Art & Exhibitions

Is the Populist ArtPrize Becoming . . . Snobby?

The world's most unprofessional art contest should not be professionalized.

The world's most unprofessional art contest should not be professionalized.

Alexandra Peers

A reporter walks into a bar…and everyone inside is arguing over “What is art?”

If it sounds like the beginning of a joke, it’s not. That’s what happens every year in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Every fall, the metro area of slightly over a million people 150 miles east of Detroit surrenders itself—to an even greater degree than Miami does every December—to art. Local hotels, restaurants, public buildings jostle to get artists to display in their spaces. Art is everywhere, in over 600 locations in the city: murals, installations, street-corner monuments—even sculptures on string float by. It’s ArtPrize, the world’s largest art contest, open to virtually anyone and decided by popular vote, something of a Midwest Miss-America-Pageant–meets-Thunderdome of art. For three weeks, local TV and front-page newspapers cover art as the lead story with intensity, respect and rigor. (For an art worlder, for one brief shining moment, this is Camelot.) It is a marvelous experience, and if you fancy yourself part of the arts community, you’ve got to go at least once.

The sixth annual ArtPrize extravaganza is September 24 to October 12 this year, and there are big changes, and not necessarily for the best. Has it sort of gotten . . . snobby?

To explain: The event, founded by local Amway heir Rick De Vos, features work by about 1500 artists from around the world and always awards a highly lucrative first prize to the people’s choice—this year $200,000. There’s always also a tasty but less lucrative juried prize, for good measure, awarded by a panel of art experts. (The two bodies rarely agree.) The jury usually has some big art world thinkers you would trust with such things: Jerry Saltz and Anne Pasternak of Creative Time in the past, the respected Susan Sollins of Art21 this year. But for the first time this year, the choice of the “professionals” will earn the same amount, $200,000, making the win something of an anti-climactic tie and footnoting the public’s choice. Have we “separate-but-equaled” the ArtPrize?

If so, that’s a shame. ArtPrize is the only event of its kind in the world, and that uniqueness is far more interesting than any emerging star that could rise out of it, even one picked thoughtfully and with all good intent by perceptive art world jurors. Indeed, there’s something deliriously crazy about ArtPrize: the Turner, Hugo Boss, Golden Lion, and Bucksbaum prizes are all peanuts compared to the money won by the creator of the “People’s Choice” in Michigan. The debate fuels and empowers an entire town and packs the Grand Rapids Museum of Art, which shows contenders it has backed. “From parking garages to public parks, museums to bridges, every inch of Grand Rapids transforms into a hub of creative expression,” ArtPrize’s literature brags. How wonderful.

So how come the jury prize has been upped this year? Some contend (though I don’t agree) that, by and large, in its first five years, the public has shown cringingly bad taste. What is largely true that the trophy has gone to oversize, complicated works of technical skill—in some cases, one might even say craft—that aren’t necessarily things you’ve never seen before, just versions of them exceptionally well-executed. A goodly share of the finalists have been artworks of giant animals—think a larger-than-life lion made of nails, a dog assembled of metal junk, a wall-size winsome polar-bear portrait, elaborately accurate elephant drawings, a big wooden pig. Simply put, minimalism and abstraction have few fans at ArtPrize. Open Water No. 24, the artwork that won the first ArtPrize in 2009, is a 19-foot long oil painting by Brooklyn artist Ran Ortner that has almost a trompe l’oeil effect, with foamy black waves spilling out at the viewer.

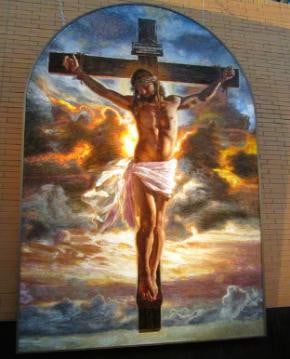

Mia Tavonatti, Crucifixion, 2011. Stained glass mosaic won the 2011 ArtPrize award in Grand Rapids, Michigan. (Some rights reserved.)

Consider perhaps the most controversial of all grand prize winners, 2011’s Crucifixion by Mia Tavonatti. To the art crowd, in which pretending to be secular is a religion, the elaborate life-size stained glass mosaic of Christ on the cross at sunset was too saccharine, over-the-top, emotional. The palate had echoes of (shudder) Thomas Kinkade. But, on the flip side, the piece was so reviled, even Christian Century magazine panned it, noting it managed to “combine the worst of petty Christian religiosity with the squishy imprecision of the “God-in-the-sunset crowd.” Ouch. For good or ill, it spoke to thousands of people.

Esquire magazine, in a 2012 look at the prize, was even meaner. “Critics (Tip to readers: whenever a journalist starts a sentence with “critics,” it means he agrees with them.) have derided ArtPrize as a naked bid to buy cultural cachet in a flyover-country backwater, and fans have hailed it as radically open, a populist wresting of aesthetic judgment from the snobbery of elites in New York and Los Angeles.”

That obnoxious “flyover-country backwater” line is what gives the art world a bad name. But of course the most ridiculous thing in that sentence is that we value the aesthetic judgment of anyone in Los Angeles. Just kidding. You see how snobbery can just stop everything short?

The Grand Rapids extravaganza was started by the grandson of Richard De Vos, cofounder of Amway. Various members of the extended family have been major Republican party donors, Republican party candidates or, in the case of an uncle, founder of Blackwater, the private military services firm. Mr. De Vos is perhaps not entirely without economic motive in his beneficence: He owns one of the town’s two four-star hotels (the Amway), which is now booked solid for much of every September.

But motive aside, what he’s dreamed up is potent and unprecedented. The stats for the last version of ArtPrize: 1,524 artists; 169 venues; 47 countries and 45 states or territories; 49,078 voters placing 446,850 votes. (In the first round, registered voters 16 and older can cast “thumbs up” ballots for multiple artworks.) This year’s promises to be more inclusive, with free public transport from many neighborhoods surrounding the city, accessible paths for wheelchairs and multilingual literature likely to boost voting to an all-time high.

Is that a good thing? Yes. The masses are often wrong, except when they are right. Charles Dickens and Andy Warhol are just two geniuses who achieved popularity before critical respect. And who’s laughing now?

Personally, I hope the public and the professionals both pick something the art world will hate. Bring on the giant pandas.