painting before embarking on his experiments and considering it “very fresh,” though he claimed to have been more attracted to the raw aesthetic of Jean Dubuffet.

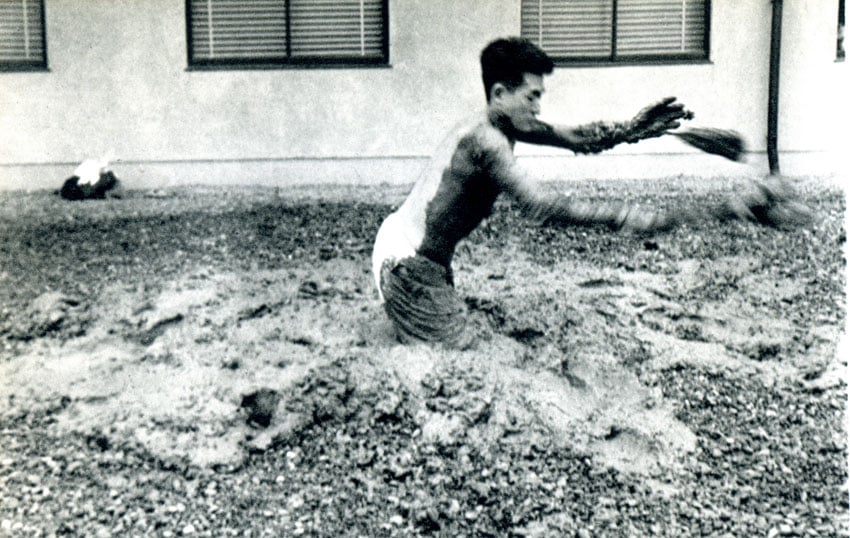

Photo documenting Kazuo Shiraga performing Challenging Mud at the 1st Gutai Open Air Exhibition, Tokyo.

Gutai artists were way ahead of their time in thoroughly embracing the live aspect of art, and Shiraga’s foot-painting ritual was not just a means to an end, but a major aspect of the art all by itself. As an indication of just how far he could tilt things towards the performantive, in 1955 he staged one of Gutai’s most oft-cited events, Challenging Mud, for which he stripped almost naked and tried to wrestle a pile of uncooperative clay into shape.

Remarkably, there seems to have been more accent on the event-based nature of the work back in 1958 at the Martha Jackson show, where each artist was represented by two works, accompanied by film and photos documenting their process of creation. In 2015, the emphasis has definitely moved to the art as wall candy, though Lévy does offer a cool film clip of Shiraga performing, giving a sense of the missing presence:

And yet, there’s a final note worth considering when it comes to Kazuo Shiraga’s presentation in the gallery—because the artist himself was wise to all of these questions, anticipating this whole discussion. If few of his pre-1957 paintings exist today, this is because they were executed on Japanese paper, and consequently were ephemeral by nature. The shift to canvas came in 1958, at the coaching of the French art critic Michel Tapié (1909–1987), who wanted to promote Gutai on the international stage. Tapié thought canvas fetched higher prices, travelled better, and would resonate with Western audiences.

“[W]e were rather exhausted after an intense period of experiments,” Shiraga recalled. “In 1955, 1956, and 1957, we were cranking up new things. At the moment we grew rather tired, he [Tapié] came along and said painting was better.”

Indeed, it was Tapié who spearheaded that poorly received New York gallery show, advertising it as the next logical development of international abstract painting. In a New York that was then puffed up on its own glory as a capital of the painted canvas, the Frenchman’s rhetoric raised hackles. It caused critics to dismiss Gutai as derivative. In the long run, however, it is precisely the fact that Shiraga’s art fits so well as a variation on abstract painting that has made it so very successful, and the current Shiraga renaissance shows that Tapié may have given one of art history’s great pieces of New York career advice.

“Body and Matter: The Art of Kazuo Shiraga and Satoru Hoshino” is on view at Dominique Lévy Gallery, 909 Madison Avenue, through April 4, 2015. “Kazuo Shiraga” is on view at Mnuchin Gallery, 45 East 78th Street, through April 11, 2015.