Art World

Is Steven Soderbergh’s Ludicrous, Boozy Website a Work of Art?

The "retired" filmmaker’s image appears ceaselessly on the site.

The "retired" filmmaker’s image appears ceaselessly on the site.

Paddy Johnson

“I am always on the lookout for a spark of necessity—a feeling that this particular artist had no choice but to make this particular artwork this particular way.” Art Critic Roberta Smith told the New York Times’s Jan Benzel in 2008. The critic was describing how she decided what to write about, but it doubles as a description of an element of good art. It’s a thing brought into the world, for no other reason than because the artist needs for it to exist.

Smith’s words come to mind when paging through Hollywood director Steven Soderbergh’s personal website, Extension 765, which often reads like an art project more than it does a hobby or pastime. Soderbergh describes the website as a “portal to the outside world,” and its tagline is “a one-of-a-kind marketplace.” It is filled with eccentric products—exposure tests (on Polaroid film) from his early films, T-shirts, an Ocean’s Thirteen mouse pad, even press-kits (the one from Girlfriend Experience is going for $50) that aren’t necessarily intended to make money. Like any artist project this website exists for no other reason than because the artist felt compelled to make it.

Navigating the site, it’s hard not to cast Soderbergh’s past accomplishments and interests onto what we see. It was his masterful and artful sensibility that brought us Traffic and Out of Sight. Even a scrap of that here—and I think it exists—would be further evidence of his brilliance. And of course, because the director has been threatening to leave the film world for years so he can focus on his painting and pursue other endeavors (Behind the Candelabra (2013) was finally declared to be his last film before retirement), one assumes this website is amongst his more creative pursuits.

The website does not present itself as art, though it does reference it. In the art section he sells photographs, but issues the disclaimer that he’s offering them up as opposed to his paintings, “because some of them are quite big.” “I’m not sure the Internet is the best place to display stuff like that,” he quips. You get the sense that he thinks your browser can’t handle the size of his JPEGs.

The point is moot though—like the working retirement of Maurizio Cattelan, Soderbergh, too, is semi-retired—he’s stopped making film and he already announced this year that he’d given up on his plan to paint (he had only declared that he was leaving the film industry to paint full-time in August 2011).

The things up for sale on Extension 765 are organized by quirky market-ready headings. For the purposes of this article, I will cover the sections I had the most to say about: Threads, Booze, Art, and Salon des Refusés.

In Threads, a slew of T-shirts are on offer, and boy, are they ever nerdy. One shirt sports a logo for Tres Cruces Western Fidelity Bank, a location in the movie Charley Varrick (1973). Another shirt, 18 LU 13, is the license plate number of the car—a Lincoln MK III—used to smuggle heroin in William Friedkin’s 1971 film The French Connection. Within Threads, a disclaimer puts the buyer on notice that “all of the T-shirts we offer now will, at some point in the future, become unavailable.” The warning comes in response to a previous T-shirt debacle where he did not anticipate the demand for his T-shirts and ran out.

Salon des Refusés: An occasional drop of creative detritus from the closet/hard drive of The Artist Soon To Be Known As Steven Soderbergh is better. It is a blog laid out by posts organized by calendar dates, in which we see diaristic notes on films Soderbergh has seen lately, one short video made of images that are either art or look like art, and various films, altered and remixed. The header, Salon des Refusés (Salon of the Refused), references the famed 1863 salon of Impressionist paintings rejected by the Paris Salon and appropriately, this section of the marketplace has little to no monetary value—much like the work in the original salon.

Within Salon des Refusés, under the September 22nd date is “Raiders,” my favorite post thus far. It begins with a four-paragraph screed on how movement, timing, and shot-order move a viewer through a film. As a means of showcasing this, Soderbergh presents the 1981 adventure flick Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark in its entirety, turned black-and-white, and overlaid with the instrumental soundtrack from the The Social Network created by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross. We are immediately aware of the film’s staging. For example, about eleven minutes into the film, when Indiana Jones (“Indy”) is confronted by rival archaeologist René Belloq and the indigenous Hovito people over an idol he has in his possession, a version of Edvard Grieg’s celebrated orchestral work In the Hall of the Mountain King begins to play. We see a sequence of quick reaction cuts amongst the natives before they chase Indy through the woods. Shots resemble the flow of the music—as a viewer, you can’t help but study the visuals.

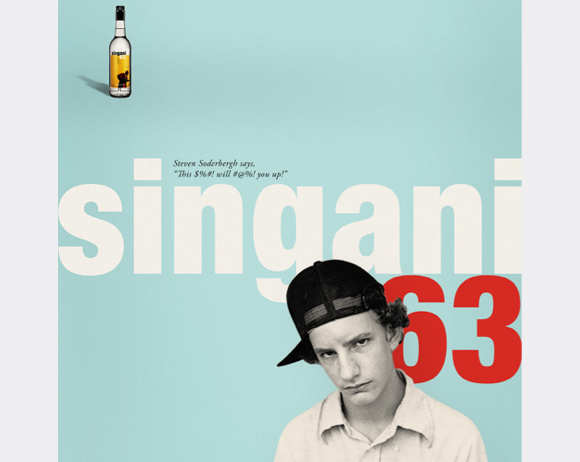

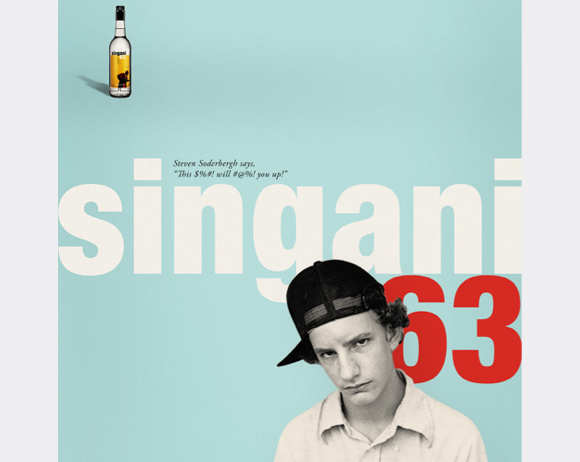

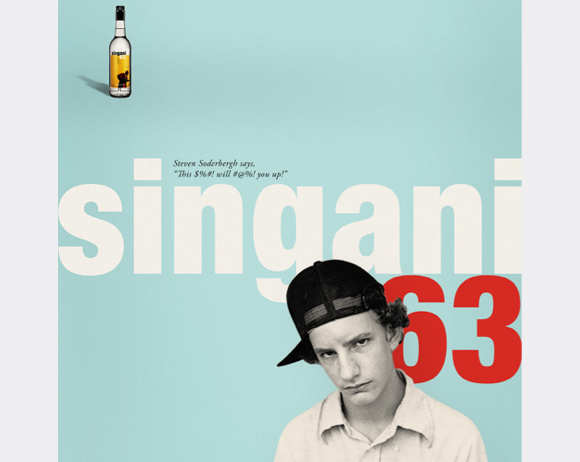

That the video so elegantly achieves the aims of its creator makes it a success. But it’s not the only victory of the site. Enter Singani 63. A “privately-funded project known as The Steven Soderbergh Adventure,” Singani 63 is a white liquor drawn from grapes harvested nearly 6000 feet above sea level. It’s more commonly known as Cachaca, the sauce used to make Brazil’s national cocktail, the Caipirinha—and it’s the most unique and unexpected of all the goods up for sale. Booze nerds seem to love Soderbergh’s drink. (I haven’t tried it yet.)

Its marketing is brilliant. For example, the liquor’s label headings include quips like: Origin=Bolivia, Destination=your mouth, Class=high. These are inscribed with the signature of “Mr. Dr. Soderbergh.” Recipes show Soderbergh behind the bar, in full bartending garb.

Decisions like that seem a little closer to the kind of personal branding that fuels the Internet than they do art. Unlike many art projects where artists are loath to place their image anywhere near the work, Soderbergh’s image appears ceaselessly on the site. Still, self-awareness and irony are the lifeblood of many artists’ careers, and because the decision to produce a Brazilian liquor in the first place seems so deliberately random, it’s hard not to think of the company as made with an awareness of art.

Oddly enough, the work on the site that most closely resembles art in its conventional sense—a series of unique framed and matted Polaroids within the Art section—is the weakest. For $750 you can purchase these “exposure tests” from Soderbergh’s earlier films. A picture of Catherine Zeta-Jones lounging on a chair in Traffic is already sold, but a shot of Viola Davis peering through a door in Solaris is still up for grabs. For $1000, you can purchase a print scanned from a digital file and converted into a black-and-white print.

Exactly what you get is a little nebulous. Images of the photographs are too small to discern their quality, and digital-to-analogue photographs (of later films like Side Effects and Behind the Candelabra) are issued in an unspecified edition.

“Full disclosure,” writes Soderbergh, “the subjects of these Polaroids have not been contacted, mostly because I’m sure they would ask to see them all before I put them on sale, and there are hundreds of these things (we’re only posting six at a time to save space) and it would be way too much hassle and why would somebody want to hold me up when I’m trying to give money to Children’s Aid?”

Normally, a statement like this would annoy me—it’s goodwill for selfish reasons—but since the entire website seems never to have been meant to be more than a personal project, it’s hard to get worked up about it.

I don’t think the website itself is art—it’s a wireframe to present a few projects and thoughts rather than a medium used to test its own biases—but some of the individual projects are created with an awareness of art, and would benefit from the label. His film alterations, for example, are genius, and would easily create a buzz were they displayed in a gallery—with or without his name attached.

Extension 765 exists purely because Soderbergh felt the spark of necessity, and I’m glad for it. It has given me insight into his particular vision as a filmmaker. And unlike most other art, I can at least afford his T-shirts.