Art & Exhibitions

Berlin Gallery Beat: Five Must-See Shows in May

We review the exhibitions you simply cannot miss.

We review the exhibitions you simply cannot miss.

Alexander Forbes

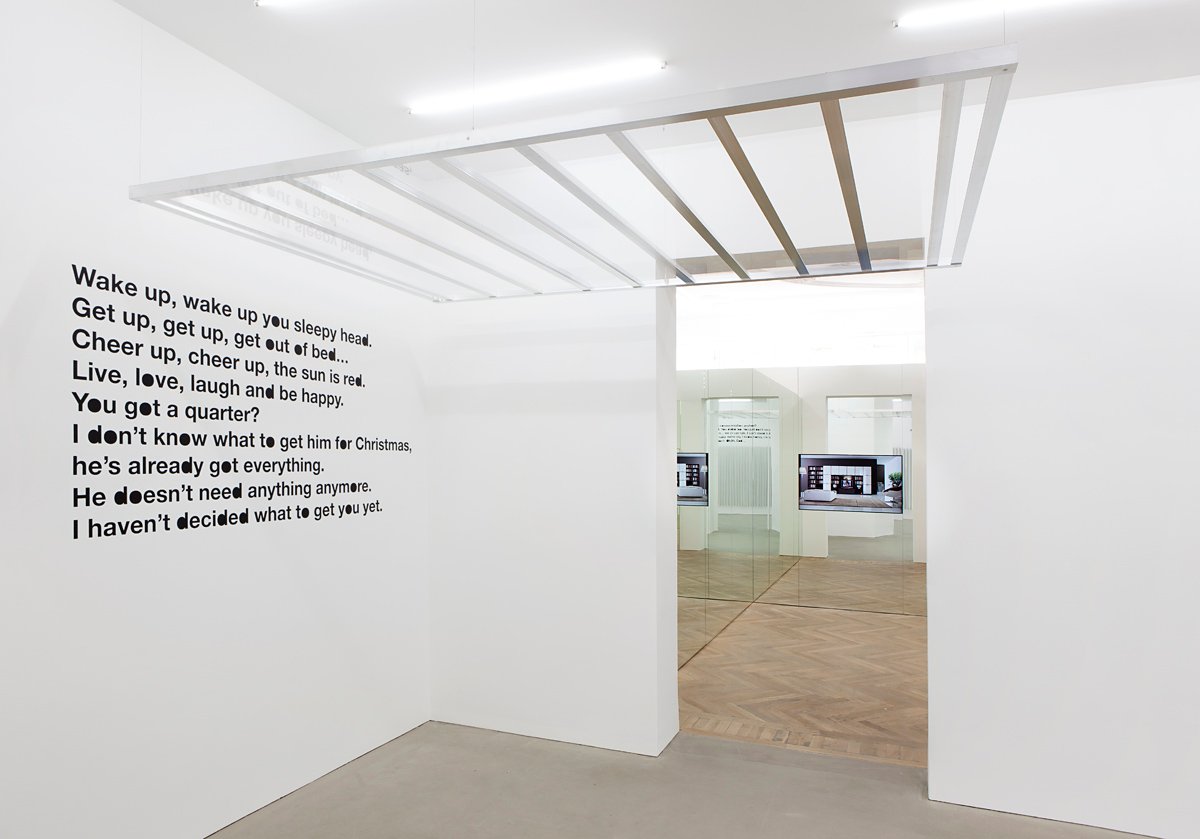

Installation view: Gerold Miller Monoform

Courtesy Mehdi Chouakri, Berlin

Reproduction Jan Windszus, Berlin

Mehdi Chouakri, Gerold Miller, Monoform, closes June 21

Miller’s work is often something of a misfit in Berlin. His lacquered aluminum paintings are so precise in their square applications of oft-neon colors and their sometimes circular cutouts. They’re so, well, shiny. It’s made to measure Chelsea fodder—he’s a constant hit at art fairs too—but in Berlin, with the city’s penchant for nostalgic-looking art in a shade of brown, it can be jarring. His latest at Mehdi Chouakri astounds for a different reason.

Miller has reduced his pseudo-painterly practice to its most essential form: the right angle. It’s seen here in a series of works titled Monoform in which he has simply bolted pairs of painted, skinny pieces of aluminum folded to 90 degrees along their center directly onto the wall at about picture height. From a sculptural standpoint, the works throw down Judd with a clang. Art historically, they engage in the long-running minimalist project of creating contentless picture planes. But it’s the Monoform works’ phenomenological stance—particularly in conversation with his previous paintings—that proves most interesting. Used to being able to find ones reflection in a Miller (a very pre-recession phenomenon, I might add), the viewer searches the gallery wall only to find a void left between the familiar structures.

Installation View, David Claerbout, Johnen

Photo: Jens Ziehe, courtesy David Claerbout and Johnen Galerie, Berlin.

Johnen Galerie, David Claerbout, closes June 21?

Claerbout’s latest show might as well be an application for his native Belgium’s pavilion at the Venice Biennale. He shows just three works: two moving photographs and a video, with screenings every twelve minutes (more galleries need to be doing this with time-based art). To the right upon entering the gallery is Oil Workers (2013), a restaging of a photograph Claerbout found online of Shell employees in Nigeria waiting out a downpour under a bridge on their motor scooters. The photo and its counterpart, Highway Wreck—a black and white series shown in a 35 minute-loop in which modern firefighters attend to a car crash Claerbout recreated from a 70 year old photo while other modern motorists look on—were made with 45 cameras placed at equidistant intervals around their subjects, allowing for a subtle movement through the images. It’s a trick we’re seeing increasingly employed in advertising and digital publishing—especially with the rise in the tablet as a leading platform for content consumption. In an art context, however, the technique creates an interesting commentary on the documentary. It displaces a temporal specificity within the photographs, allowing them to speak as conditions rather than moments, thus increasing their affective potential. Travel (1996–2013) is the show’s standout. Inspired by and set to a piece by French composer, Eric Breton, the work brings its viewer on a journey through an entirely imagined forest. Claerbout envisioned the work in 1996 but only found technology powerful enough to achieve its entirely realistic scenes last year. (You wouldn’t know it was a digital fake if he didn’t’ tell you.) The experience is transcendental, one escapes aided by the oversized bean bags on which he is invited to lay, lets go of pretense, and becomes absorbed in the work. Claerbout demonstrates an impressionist’s sensitivity to light, exalting the natural world digitally the way Caspar David Friedrich did in oil. In a contemporary context, Travel is utterly radical, rejecting the tenets of postmodern art in exchange for a more precarious but also more hopeful metamodern mind-set.

Installation View, Liam Gillick, Revenons à Nos Moutons, Esther Schipper

Photo: Andrea Rossetti, courtesy Esther Schipper, Berlin.

Esther Schipper, Liam Gillick, Revenons à Nos Moutons, closes June 28.

The sculptures in Gillick’s eighth solo exhibition with the gallery represent a stark reduction over previous works. Gone are the bright and shiny pantone wheel of colors, which coat the artist’s aluminum, architectonic structures and tint the sheets of Plexiglas that fill their gaps. We get only bare aluminum and clear panes this time around. They’re less fun than their bright counterparts—not that any were supposed to be—and more strictly purpose-oriented and banal. In their continued shade-like reference to the basic forms that structure the workplace—cubicles, bookshelves, false ceilings, and more—they lack the feel-good artifice with which one might justify the box in which they sit. The sculptures each come with a quote pulled from Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974) which centers on an episode of surveillance botched by a logical-ethical conundrum, leading to conclusions exactly 180 degrees from the truth. The mash-up subtly suggests that if we can misinterpret clear words on a magnetic tape, we might do well to reevaluate how “known” all other entities might truly be.

Presented in a small mirrored room towards the back of the gallery, Hamilton: A Film by Liam Gillick comes unintentionally at the same issue from the opposite tack. Created for Richard Hamilton’s major retrospective this past winter at Tate and the ICA in London, the film trains a keen eye on artifice, presentation, and the practice of art itself. It starts with Hamilton’s The Critic Laughs playing on a TV set in a hyper-designed modern living room, gives a brief history of the invention of Plexiglas, cuts to Hamilton catalogues on a Bauhaus-era coffee table, and winds up with a side-split Duchamp being interviewed about his theory of art by Hamilton in 1959, a recording of Que Sera Sera playing in the background as if to give a great shrug at intentionality, artistic or otherwise.

Installation View, Simon Dybboe Møller, Aperture and Orifice, Galerie Kamm

Photo: Courtesy Galerie Kamm.

Galerie Kamm, Simon Dybbroe Møller, Aperture and Orifice, closes June 14.

Møller probably doesn’t get a lot of likes on his Instagram account. Taking up the Japanese tradition of Sampuru or wax-molded, resin cast fake food, Møller has lined the gallery’s walls and tables with mostly eaten plates of mackerel and rye bread, salad nicoise, moules frites, and a particularly revoltingly scatological trio of lamb shanks. The works mark a brilliantly simple take-down of our hyper-documenting, me-centric culture where every meal, every morsel of energy-producing comestible, is treated like, well, a work of art. Taking Møller’s path down the post-bite track, one sees the potentially vile trend that could become the normcore of food porn: #regular.

Rather than placing blame on the capitalistic individual obsession, however, Møller looks towards the camera itself in the exhibition’s accompanying video Untitled (How does it feel) (2014). It’s an oblique homage to the rather nude video flash-in-the-pan R&B star D’Angelo’s produced for his 2000 hit. Here, though, the only body with which Møller lusts after is the slick black frame of the Canon 5D Mark II. The camera stands as one of art-thought’s most underappreciated revolutions, technologically nullifying the separation between still and moving image like no apparatus before it, and, several years down the line, leaving us with a constant picture-face in case someone’s shutter is on silent.

Installation View, Sovak, Themes and Variations, Moeller Fine Art

Photo: Courtesy Moeller Fine Art

Sovak, Themes and Variations, Moeller Fine Art, closes June 28.

It’s been 15 years since Pravoslav Sovak has enjoyed a major exhibition. Now 87, the Bohemian artist, based in Switzerland since 1968, has hung a much-overdue reprisal of that 1999 retrospective from Vienna’s Albertina in Berlin. The exhibition’s works span from 1968-2013 and continues a current trend of resurrecting lost artistic gems—current Berlin showings of Geta Brătescu and Georg Karl Pfahler also come to mind.

It focuses on three main series of works on paper. His series Beauties and Desert Sheets exemplify the artist’s breadth. The former, more recent works play on pop with their assemblages of transfer and printing techniques, layering palm tree-clad landscapes, shots of gallery-goers, and suburban sprawl. The later, which combine highly detailed etchings and drawings of scenes from the American West on a grid-like background, recall early works on paper by Lyonel Feininger. The show additionally features a new set of wryly humorous collages in which Sovak often places minute images of himself, proof positive that despite his age, he’s no curmudgeon.