Art & Exhibitions

Former Frick Director Speaks Out Against Expansion Plan

The Frick's "unique sense of intimacy" would be lost.

The Frick's "unique sense of intimacy" would be lost.

Sarah Cascone

The latest voice to come out in opposition to the proposed expansion at New York’s Frick Collection is Everett Fahy, the director of the beloved institution from 1973 to 1986.

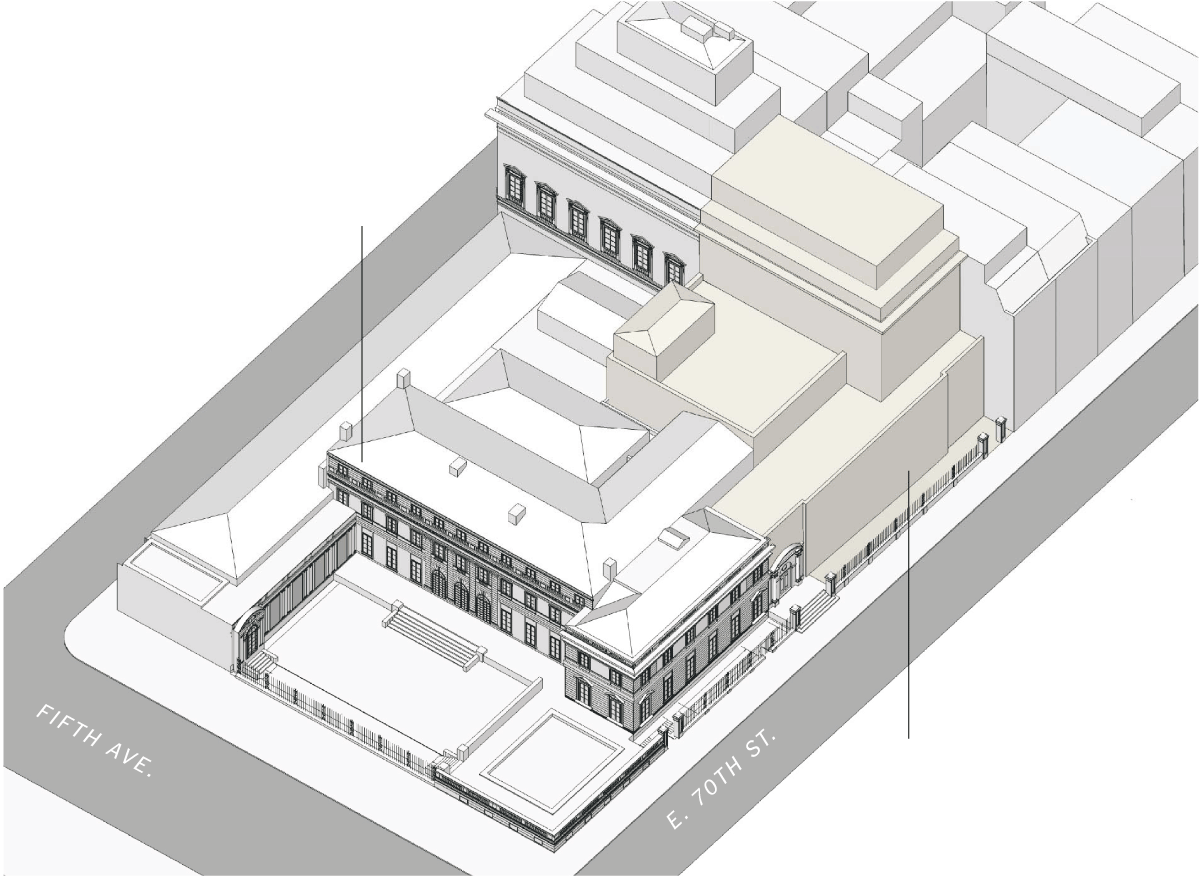

The ambitious plan, announced in June, calls for new a six-story mansion to be built in between the current museum and the nearby Frick library and would destroy an intimate viewing garden designed by British landscape architect Russell Page. The design was immediately met by skepticism by those who doubted the expansion could gracefully mimic the original Beaux-Arts style building, and by outright criticism by fans of the garden.

The museum’s current director Ian Wardropper downplayed the significance of the garden in his official announcement, making no mention of Page even though Nancy Berner and Susan Lowry’s Garden Guide: New York City alleges that the Frick was “one of a number of public projects the English designer undertook at the end of his life, hoping to preserve his reputation for posterity.” Wardropper’s letter claimed that in the 1970s, “to fill the unused lots adjacent to the pavilion, a small garden was created, which has never been accessible to the public.”

“They [the Frick administrators] need to visit Europe,” countered Fahy in an interview with Bloomberg. “You don’t need to walk around. It’s ingenious how he raised the garden so that when you look at it from the street, it seems bigger.”

The Frick. Courtesy Wally Gobetz via Flickr.

Research by Cultural Landscape Foundation founder and president Charles A. Birnbaum, has revealed that when the Frick scaled back previous expansion plans in the 1970s, they commissioned Page to create a permanent viewing garden. The Cultural Landscape Foundation recently added the garden to its annual Landslide, a list of threatened or at-risk land-based art sites.

Wardropper has contested the meaning of “permanent,” arguing to the New York Times that it was permanent only with regard to the “foreseeable minimal needs of the collection,” and that it was intended to “last for at least a few years until the museum could build the building that was needed. We’re now 40 years later and at that point.” If approved, the plan would add 24 percent more space for the permanent collection, and increase temporary exhibition space by half.

An architectural plan for the Frick Collection expansion. Photo: courtesy Davis Brody Bond.

Opposition, however, has been vocal. A Change.org petition from the newly formed group Unite to Save the Frick has attracted 2,000 signatories since being launched in September. The letter argues that the new building would “irreparably damage the unique sense of intimacy that is a hallmark of the Frick experience.”

“It’s a house museum. If it were kept as a house museum it would serve its purpose,” insisted Fahy, echoing the sentiments of many fans of the institution’s current jewel-box feel. “I can’t believe anything close to the current designs would be approved by Landmarks Commission. It’s awful. That intimacy and atmosphere would be lost.”

Interior shot of the Frick Collection, New York. Photo: courtesy the Frick Collection.

As an alternative, Fahey, like Michael Kimmelman of the New York Times, suggests repurposing the Frick library. “If you really need to expand, start here. Young people use the Internet to write their papers. Very few come into the library.”

Wardropper still stands behind the mansion proposal. “People love the place, and they’re afraid that it’s going to change,” he acknowledged. “I have to reassure them this is a modest plan that’s meant to support everything we do.”

Fahey feels differently: “At the very least, the architects have to go back to the drawing table.”