Art & Exhibitions

“Degenerate Art” Show at the Neue Galerie Exposes Paradox of Nazi Prejudice

Nolde, Belling, and Barlach were praised by the Nazis and labeled "degenerates."

Nolde, Belling, and Barlach were praised by the Nazis and labeled "degenerates."

Rozalia Jovanovic

Emil Nolde, Still-Life with Carved Wooden Figure (1911).

Courtesy Museum Folkwang, Essen. © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll.

“Degenerate Art: The Attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany, 1937,” a fantastic exhibition that opened this month at the Neue Galerie, is not the first exhibition aimed at recreating in part the notorious 1937 “Entartete Kunst” (“Degenerate Art”) exhibition organized by the National Socialists party in Munich as part of its battle against perceived cultural decay. There was, for instance, LACMA’s 1991 show “Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany.” But what sets this show apart is its presentation not only of the works that exemplified cultural “degeneracy” (among them Cubist, Dadaist, and Surrealist works), but also of the paintings and sculptures that were considered exemplars of German art. These were shown concurrently in the “Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung” (“Great German Art Exhibition,” or GDK) at the Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German Art), another major Munich exhibition whose goal was to lay the foundation for a new German art, and to provide appropriate models for artists to follow. The GDK opened on July 18, 1937, just one day before the opening of the “Degenerate Art” show.

In the first room of the Neue Galerie show, which was organized by art history professor and museum board member Olaf Peters, works that exemplified both the “degenerate” and state-sanctioned types of art are shown together, and, for the most part, it seems clear which art falls into which category. The kitschy triptych of classical nudes The Four Elements (1937), painted by Adolf Ziegler—the president of the Prussian Academy of Fine Arts who was tasked by Hitler with purging German museums of “degenerate art”—was an example of the kind of saccharine portraits and landscapes favored by Hitler. It was the centerpiece of the GDK show, after which it hung over the Nazi leader’s mantel. Meanwhile the dark triptych nearby, Max Beckmann’s modernist masterwork Departure (1932–35), features ambiguous narratives of torture, sin, and salvation, and seems to belong squarely to the “degenerate” camp.

Some of these you’re likely familiar with. But in the context of this exhibition, which channels some of the freak show aura of the original display, they take on defiant and goulish grandeur.

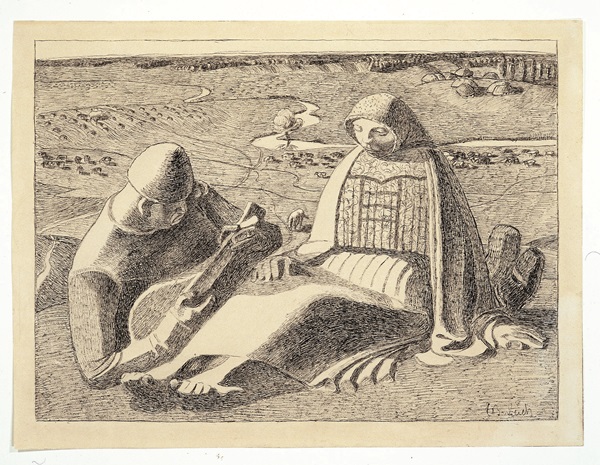

Ernst Barlach, Russian Lovers (1907).

Courtesy Ernst Barlach Haus − Stiftung Hermann F. Reemtsma, Hamburg.

It’s not always so clear, however, which art works were deemed degenerate and which were praised, which art the Nazis were for or against, partly because they themselves didn’t know. The jury assembled to select the work for the GDK show had difficulty determining what kind of art would represent the official German art, and even considered Expressionism for a hot minute before grouping it amongst the “art of decay.” The “degenerate art” show, on the other hand, was slapped together by Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s minister of propaganda, to serve as a “distorted counterimage” of the accepted art, as Peters puts it in his catalogue essay. A few artists in the “Entartete Kunst” show, namely Emil Nolde, Rudolf Belling, and Ernst Barlach, exemplified this confusion of politics.

Goebbels was an early admirer of the work of German-Danish Nolde. One of the first Expressionists, Nolde did a brief stint with the revolutionary Die Brücke (“The Bridge”) group and was a member of the Berlin Secessionists, an organization that aimed to provide an alternative to the state-run Association of Berlin Artists. But that and the artist’s membership in the Nazi party didn’t prevent him from being a prime target of the campaign against the art of decay when his aesthetics fell out of favor with the National Socialists. Over 1,000 of Nolde’s works were confiscated from German museums in 1937, more than that of any other artist, and 50 paintings, prints, and watercolors were included in the “Degenerate Art” show. His cycle of prints The Life of Christ was the centerpiece. Nolde’s works are likewise well-represented in the Neue Galerie show, with three paintings and 12 works on paper.

Emil Nolde, Sea with Evening Sky, undated (circa 1938-45).

Courtesy Stiftung Seebüll Ada und Emil Nolde, © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll.

Complicating Nolde’s legacy is his membership in the National Socialist party and his fervent support of the new regime even after his work was deemed degenerate. He ingratiated himself with Goebbels and the party in an effort to get back in their good graces and to the same end made an attempt to distance himself from the modernists. His efforts were successful for a time, and Goebbels ordered the return of work that Nolde loaned to museums including his The Life of Christ cycle, but his work continued to embody the aesthetic abhorred by Hitler. Nolde was ultimately forbidden from selling or exhibiting. His affecting paintings now stand as emblems of the failure of modernism to represent democratic ideals.

Commanding the center of the first room in the Neue Galerie show is a series of bronze sculptures by the Expressionist sculptor Ernst Barlach, another figure around whom, as with Nolde, questions about the essence of German art swirled. Barlach was initially a favorite of Goebbels, who wrote enthusiastically in his diary about Barlach’s wood sculpture The Berserker, a bronze version of which is on view at the Neue Galerie. Though Barlach was included in the “Degenerate Art” show, it was “with only one example,” according to Peters. “This might indicate that Goebbels was still admiring him, and if you look at the depot-images more works by him (at least the famous Magdeburger Ehrenmal) were confiscated,” Peters told artnet News over email, referring to Barlach’s anti-war sculpture. The Magdeburger Ehrenmal caused a controversy when it was installed in Magdeburg Cathedral in 1929 because it depicted soldiers in pain and terror rather than as heroic figures.

Ernst Barlach, The Berserker (1910).

Courtesy Ernst Barlach Haus Stiftung Hermann F. Reemtsma.

Rudolf Belling provides an interesting example of an artist who was in both the “Degenerate Art” show and the first GDK exhibition—“a typical Nazi mistake” as Peters puts it. Though Belling’s work was being confiscated and destroyed, and he moved for a time to Istanbul, two works of his were submitted to the GDK exhibition. One of them, Der Boxer Schmeling (The Boxer Schmeling) (1929), was included. Meanhwhile, several sculptures of Belling’s were included in the “Degenerate Art” show. When organizers of the GDK exhibition noticed the inconsistency, they allowed his sculpture of the boxer to stay on the grounds that it represented the physical Aryan ideal, and summarily removed his work from the “Entartete Kunst” show.

“That shows how he tried to survive during that era since he must have applied to be included [to the GDK show],” said Peters. “It also indicated that the jury and Hitler himself were not aware what works he had produced during the Weimar Republic.”

Within a regime known for its bureaucratic efficacy in the service of diabolical ends, this confusion comes as something of a relief. Despite the attempts of Hitler, Goebbels, Ziegler and their ilk to catalogue the art and artists of their time using the same reductive and rigid systems that they applied to their other endeavors, their own official exhibitions managed to undermine their rhetoric. There’s something of this small vindication evident in the paintings and sculptures currently on view in the Neue Galerie’s wonderful show.