Art & Exhibitions

Takashi Murakami Enters His Skull Period at Gagosian

The founder of Superflat offers a post-disaster belief system.

The founder of Superflat offers a post-disaster belief system.

Ben Davis

What’s going on with Takashi Murakami? The superstar Japanese artist, best known for his “superflat” spin on anime aesthetics in paintings featuring toothsome mutant characters of his own invention—not to mention for his brand reinvention of Louis Vuitton and BFF status with Kanye West—is now painting… gnarled old men and piles of skulls?

In truth, there are two things going on at once in “In the Land of the Dead, Stepping on the Tail of a Rainbow,” as the artist’s ambitious new Gagosian show is called. On the one hand, this is Murakami on a renewed Serious Artist kick. The 28 paintings and sculptures in the show include what you’ve come to expect from Murakami: colorful, crisp-edged cartoon paintings and goggle-eyed monsters. But amid all that there is a newfound emphasis on Buddhist themes and a troubled subtext relating to the still-fresh trauma of the horrifying 2011 earthquake in Japan, which killed some 16,000 people, touched off a nuclear crisis at Fukushima, and left the country in shock. Gagosian’s press release touts Murakami’s new show as proposing “a contemporary belief system, constructed in the wake of disaster, that merges earlier faiths, myths, and images into a syncretic spirituality of the artist’s imagination.”

Since what you will see is, in fact, not particularly reverent seeming, some background may be necessary. The presiding influence here is the Japanese painter Kano Kazunobu (1816-1863), whose epic cycle of 100 images of the Buddha’s disciples (“arhats”) was painted in the wake of another disaster, the 1855 Edo earthquake. Kazunobu’s images of the arhats plunging like superheroes into a fantastical underworld to rescue the damned were meant, in the words of James Ulak, who curated the cycle at the Freer-Sackler in DC, to “let his audience know that the mercies of the Buddha were there even for the suffering.”

Visitor looking at Takashi Murkami’s In the Land of the Dead, Stepping on the Tail of a Rainbow (2014) at Gagosian Gallery

Photo: Ben Davis

In many of the stranger paintings here, Murakami is riffing on this iconography, and the new works’ most striking new figures—a rogues gallery of inventively deformed wisemen—are a reference to Kazunobu’s wild religious fantasies. The arhats get their most memorable outing in the show’s title painting, an insanely detailed 80-foot-long panorama depicting a skull-spangled netherworld filled with capering wizards, rainbow-colored waterfalls, a languishing toad king, and tiny humans adrift on sailboats amid the unfurling chaos.

Yet if Murakami is making a play for a new sobriety, at the very same time he’s still the quintessential impresario, looking to out-compete his fellow artists in the Spectacle Olympics. The artist has said that another inspiration for the show was wanting to do something as splashy as Damien Hirst’s super-scaled replica of an anatomy doll, Hymn (2000) (perhaps not uncoincidentally, skulls are also Damien Hirst’s signature motif, his shortcut to art-historical credibility and punk gravitas). The Gagosian exhibition features, alongside other crowd-pleasers, towering, monstrous replicas of Buddhist temple statuary; a 56-ton, walk-in simulation of a Japanese sacred gate; paintings awash in gold and platinum leaf; and The Birth Cry of a Universe, a golden tower of drooling, blobby mutants.

![Installation view of “In the Land of the Dead, Stepping on the Tail of a Rainbow,” with Embodiment of Um (2014) [foreground]](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2014/11/IMG_0280.jpg)

Installation view of “In the Land of the Dead, Stepping on the Tail of a Rainbow,” with Embodiment of Um (2014) [foreground]

Photo: Ben Daivs

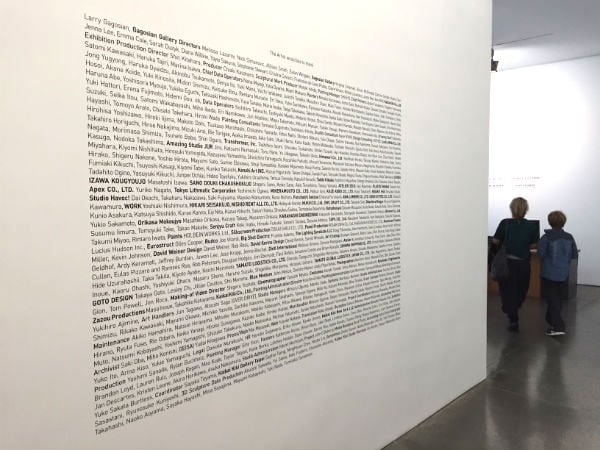

Overall, the impression left by this show is that it represents a feat of extraordinary engineering, an unsettling new synthesis of elements, and an impressive attempt to break out of a successful formula to claim new territory. Of course, you could say the exact same things about the new Doritos flavor of Mountain Dew. And much like “Dewitos,” Murakami’s Gagosian show comes with a long list of mystery ingredients: Posted by the entrance is a massive block of text naming all those involved in the show, which Murakami claims is his biggest production to date. It includes a small army of “Painting Managers,” “Painters,” and “Painting Consultants” (up to 150 painters, he says, working around the clock in shifts!); a squadron of “Chief Data Operators” and “Data Operators;” “Design Consultants;” “Silkscreen Production;” “Costumes;” even a “Graffiti Consultant.”

Acknowledgements for Takashi Murakami’s “In the Land of the Dead, Stepping on the Tail of a Rainbow” at Gagosian

Photo: Ben Davis

Never underestimate the allure of caffeinated Dorito flavor though! This show is fun, and actually has the merit of rooting Murakami’s psychedelic cartoon style in the esoteric fantasies of Japan’s rich art history in a new and clever way. It’s just that, ultimately, the art seems more designed to provoke people to take cellphone pics than it does to reflect on the Great Tohoku Earthquake or “the role of faith amid the inexorable transience and trauma of existence” (that’s the press release again).

Takashi Murakami, I Hate Death (2014)

Photo: Ben Davis

A small introductory gallery features a pair of small, skull-patterned canvasses, similar to the dense patterns of mutant flowers that Murakami has created in the past. The words “I Hate Death” are spraypainted atop the pattern, in English (reminding you that, despite the artist’s turn to Buddhist symbolism, he has been very explicit about his strategy of targeting a Western audience). That’s not the deepest message in the world—but then again, this is the artist who invented an art movement he called “superflat.” Murakami’s working some new angles, but he’s still up to his old tricks.

Takashi Murakami, “In the Land of the Dead, Stepping on the Tail of a Rainbow,” is on view at Gagosian Gallery, 555 West 24th Street, New York, through January 17, 2014.