Art & Exhibitions

What On Kawara’s Analog Wisdom at the Guggenheim Has to Offer a Digital World

Ahead of his time, Kawara was the bard of metadata.

Ahead of his time, Kawara was the bard of metadata.

Ben Davis

Installation view of “On Kawara: Silence” at the Guggenheim

Photo: Ben Davis

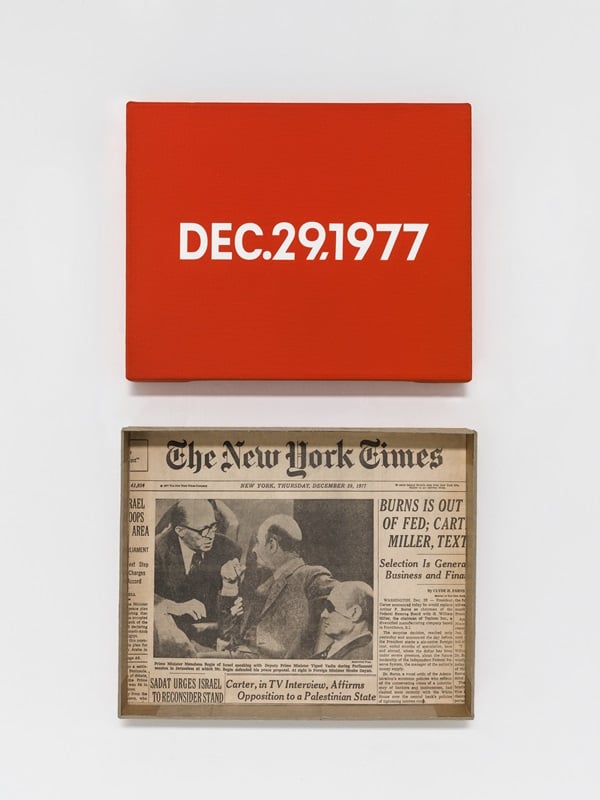

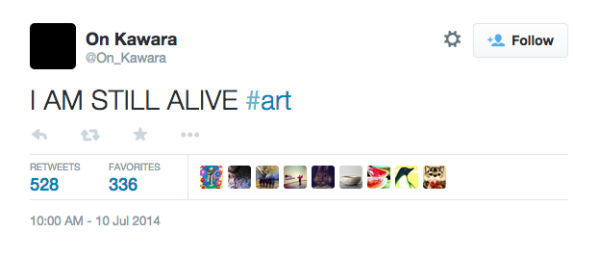

In 2009, @on_kawara flickered onto the scene. The Twitter account, whose profile picture is a black square, simply tweeted out once a day, “I AM STILL ALIVE #art,” in homage to one of the most well-known projects by the great Conceptual artist On Kawara, who, starting in 1970, sent telegrams to friends stating, over and over again, “I AM STILL ALIVE.”

On Kawara, Telegram to Sol LeWitt, February 5 (1970)

Photo: Courtesy LeWitt Collection

I thought of @on_kawara briefly at the opening of “On Kawara: Silence,” the Guggenheim’s just-opened retrospective. Clearly, @on_kawara is a gimmick, while Kawara himself is one of the true greats, but it at least shows how his demanding and cerebral art chimes with a certain contemporary way of thinking. Filled with his signature “Today” paintings—austere panels, each proclaiming the date they were made in stark white text against a plain colored ground—and lots and lots of paperwork documenting Kawara’s various projects, this show might feel more like doing taxes than must-see museum entertainment to a lot of people. Yet it deserves to be savored, and one way into the work is to consider just how ahead of his time Kawara feels: He was making art about the “quantified self”—the contemporary self-improvement craze for tracking and charting one’s personal data—not just before the fitbit, but before the handheld calculator.

On Kawara’s “Today” paintings, installed at the Guggenheim

Photo: Ben Davis

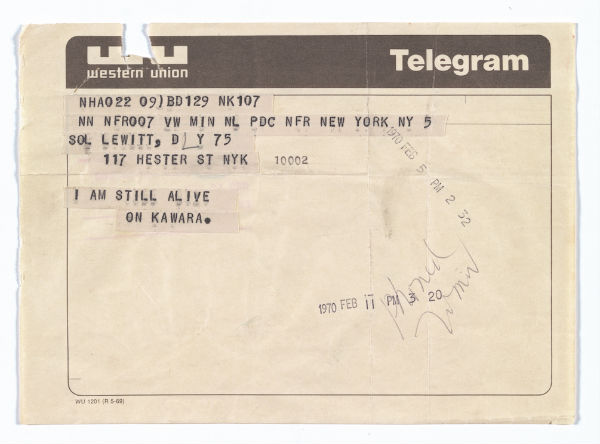

By all accounts, Kawara was an interesting guy. He was born in 1933 in Japan, and came of age in the smoldering post-war period, achieving early notoriety in Tokyo as an artist steeped in the day’s mordant political surrealism (none of the works from this period, sadly, make it to the Guggenheim). In 1959 Kawara moved to Mexico, where according to Rubén Gallo he painted a now-lost mural of the plumed serpent Quetzalcoatl and was enough a part of the scene that he was featured in a show of young Mexican painters that travelled to Colombia. There was also a formative trip to France in 1964, which inspired some suggestive early drawings. A wall of these make it to the Gugg, looking somehow precise but indistinct, full of tables of phrases, spidery charts, and opaque diagrams, like sketchbook pages from an alien reconnaissance mission.

On Kawara, Paris–New York Drawing no. 144 (1964)

Photo: Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London / Collection of the artist

This personal background hardly matters though, because when Kawara hit his creative stride in the mid-60s as part of the international outbreak of Conceptual art, the key animating energy came from the uniquely indirect way he fused his work with his own biography. Kawara never gave interviews, and did not explain his work; the rigor of his reticence is quite amazing, and must have required some effort given his ultimate fame. In effect, it was a kind of negative performance. At the same time his work is all about himself. He spun art out of existential metadata—not the content of his life but its wreaths of attendant information—and his art ends up being about both how little and how much you can know from such stray facts, a half-century before the subject became a political hot-button issue in our epoch of data paranoia.

This may sound anachronistic, but it’s actually striking how Kawara anticipates some of these themes. Take the “Today” paintings, begun in 1966, generously surveyed in various clusters up the long Guggenheim spiral. These are the product of Kawara’s personal invented ritual—he worked in a limited set of colors and sizes, and in a standardized format (in the very earliest paintings, you can see him experiment with different fonts, a stutter-step that hits home how consistent he became thereafter), destroying them if they were not finished by the end of the day there described. In essence, they home in on the timestamp as a form of self-expression.

On Kawara, JAN. 4, 1966 “New York’s traffic strike.” New York (1966)

Photo: Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

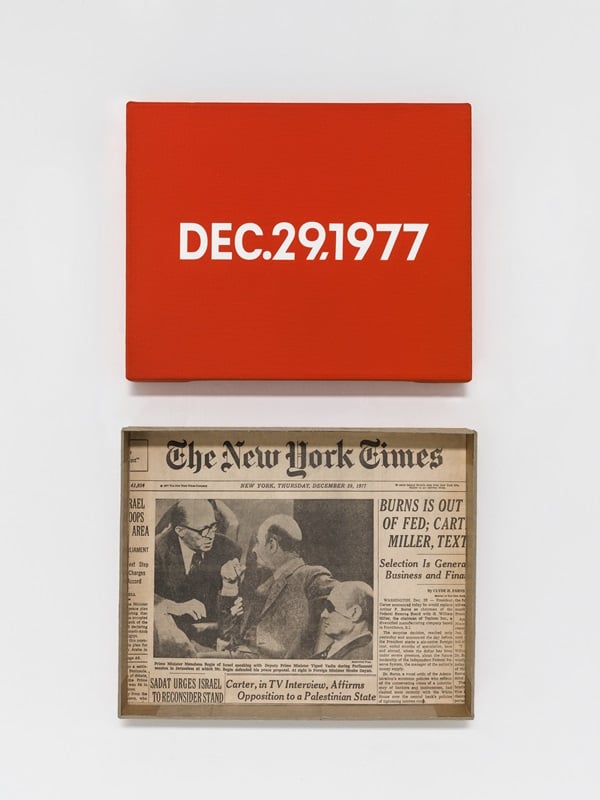

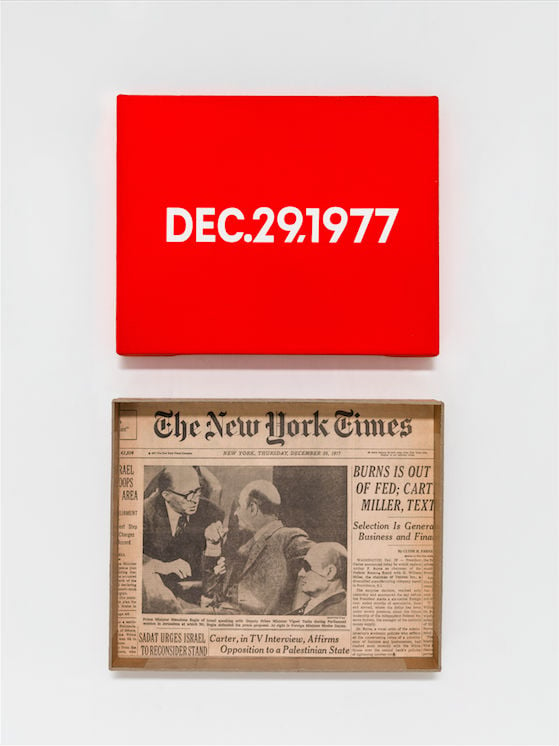

What can you tell from a timestamp? Not much, but also a lot. Many of the “Today” paintings were packed in a special box, each lined with a page of the day’s newspaper from wherever Kawara happened to be. Presented as part of their display, these remind you of the historical lifeworld surrounding the creation that you can reconstruct from the simple date. In another quirky flourish, Kawara renders each painting’s date, always, in the language of the country he is visiting, as if tempting you to read the assembled chronology as a coded history of his own path through the world. With some minimal data and knowledge of the procedure that produced it, you can reconstruct an entire life.

On Kawara, DEC. 29, 1977 “Thursday.” New York (1966–2013)

Photo: Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London, Private collection

Other works make this theme still clearer. “I Met” (part of a trio of routines he engaged in from 1968-1979) amounts to a simple, type-written diary of everyone Kawara met each day, one page per day. It is really nothing but an inscrutable series of lists, and yet it is also the raw material to map out his social network. Without knowing anything more about the man, you would likely infer that “Hiroko Hiraoka” was his companion, since her name recurs most often, in much the same way you could track who was romancing whom by stalking their Snapchat “Best Friends.” One striking “I Met” entry is dated “24 Mai, 1977” (the language suggests that he was in France), which is blank—Kawara met no one that day. Which tells you nothing, while at the same time telling you quite a lot.

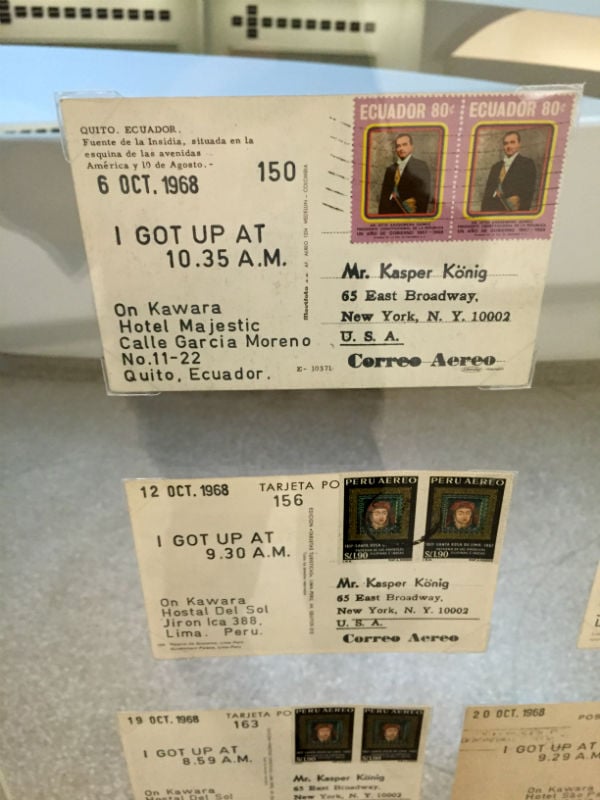

Works from On Kawara’s “I Got Up” series, installed at the Guggenheim

Photo: Ben Davis

Or consider “I Got Up” (also 1968-1979), for which the peripatetic artist sent a postcard to a different friend each day, stamped simply with a sentence stating the time he woke up. Surveying this correspondence displayed at the Guggenheim, you begin to reconstruct an idea of this man’s daily routine, noticing patterns and anomalies (just what did he do on August 16, 1969, the night before he woke up at 5:47 pm?). Since the actual content is so sparse, the postcard-based works also get you thinking about what you can guess about someone from a review of the peripheral details of their correspondence: return addresses, whom he writes to and how often, the kinds of stamps he chooses. (Discovering familiar names among the addressees gives an air of vicarious glamor to it all: Lucy Lippard, the dealer Kasper König, the artists Michael Asher and John Baldessari, and so on).

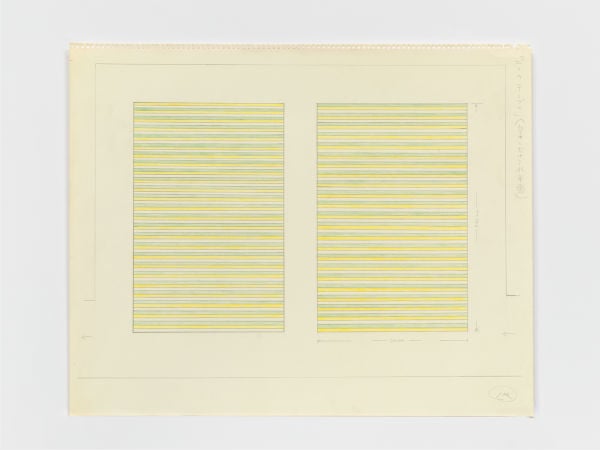

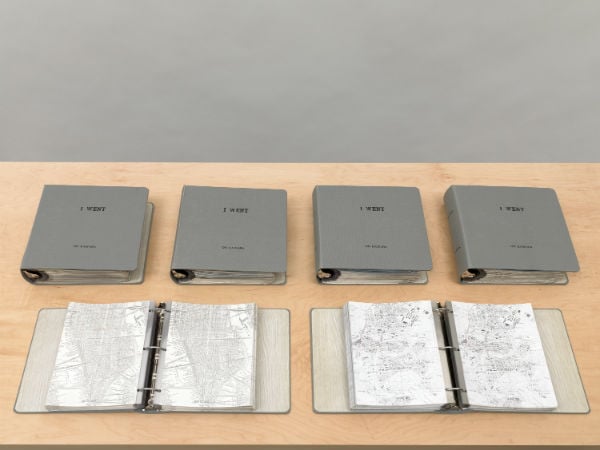

On Kawara, I Went (1968–79)

Collection of the artist

Throughout Kawara’s career, there’s a kind of simple joy in meticulous collection of facts. Consequently, the pleasure of “On Kawara: Silence” is partly nostalgia for the innocence of data. For “I Went” (the third part of this trilogy of rituals), Kawara simply traced out where he actually went upon a map of the city he found himself in each day. They are displayed at the museum beneath glass, artifacts of a vanished moment in more than one sense. In an age of surveillance—both government (the NSA’s boundless data-collection) and corporate (Uber’s boast that it can track your one-night stands)—the imagery is not so innocuous or purely quirky anymore.

On Kawara died on July 10, 2014. On that day, the Twitter-bot @on_kawara continued on, serene, unphased, undead; there were simply more retweets. It continues to this day.

Tweet from @on_kawara, from the day of the artist’s death

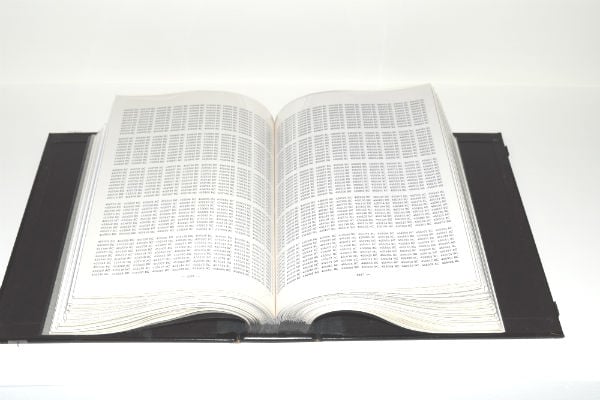

This juxtaposition makes me think a final thing about On Kawara’s prescience: He not only anticipated an obsession with personal data, but because he was rooted in another world, offers an alternative way of thinking about it, a possible model for how to stay human amid it all. We are obsessed with personal testimony, and he is too, but he also stepped back from it to let its silences speak. We are obsessed with the present, and he was too, but he infused his work with a wry awareness of how vanishingly small the present is in the immensity of time: “One Million Years” (1970-1998), a set of leatherbound tomes, does little more than catalogue dates of a too-big-to-imagine period, 500 to a page, 10 to a line. We could do the same now with a keystroke, but we might not think about what it means to us as humans.

Book from “One Million Years” at the Guggenheim

Photo: Ben Davis

The greatness of Kawara’s work is that it is all about mindfulness, about living in the present deliberately, not leaving the trails of evidence that one leaves behind uninspected, or taking the mechanics of life for granted. Because when your last “Today” painting is painted, you are gone.

“On Kawara: Silence” is on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1071 5th Avenue, through May 3, 2015.