Art & Exhibitions

Hello To 80-Year-Old Dorothy Iannone and Her Sex-Fueled Retrospective

How explicit are the artworks of 80-year-old Berlin-based artist Dorothy Iannone? Quite.

How explicit are the artworks of 80-year-old Berlin-based artist Dorothy Iannone? Quite.

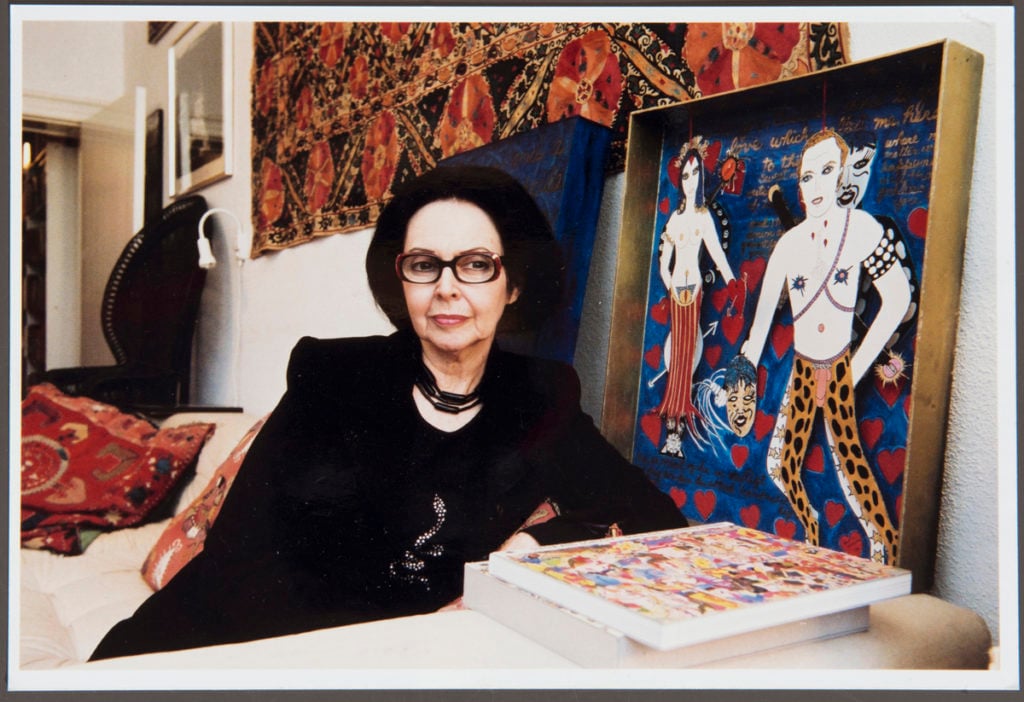

Alexander Forbes

With all it’s princes and kings, does the art world or even the culture at large have a need for a dominant grand dame? The post-recession years have seen a mounting interest in works by female artists who have already departed this earth or are well along in years, artists such as Geta Bratescu, Alina Szapocznikow, and Dorothy Iannone. The latter’s oeuvre is now being feted with a large-scale retrospective at the Berlinische Galerie. Now 80, the Boston-born, Berlin-based Iannone has been making art since the late 50s, first in the US and more prominently in Europe. Yet her autodidact, non-academic status and often controversial, even censored motifs left her in the margins until recently. Now represented by Air de Paris and Peres Projects and having enjoyed an exhibition at New York’s New Museum in 2009, Iannone’s stock is increasingly on the rise.

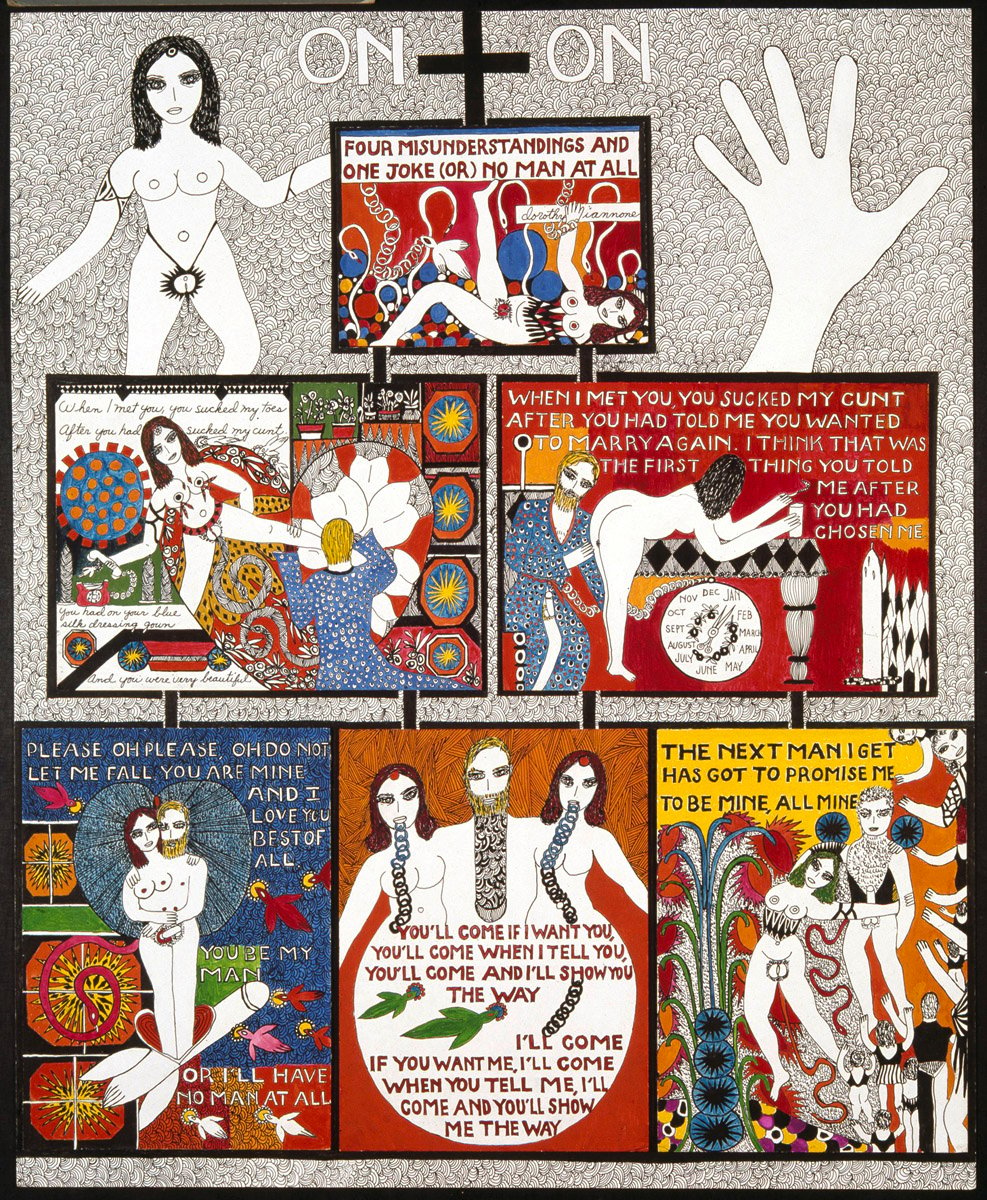

The approximately 150 works on view across the Berlinische Galerie’s ground floor both provide a road map to Iannone’s central themes—female sexual autonomy, ecstatic love, and a slightly mystical worldview—and a surprise about her relatively tame beginnings seen in the early works on view. The paintings shown in the exhibition’s first two rooms pull from the abstract expressionist movement that subsumed her during New York’s postwar years. Yet Iannone’s use of primary colors and rigid structure in such pieces as Southern Façade (1962) or Sunday Morning (1965) recall Mondrian or patterned textile design and quilts as much as they bring to mind the machismo-soaked, gestural works of Ianonne’s contemporaries.

Dorothy Iannone, Southern Facade (1962)

© Dorothy Iannone, Photo: Jochen Littkemann

It’s in Sunday Morning that Iannone’s penchant for including text in her works emerges, her first definitive step toward what later becomes a distinguishing element of her oeuvre. Perhaps owing to her collegiate background in English and American Literature, she writes in lyrical prose, such phrases as: “Why should she giver her bounty to the dead? What is divinity if it can come only in silent shadows and in dreams?” The words hint also at a growing use of religious tropes in expressing her secular (what some might even classify as blasphemous) themes.

On the opposite wall, hanging behind an early example of the painted furniture that Iannone has also created throughout her adult life, In the East My Pleasure Lies (1965/2013) represents a rare use of photography in Iannone’s practice. Double exposures of her bust and another three-quarter length shot form the center of a highly detailed ink drawing also featuring fragments of text—the copy shown is a multiple. More significant than its use of photography, however, is her engagement with her own biography and annals of personal experience from that point forward.

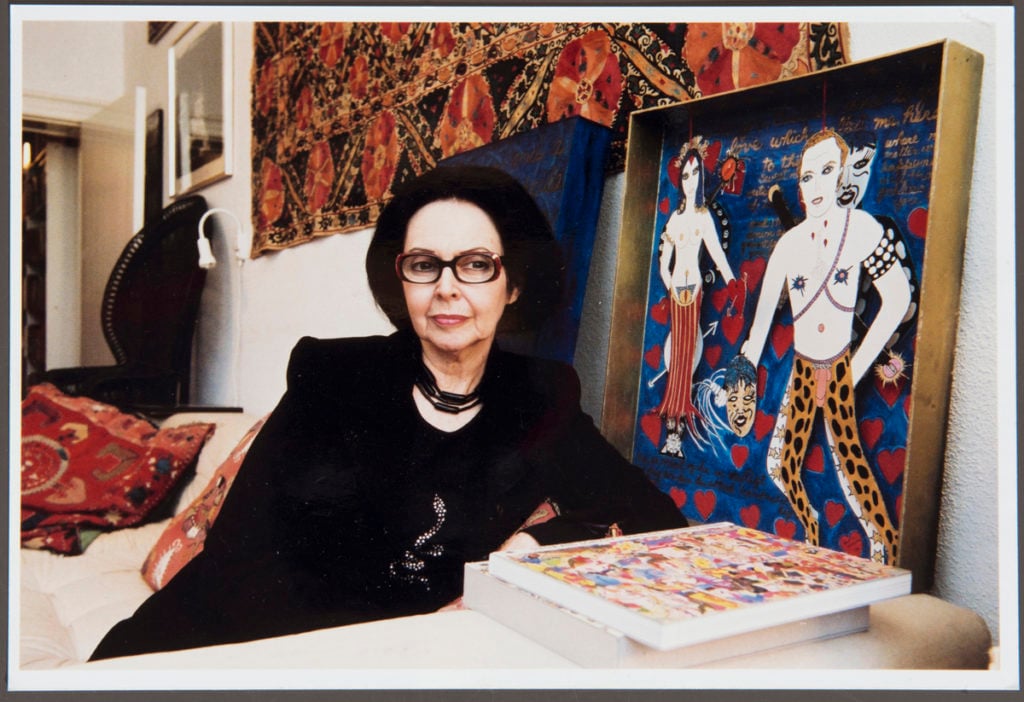

Dorothy Iannone, On And On (1979)

© Dorothy Iannone

Exemplary of her full embrace of this turn is her 48-part work Icelandic Saga (1978, 1983, 1986). Each drawing in the series appears as if a frame from a comic strip or page from a (rather adult) picture book. Other series like Dialogues (1967-68), The Berlin Beauties (1977-78), and paintings like On and On (1979) take up a similar organizational motif. They chronicle Iannone’s trip with her then-husband, painter James Upham, and poet and visual artist, Emmet Williams, to visit Dieter Roth. Then based in Reykjavik, the Fluxus artist and Iannone soon struck up a romance, resulting in her swift split with Upham and move across the pond to Iceland and later Düsseldorf. The corresponding text has an almost scriptural quality, as if there was some predestination to her and Roth’s meeting. But it stays shy of the teleological, with enough dry wit and, at other times, almost girlish epistolary prose inserted to assure the reader/viewer that passion is more strongly at play than God in her progression.

The piece—and others from this period such as her People series of cutout wood figures—mark a turn to the explicit in Iannone’s work. Representations of genitalia and to a slightly lesser extent, intercourse, are featured in nearly every piece from the late 60s onward. In Iannone’s depiction, testes and vulvae are near identical. It’s likely a nod to her balancing of the sexes and emphasis on the importance of physical and emotional unity as a means of enlightenment rather than a more overtly political stance of upending patriarchal hierarchy. Likewise, the dialogue between her and the male figure—most often Roth—is a ping pong of the dominant sexual role: her “Suck my breasts, I am your beautiful mother” for his “I have got such a marvelous cock,” both also titles of paintings from 1970-71 and 1969-70, respectively.

Dorothy Iannone, People (figures from the series of the same title) (1966/67)

© Dorothy Iannone

With Roth as muse, Iannone’s explicit works grew in scale and moved increasingly to canvas. However, her color palette and the pictures’ flat surfaces remain. Censorship quickly became an issue due to the works’ highly sexual content. Ahead of a show supposed to take place at Harald Szeemann’s Kunsthalle Bern, authorities proposed to censor the nudity and sex she depicted in the works set to go on view. Both Iannone and Roth pulled their pieces from the show and Iannone recounted the experience in a Fluxus publication, The Story of Bern, or Showing Colors (1970).

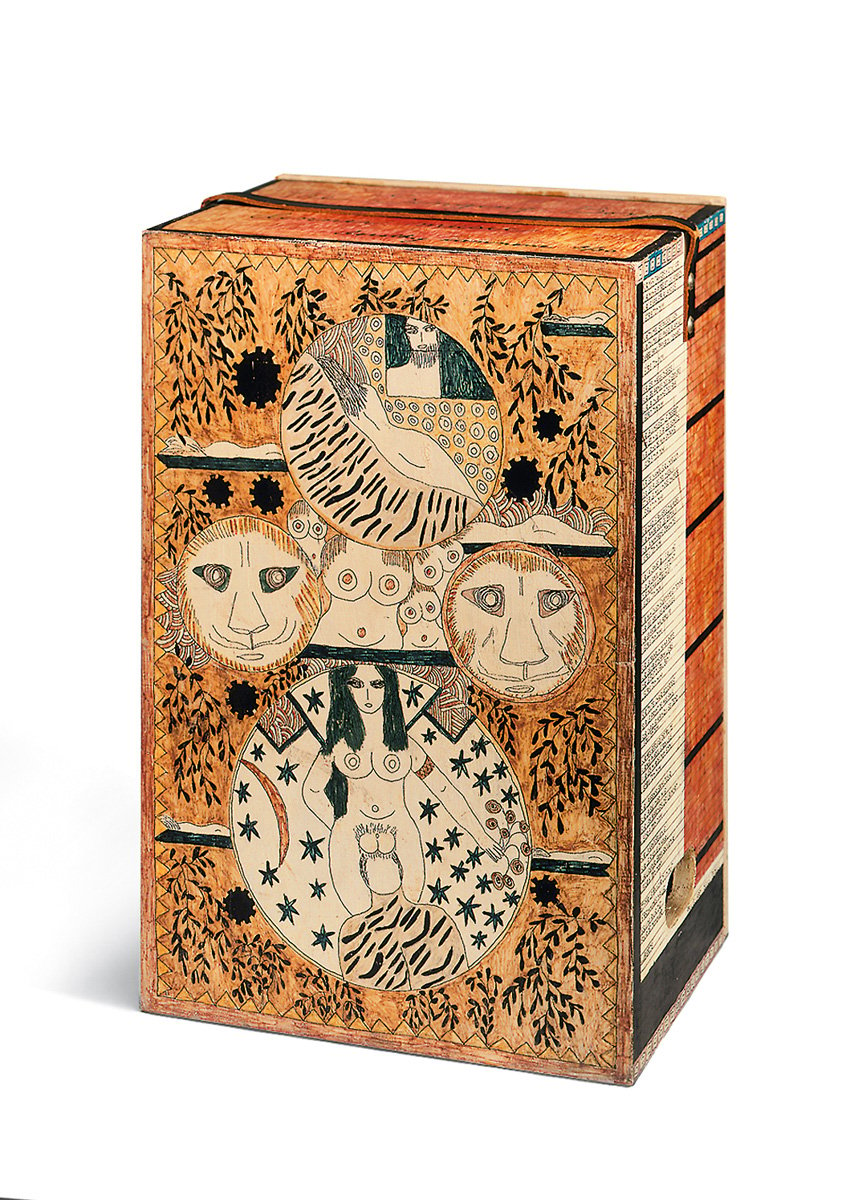

The lack of such prudishness in contemporary society (or at least contemporary art) has allowed Iannone’s work to come forward out of the shadows. However the Berlinische Galerie’s exhibition does present a conservative head at least once. Most of Iannone’s so-called singing boxes blare loudly. Some of Iannone’s finest, the works see a speaker placed inside a wooden box, which she painted with her characteristic figures and text, often including the lyrics to the songs she said she would often find herself bursting into in heady times amongst friends. Her voice, non-traditional in its warbling alto, is nonetheless enchanting. One such sound and video–based work, I Was Thinking of You (1975), features a video and audio recording of Iannone masturbating to climax. During the opening, her utterances turned heads. Upon a subsequent visit, however, the work was all but muted, only able to be heard when within a few inches of the sculpture.

Dorothy Iannone, Singing Box (1972)

© Dorothy Iannone

Does it take detract from the exhibition as a whole? Not really. In fact, the gesture serves as a reminder of what might have led Iannone’s oeuvre to become so fascinating to contemporary eyes in the first place. Through the twists in her biography, Iannone was allowed access to her time’s defining movement, Fluxus. But she was forced to walk forward her practice in all but a vacuum of public perception due to censorship and the very fact that she had settled in Berlin long before it became a subject of intrigue for the international art circus.

For so much of her life, making art was as much a personal release as it was any official attempt at forging a career. And even still, the art world is of little interest to her. She has largely shunned interviews and the press since gaining prominence in her own right. Her devil-may-care attitude toward the public and the resulting genuineness of her art offers refreshing repose outside of our often over-professionalized field of contemporary artistic experience.