Art & Exhibitions

Glasgow International Festival Clamors for Attention, In a Good Way

Glasgow's biennial art extravaganza draws major talent.

Glasgow's biennial art extravaganza draws major talent.

Coline Milliard

“NOW SING,” reads a sculpture by Michael Stumpf, cheekily perched on the façade of Glasgow School of Art’s brand-spanking-new building. The installation carries on across the road, inside the original Mackintosh-designed institution, but it’s as if the entire city has enthusiastically responded to the request. As Glasgow International Festival launches its sixth edition, art clamors for attention everywhere in town. Among the 50-odd exhibitions featured this year are inflatable sculptures in former Victorian baths courtesy of Anthea Hamilton and Nicholas Byrne, pink flamingos spurting water in an underground car park-turned-swimming pool (staged by the local, and aptly named, Underground Car Park collective), and hours of video to watch.

Glasgow is known as the UK’s second art capital. “It’s an artists’ city,” a local told me when I arrived, referring to the close-knit community that has given Britain an outstanding number of Turner Prize winners in the last few years. GI, as the festival is affectionately called, has long embraced this generosity of spirit. New director Sarah McCrory continues the tradition, launching her first edition with a coup: the reopening of the McLellan Galleries, in the center of town. Campaigners have pushed the idea for years. But the city took quite a lot of persuading, and the venue’s fate after GI remains uncertain. For now, McCrory has filled the downstairs of the eerily derelict Victorian museum—all ornate ceilings and grand marble staircases—with films by art world darling Jordan Wolfson, who recently wooed crowds with his uncanny animatronic dancer at David Zwirner New York.

The display is a fully-fledged solo show. Wolfson’s ambitious Raspberry Poser (2012)—which collages urban views of SoHo, floating animations of a condom full to the brim with hearts, and jumping, almost cute HIV viruses—is presented with some of his earlier, more modest pieces. One of them is the Crisis (2004), in which a young Wolfson rambles on about art and whether or not he should embrace it. “I probably love art more than anything,” he says with a cringeworthy earnestness, which, paradoxically, renders the piece all the more endearing. In Untitled (2011), clamped lobster claws pasted with gay porn are slowly released from their elastic bands. The glacial pace, and sheer oddity of the images, make for compulsive watching.

Hudinilson Jr, McLellan Galleries

Courtesy the Artist and Glasgow International

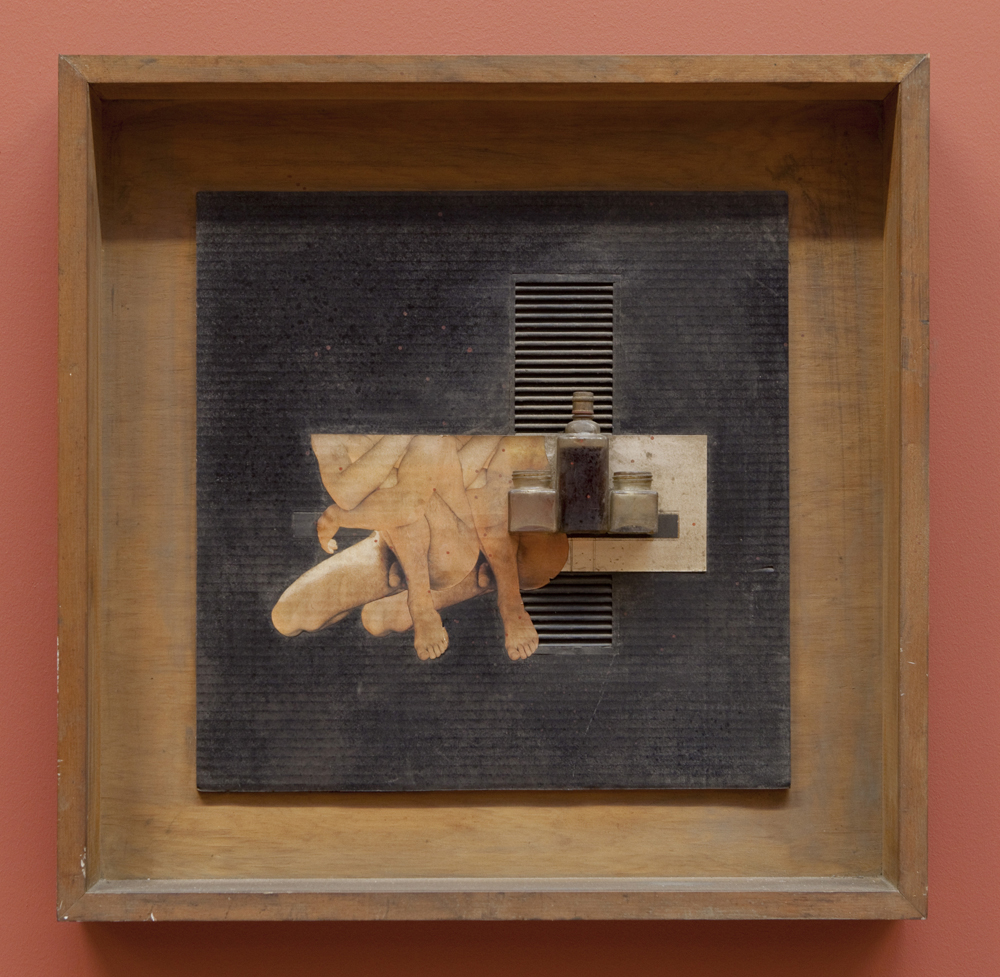

Photographer: Alan McAteer

The muted paintings by Avery Singer—geometrical figures rendered with a combination of Google Sketch Up modeling and black and white stencils—feel underwhelming after such a boisterous opening salvo. But the Wolfson extravaganza strikingly echoes the work of Hudinilson Jr, also on the first floor. The Brazilian artist died in relative obscurity last year, leaving behind a genuine treasure trove of collages, Xerox works, scrapbooks, and sculptures, so poorly documented that the precise date for most of them is still unknown. Presented here among an extensive selection of works—the artist’s largest ever in the UK—the reliefs merging abstract elements made with found material and cutouts of erotic male figures stand out. Dense and tactile, they pack the fervor of reliquaries, and the formal precision of the best neoconcretist sculpture. The Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid and MoMA are rumored to be on the case.

McCrory has purposefully discarded any potential theme—a smart move, considering the often-pompous conceptual umbrellas large-scale visual art events generally adopt. Yet many of the presentations (some directly curated by McCrory, others not) chime with each other. From Wolfson on, the use of mainstream images, be they digital or mass media, is one of these threads. At Glasgow’s leading commercial art gallery, The Modern Institute, Anne Collier presents a stunning selection of photographs dissecting the politics of the gaze. A series of images shows a hand holding the photograph of an eye. A diptych features the found postcard of an African girl playing with a camera, the mechanical object in stark contrast with her tribal beads. Collier includes the back of this “ethnographical souvenir”. The caption reads “Say Cheese Before I Click (Turkana Girl), 1912.” The photographer photographed is one step further removed in Collier’s clinical mise en abyme.

The converted tram shed Tramway is traditionally GI’s mother ship, and this year it puts the American performance and video artist Michael Smith in conversation with the Welsh Bedwyr Williams. The former stages his alter-ego, Mike, in a series of semi-absurdist situations: as the proud owner of a fictional stage lighting company, as a dictionary obsessive, or as a man preparing a party that is never to be. Smith flirts with the credible, without ever allowing for suspension of disbelief. His is the humor of the familiar. When he feels all his pockets for his mobile phone, only to repeat the gesture for his glasses, then sunglasses, he could be anyone’s uncle, but the balance is out of whack—the clumsiness over-amplified.

Bedwyr Williams, Tramway

Courtesy the Artist and Glasgow International

Photographer: Alan McAteer

Williams, who represented Wales at the last Venice Biennale, has gone down the ribald route. His film Ecth imagines a retro-futurist dystopia whose characters—queen, king, courtiers, and jesters—belong to an improbably Rabelaisian acid house club scene. Body-built demons accumulate chewed gum to make a phallic sculpture. And indeed accumulation is the key principle here: in Williams’ new world order, hoarders are the most powerful. Social status is measured by the quantity of stuff one owns, ideally worn all at once. Perhaps it’s not such a new world order after all, just a slightly disturbing reflection of ours.

Glasgow as a subject slips in and out of the program. Lucy Reynolds’ Feminist Chorus at Glasgow School of Art should be singled out. Installed in a corridor known as the Hen Run—high above a glass roof, it used to give male students a good view of the female students’ petticoats as they went to their studio—the sound installation broadcasts today’s female students reading the names of their predecessors dating back to the opening of the school in 1845. The effect is as atmospheric as it is cacophonic, a riot of disappeared voices, reanimated.

The exhibition of the Mexican artist Gabriel Kuri at Common Guild merges his semi-abstract sculptures and donated items. At the end of the show, the latter will be passed on to the GLAD Action Network and the Unity Centre, two local charities working with homeless people and disaster victims. The charities have been very specific about the kind of items they accept: sleeping bags, bed linen, toiletries. Here these everyday objects appear both fully part of the work, continuing the artist’s exploration of contrasting textures and forces, and ready to be taken away. Value and use oscillate between art and non-art, discourse and relief. Installed in the individual sections of a polling table—part of Kuri’s ongoing research on the way people exert their right to vote—they also talk of our political choices, and their very real consequences. Only months ahead of the independence referendum in Scotland, these objects acquire a particularly loaded resonance. In many ways, this piece could sum up GI as a whole: locally grounded but international in scope, open-ended, and very much of its moment.