Art & Exhibitions

Kai Althoff Gets Too Wrapped Up in Nostalgia at Michael Werner

A critical take on the New York-based artist's London show.

A critical take on the New York-based artist's London show.

Coline Milliard

It could be the backroom of a long-dead dressmaker. Two mannequins, clad in 1920s frocks, preside over a mess of musty cloth covering the walls; another dummy has been toppled over. Hippie-ish jumpers are scattered about; sparse furniture and intriguing tools lie around. Then one clocks in the paintings: deep brown, bottle green, and anthracite pictures, which speak of art history frame after frame. Kai Althoff doesn’t do “painting shows,” just as the New York-based, Cologne-born artist doesn’t simply paint, but also produces music, garments, and performances, in the self-confessed hope of being “culturally autonomous.” His exhibitions are conceived as immersive environments, as invitations to step back in time. Even the installation shots of the show on the gallery’s website (but made unavailable to journalists) seem to come from another era. At Michael Werner’s London gallery, like in most of Althoff’s shows, the destination is vague, but the nostalgic frisson guaranteed.

If Althoff’s dummies are the lead characters of this theatrical set, than the paintings appear at first to function as backdrops: sometimes ornaments, sometimes glimpses into other scenes, other places. Here, a Brueghelian woman kisses her lover as she climbs down (or up?) a ladder. There, a parent supervises a child’s homework (both works Untitled, 2013). There’s something satisfying, refreshing even, in seeing painting relegated to a supporting role. But the illusion doesn’t last. The more time one spends in the space, the more one realizes how much the props, mannequins, and accessories that initially seemed so crucial are only flourishes in a traditional painting display. It is telling that, jumpers aside, the props aren’t listed on the gallery’s checklist of works on view. Their purpose is to give the ensemble an edge, to wrap the paintings up in pretend irreverence.

This doesn’t make the pictures themselves any less good. Put bluntly, Althoff is a fantastic painter. His matt, muddy paint is deftly controlled. His muted palette, rich with endlessly subtle variations, conjures up scenes at once remote and familiar: kids playing in the street around an antique-looking buggy (Untitled, 2014), a woman in yellow dress as if swallowed by the similarly-hued background (Untitled, 2012), ghostly faces emerging from abstract surfaces (Untitled, 2014). The characters in Althoff’s images are governed by their own rules, their own logic, none of which is ever made explicit. Looking at these is like looking at world unfolding behind a thick glass pane, tantalizingly out of reach.

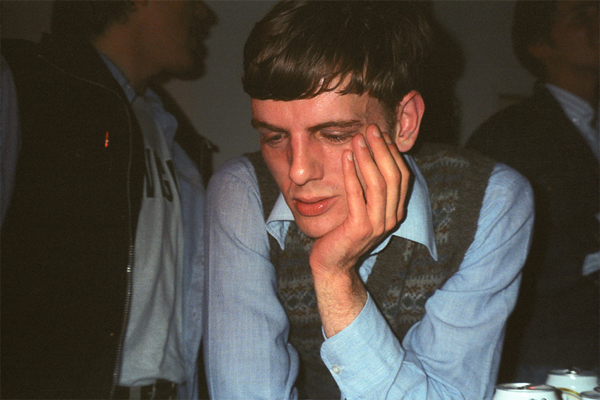

Kai Althoff at Michael Werner, London

Photo: © Coline Milliard

While the remoteness is alluring, the paintings’ familiarity is more problematic. Althoff is a chronic referencer. Names keep rushing in: there’s Gustav Klimt, Marc Chagall, Blue Period Picasso, and the German Expressionist Emil Nolde, with whom the artist is most-often associated. It makes for a comfortable viewing. The brain clicks into a well-oiled gear. No need for assessment, what it’s looking at has long been vetted. Post-modern irony would be a tired position to adopt, but it at least would somewhat clarify the artist’s relationship to the historical material he so abundantly draws upon. Instead, Althoff’s post-post-modern earnestness renders unclear what exactly he’s bringing to the table. Considered without their distracting three-dimensional trimmings, his paintings feel overtly reverent, verging at times on derivative.

One piece stands out from this referential quagmire. Presented in the exhibition’s first room, a large color-drawing (again Untitled) is by far the freshest piece on display, precisely because it doesn’t immediately bring another artist’s work to mind. It concentrates the viewer’s attention onto itself—and there’s much to consider. Drawn over nine sheets of paper—as if Althoff had started with a vignette and constantly found himself needing extra paper space—it pictures a tall, blond woman. She’s holding a pencil and a brush, perhaps posing as a double of the artist. Right next to her, a clown-esque figure, his head covered with a blood-red helmet and sporting a harlequin necktie, holds a blanket that covers a large swathe of the piece with a patch of wavy, blue and green abstraction.

Two sub-scenes involve members of an Orthodox Jewish community. There’s a group of men crowded at the feet of the female artist and looking up with a frown on their face. On the bottom left-hand side corner of the piece, a young man holds some sort of weapon, or tool, in front of another one, whose head is thrown backwards in pain, or ecstasy. Althoff spent over two years on this work, reveling in the minutia of his exquisite technique, and the dreamscape it summons up. The allusions to elements of Althoff’s own world—the communities in his neighborhood of Crown Heights, Brooklyn, the angst that often comes with the decision to live with a brush in hand—position the piece squarely in the now. This drawing seems to open up an exciting, new conceptual space for Althoff, freed from the phantoms of the past that have haunted him for the last thirty years. But only the next show will tell if it’s the one he’s choosing to embrace.