Art & Exhibitions

In Review: London’s Top 10 Exhibitions, from Herald Street to David Zwirner

Francis Upritchard, Marius Bercea, Miroslaw Balka are among those who elate and disturb us.

Francis Upritchard, Marius Bercea, Miroslaw Balka are among those who elate and disturb us.

Coline Milliard

Djordje Ozbolt, “Mens Sana in Corpore Sano,” March 29–May 11.

Courtesy Herald Street.

Djordje Ozbolt, “Mens Sana in Corpore Sano,” Herald Street, closes May 11.

It isn’t often that an exhibition puts a smile on your face. But Djordje Ozbolt’s paintings and sculptures at Herald Street do just that—and much more. In this new series of works, the Serbian-born, London-based artist tackles modernist myths with humor and a lightness of touch so often missing when dealing with the loaded legacy of Western art history. Here, a Brancusian wooden sculpture (Whatever Tickles Your Fancy, 2014) sports comedy glasses and a mustache. In the painting Papa Don’t Preach (2014), an African statue à la Demoiselles d’Avignon attacks a more ethnographically accurate figurine with a Technicolor replica of Brancusi’s Endless Column (1918). References abound, and Ozbolt multiplies the stylistic experiments. His work is in turn Expressionist, geometric, and kitsch, as if to prove that artists should not be tied down to a single representational vocabulary. It’s trial and error, but that’s part of the point. And for all their conceptual rigor, Ozbolt’s paintings demonstrate a contagious enjoyment of the medium. Their raw energy is beguiling.

Sarah Jones, Cabinet (II) (after Man Ray) (I) (2013).

Courtesy Maureen Paley.

Sarah Jones, Maureen Paley, closes April 19.

Roses, horses. In her sixth show at Maureen Paley, photographer Sarah Jones furthers her research on some of the topics that have long been close to her heart. Right by the entrance, a black-and-white diptych picturing an empty glass cabinet (Vitrine, 2014) announces some of the issues at play: the presentation of objects, their inaccessibility once turned into flat images, and more generally the fragile links between representation and subjects represented. Saturated with art history—Atget, Muybridge, but also Stubbs and the still life tradition—Jones’s images present themselves as fields of experimentation, her lens an acute scalpel. Her approach is pared down and systematic in an almost scientific way. But the reduced palette and forlorn flowers charge the atmosphere with a mollifying melancholia, humanizing the forensic aspect of her processes.

Sebastian Stöhrer, Ceramic (2014).

Courtesy Carl Freedman.

Sebastian Stöhrer, Carl Freedman, closes April 19.

It’s only recently that ceramic has found its way back into the contemporary artist’s toolkit. Kitschy, bulky, and embarrassingly linked to craft, it has had to wait for a respite from the art world’s fetishisation of all things conceptual—and the renewed interest in the fertile crosspollination between art and design that has come with it. The series of vessels (for want of a better word) Stöhrer presents in his first solo show at Carl Freedman is intensely physical. The clay is nothing but a trace of the hands that shaped it, the glazes tantalizingly iridescent. The works are meant to be loosely inspired by the archetypal shape of the vase, but some look more like bongs, others like penises, others still like odd little creatures crawling on their wooden-stick limbs. But all are vaguely redolent of a very 1960s-style of knickknack, perhaps nodding at the current obsession with mid-century design. Stöhrer’s creations wear their cheekiness on their sleeves. The traditional language of ceramics is twisted, transformed—made to speak now.

Miroslaw Balka, Above your head (2014,).

Courtesy White Cube Gallery.

Miroslaw Balka, DIE TRAUMDEUTUNG 25,31m AMSL, White Cube Mason’s Yard, closes May 31.

There are references aplenty in Miroslaw Balka’s show DIE TRAUMDEUTUNG 25,31m AMSL. It borrows most of its title from Sigmund Freud’s classic The Interpretation of Dreams. World War Two, the cult movie The Great Escape, Wagner, and the gallery’s altitude above sea level also come into play (as they do at Balka’s concurrent exhibition at the Freud Museum). But you don’t really need to know all this. What is most striking about this stark presentation is its ability to evoke captivity, persecution, and pain at an almost physical level, and with a drastic economy of means. Covered by a metal mesh hanging about two meters high, the downstairs gallery resembles an exercise yard. Visitors walk into this oneiric version of a penitentiary, rid of everything but its fundamental function as a human-sized cage. A whistled tune permeates the space, hopeful and haunting like the last song of the convicted. Lit from above, the lattice projects regular arabesques on the concrete floor, a fleeting motif that blends the viewer/prisoner with his gallery/jail. The effect is as elating as it is claustrophobic. For a few seconds, one might be tempted to believe that history can be felt rather than learnt.

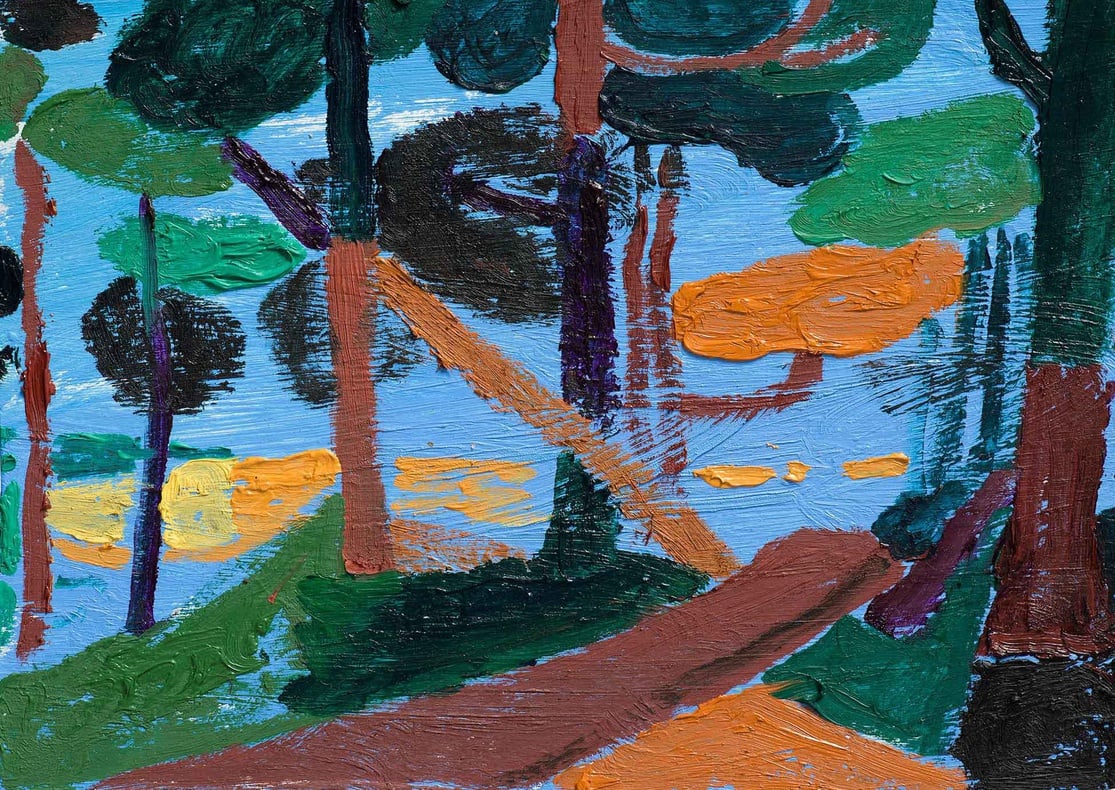

Detail of Tal R, Walk towards Hare Hill (2013).

Courtesy Victoria Miro Gallery.

Tal R, Walk towards Hare Hill, Victoria Miro Mayfair, closes April 17.

Is there still a point in painting en plein air? The question must have occupied Tal R a great deal in the summer of 2013, when, every morning, he left his summerhouse in Northern Denmark to pitch his easel in the nearby wood. With the dogged determination of a proto-modernist, he painted the same few spots day after day, always on modestly sized supports (canvas, board, paper). Thirty-seven of these works are presented here. One thinks of the young Matisse and Derain in Collioure back in 1905. Enthralled by the bright colors of the Catalan landscape, they unleashed the greens and reds that were soon to earn them the nickname of fauves (wild beasts). Tal R already had this chromatic freedom, but what he finds in the experience is the creative space, which emerges when a subject is repeated ad nauseam and learnt intimately. It might be the same broken tree, or the same fork in the road, but it’s always a different picture. Liberated from the question of what to paint, the artist can focus strictly on the how. Cezanne and Morandi also knew the trick. Although somewhat conventional—Tal R never really shakes off the fauvist ghosts—his unbridled enthusiasm in affecting. Each of these is a lesson in looking.

Detail of Giuseppe Penone, Scrigno (2007).

© Archivio Penone. Photo by Paolo Pellion, courtesy Gagosian.

Giuseppe Penone, “Circling,” Gagosian Gallery, Britannia Street, closes May 31.

Penone does Penone, nothing new here—but why deny oneself the pleasure? The relationship between the natural and the man-made, the sense of awe provoked by considering life in its rawest form, and an attempt to capture phenomena in flux run through the two monumental sculptures currently on show, just like they did, more than half a century ago, in the artist’s earlier works. But this doesn’t make them less convincing. With its fantastic expanse of brown leather molded on tree bark and covering the walls, Scrigno (Casket) (2007) is a baroque declension on the theme. Honey-colored sap appears to flow inside a split-open bronze tree, suspended horizontally across the leather. The piece’s highly-wrought aesthetic suggests some kind of magic. Yet it is simply life that Scrigno dramatizes, life and its ineluctable counterpoint, death, alluded to in the title. Visually much more restrained, the white marble Sigillo (Seal) (2008) features a cylinder engraved with abstract marks and resting on a horizontal slab, half of which is also carved with the marks. It’s as if the roll had imprinted the marble like it would an expanse of snow. For a few seconds, the properties of marble appear unsettled.

Marius Bercea, Seasonal Capital of Itinerant Crowds (2013).

Courtesy Blain Southern.

Marius Bercea, Hypernova, Blain Southern, closes April 17.

Marius Bercea’s ambitions have grown with his success. A leading member of the so-called Cluj school of painting, which also includes the likes of Adrian Ghenie and Victor Man, the painter has ceaselessly challenged his own figurative practice. The communist Romania of his childhood (and his earlier works) is still very present in this latest body of work, but new themes, and an extended palette, have started to emerge. Here, we find the Californian landscape, real and imagined. Bercea reveals himself as a colorist in these most recent works. Flamingo pinks and psychedelic oranges set his skies alight. In Suspended Animation (2013), drips of yellow paint conjure up a starry night. Bits of architecture—old and new, American and Romanian—sometimes entire cities, cram into the canvases. Occasionally, and particularly in the bigger works, so much is going on that it feels as if they could be more than one painting. Things are clearly still being worked out. But that’s price of experimentation. The painter now commands sold-out shows from London to LA; he could have easily rested on his laurels and let the cash flow in. Instead, he’s chosen to push himself into the unknown. Bercea is taking the kind of risks few successful young painters think they can afford.

Francis Upritchard, Harlequin Urn with Face (2011) and Susan (2013).

Courtesy Kate MacGarry Gallery.

Francis Upritchard, Kate MacGarry, closes April 26.

Francis Upritchard’s figures, four of which are currently on view at the gallery, are as much puppets as they are sculptures. Part medieval jesters, part hippies, they stand on their pedestals like marionettes waiting to be activated. It could be that the performance has already begun, although the connection between the harlequin Mandrake (2013), the almost Brueghelian Potato Seller (2013), and the paradoxically gloomy Allegro (2013)—hair wrapped around her neck like a noose—remains tenuous at best. Upritchard delights in this narrative ambiguity. She doesn’t tell a story, but carves out a space for stories to surface. This is complexified by the vessels she introduces in the display, some of which, such as Harlequin Urn with Face (2011), bear human features. Made with the same modeling material as the main figures, they introduce further doubts: Are these characters in their own right or mere utilitarian ancillaries?A lower class of being? Or is the artist poking into our often emotional relationship with objects? No answer is forthcoming, and that’s precisely the point. Uprichard invites her viewers to follow her into her imaginary world, and then leave them there alone to make sense of it all.

Installation view of “Life Model” (2014) by David Shrigley.

© the artist. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London. Photo: Stephen White.

Study from the Human Body, Stephen Friedman Gallery, closes April 26.

The human form as a subject might well date back to the birth of art itself. Study from the Human Body looks at its expression in the work of contemporary artists including Stephan Balkenhol, Kendell Geers, and Yoshitomo Nara and is anchored by two modern giants: Francis Bacon and Henry Moore. Too wide a theme to allow for the construction of a precise curatorial discourse, the show nonetheless demonstrates the endurance of its appeal. David Shrigley’s immersive installation Life Model (2014), in which members of the public are invited to draw a larger-than-life, blinking and pissing, misshapen nude male doll, debunks myths of classical beauty. Even the most talented draftsman could only produce a caricature. Tom Friedman presents a Giacometti-esque version of himself, a grotesque Goliath made of painted Styrofoam balls. But, at times, the link seems feeble. Granted, Yinka Shonibare’s mannequin Fire (2010) involves a body, but the body itself isn’t what the sculpture is about. Likewise, Huma Bhabha’s totem-like Chain of Missing Links (2012) has as much to do with clichés of the primitive as it has with the human form. But it could be that, formal preoccupations aside, the body always has something to do with everything else, the culture it inhabits, the history that preceded it, and the normality into which it is shoehorned. It’s a vessel, shaped and transformed as in Catherine Opie’s portraits of members of the transgender community (Vaginal Davis, 1994), the locus of existential questioning as in Paul McDevitt’s selection of drawings Notes to Self: 5 March 2013. The Study from the Human Body is also a study of everything beyond it.

Installation view of the Upper Room at David Zwirner featuring works by Michael Dean and Fred Sandback in the exhibition, “Sharing Space” (April 5–May 17, 2014).

Courtesy David Zwirner, London.

Michael Dean and Fred Sandback, Sharing Space, David Zwirner, closes May 17.

The pairing of Michael Dean with Fred Sandback is one so immediately obvious when seen, it’s as if it were meant to be. And yet it could seem as if the young British and the late American legend have very little in common. Dean explores the relationship between language and sculptural form with cast concrete pieces often based on actual words. Sandback subtly highlights and isolates spaces with thin lengths of acrylic yarn. But together they sing, two distinct voices instinctively falling in harmony. Each influences the viewer’s perception of the other. The concrete pieces appear lighter, more ethereal, while anchoring Sandback’s installations. Simultaneously, those energetic lines lift up the space, adding a sense of movement and dynamism to Dean’s creations. Transgenerational exhibitions have become very popular of late, but they are rarely as satisfying.