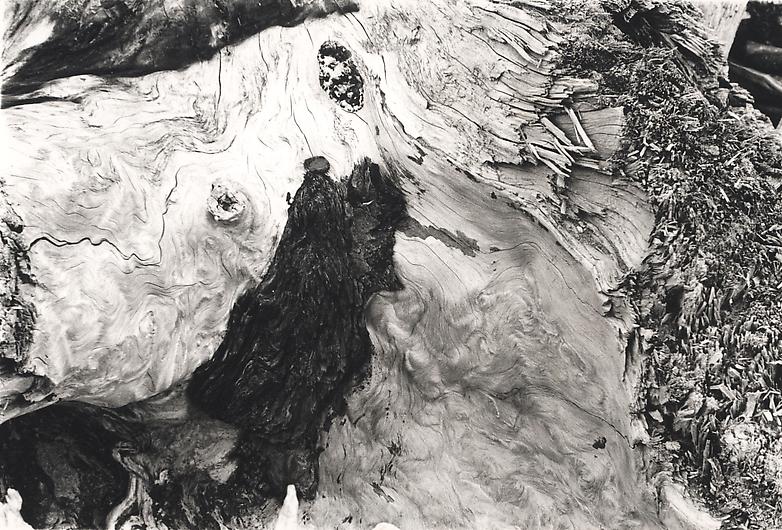

Jay DeFeo, Untitled (1972).

Courtesy Mitchell-Innes & Nash, © 2014 the Jay DeFeo Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Mitchell-Innes & Nash, Jay DeFeo, closes June 7.

Long reduced to a footnote of 20th century art history, DeFeo (1929–1989), previously remembered largely for The Rose (1958–66), her monumental, massively thick relief painting, came roaring back into the public consciousness with her impressive 2012–13 retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Her current show at Mitchell-Innes & Nash continues the trend with a selection of DeFeo’s 1970s experiments in photography, an assortment of drawings and collages, and her late-in-life return to oil painting. DeFeo’s distinctive exploration of form and repetition of shape, as well as her fascination with space and depth of field, are seen throughout the exhibition. Limited to a largely gray-scale palette, save for a few sepia-toned works, the show has Dadaist undertones, especially in DeFeo’s still life photography. De-contextualized close-ups of pedestrian items like a head of cauliflower or a kitschy seashell lighting fixture take on an unsettling, almost otherworldly quality, reminding the viewer of DeFeo’s uncanny ability to create the illusion of texture and three-dimensionality even in her flat works.

Sarah Cascone

Turi Simeti, Trittico Neri Con Ovali in Progessione (2011).

Courtesy De Buck Gallery.

De Buck Gallery, Turi Simeti, closes June 8.

Striking in its simplicity, Simeti’s “The Primary Form of Painting” presents a series of minimalist black or white canvases. Each features a number of ovular protrusions that lend the work a sculptural quality. The mysterious properties of the strangely bulging and puckering canvases almost compel you to reach out and touch. The artist’s manipulation of the surface of his paintings has been his signature throughout his nearly half-century-long career, which began as part of the Zero movement of the late-1950s (other practitioners included Lucio Fontana, Yves Klein, and Hans Haacke). Simeti’s work benefits from being shown as a group. Seen en masse, the paintings’ commanding physical presence demands careful attention, as the subtle differences between the canvases make themselves known slowly.

Sarah Cascone

Greg Smith, Breakdown Lane (2013), video still.

Photo: courtesy Grinnell College, Iowa.

Susan Inglett Gallery, Greg Smith, closes June 20.

The starting point for Smith’s current solo exhibition is his film Breakdown Lane (2013), which is described as depicting a “dystopian road trip,” and, despite the presence of numerous functioning cars, seems meant to imply some sort of post-apocalyptic future. The elaborate set pieces, shown on video in uncomfortable close-ups, have taken over the gallery space, obliterating the white cube with a large canvas tent adorned with lawn chairs, car bumpers, charred wood, and other assorted re-purposed materials. The assemblage is a visually arresting yet tone-deaf appropriation of the thriftily cobbled together, necessity-is-the-mother-of-invention-borne ramshackle shantytowns constructed by the world’s homeless and displaced.

Just as Smith’s video fails to capture the grim sense of hopelessness generally associated with solitary protagonists struggling to survive on the remnants of a fallen civilization, his colorful shack seems more akin in spirit to a child’s fort than a real dwelling place. His choice of materials and incorporation of crafting techniques such as quilting seem motivated by artistic desires rather than any functional utility, which casts doubt on his avowed narrative. Similarly, Smith’s jury-rigged car, which he operates from the backseat through the assistance of a mirror, comes off as a smart-alecky experiment, not a makeshift fix for a technical problem. Is this a game? The product of a disturbed (or at least highly eccentric) mind? While you question Smith’s intentions, you can’t help but be awed by his exotic vision.

Sarah Cascone

Kerstin Brätsch, installation view at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise.

Photo: Thomas Müller, courtesy Gavin Brown’s Enterprise.

Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, Kerstin Brätsch, closes June 21.

One of three artists currently showing at Gavin Brown, Brätsch’s wall-sized paintings radiate a monumental and faux-naive complexity, making it impossible to reduce them to any single definition, “abstraction” included. Similar in many respects to the organic shapes created by oil spills, or the ghostly faces visible in wood grain, Brätsch makes apparitions visible through such painterly techniques as marbling, which gives her work a mysterious and unsettled texture. The paintings seem to present something new each time you look at them, as though the figures Brätsch indistinctly renders were watching you watch them. The eerie sentience pervading these large-scale works makes them feel vaguely religious, but in a contemporary way that more closely resembles vital intoxication.

Jeffrey Grunthaner

Lisi Raskin, Recuperative Tactics, installation view, Art in General, April 2014.

Photo: Stephen Probert.

Art in General, Lisi Raskin, closes May 31.

Raskin’s Recuperative Tactics uses a wooden wall installation as a backdrop for works in diverse media, from crafts, to video, to lectures, to events. A process-oriented social practice work that is added to constantly, Raskin’s installation reflects her intention to open out her space to artists in need, giving them a place to make work (if they can’t afford studios) as well as a place to exhibit, while also serving as somewhere issues surrounding labor, gender, economy, and related matters can be discussed. Given its socially inclusive nature, Raskin’s installation tends to become a fete, such as when Girls Write Now, a community of women writers, hosted “WRITE / CODE / SPEAK,” which celebrated young girls who expressed their experience of maturing into life through multimedia works.

Jeffrey Grunthaner

Daniel Turner, “PM” installation view.

Photo: Courtesy the artist, Team Gallery.

Team Gallery, Daniel Turner, closes June 1.

Composed of three sculptural works at once reminiscent of agricultural feeders, kitchen counters, and operating tables, Turner’s show “PM” invokes a psychological subtlety that relies heavily on the placement of objects and the spareness of means used to produce them. The menacing character of the exhibit derives not only from the creepier-than-life, coffin-like appearance of two sculptures, colored an underwhelming yellow and paralleling each other in the front room of Team Gallery’s Grand Street location, but from the fact that their bays are browned in places by water erosion, while they lack both a drain and a faucet. In the back room, there’s a sort of table the size of a human body, too low to the ground to actually be a table, on which rest two refrigerator handles. The handles seemed to have been placed there purposefully, but this purpose remains obscure, and the dimensions of the table ward off any tactile engagement.

Jeffrey Grunthaner

Blane De St. Croix, Dead Ice (2014).

Photo: Courtesy Fredericks & Freiser Gallery.

Fredericks & Freiser Gallery, Blane De St. Croix, closes June 14.

For De St. Croix’s first solo show in New York, the American artist’s massive installation—a curved structure that looks at once like a breaking wave, part of a boat hull, a glacier, and on the underside, a snow- and ice-covered boardwalk—takes up almost the entire front room of the gallery. In the second room are two wall-hung collages that at first look like textured, mountainous sheets of ice, but which are actually cut, layered pieces of white paper with intricate ink drawings. In a lengthy essay penned by curator Joseph D. Ketner II, as well as the gallery press release, we learn that last year De. St Croix, concerned with global warming, conducted extensive research in the Svalbard Archipelago in the Arctic Circle, exploring abandoned mining towns, traveling on ice breakers, and going on aerial flyovers. There is an in-depth description of “dead ice” as a scientific term for what happens when a glacier ceases to move, and melts in place, shedding ice. But there is little or no connection apparent between this intriguing-sounding subject matter and the works that are on view. Using just a few of the gorgeous, expansive photographs on the gallery invite and artist’s own website documenting his travels would have provided much needed context, or at least a better visual backdrop.

Eileen Kinsella

Lee Bul installation view, Lehmann Maupin, Chrystie Street.

Photo: Elisabeth Bernstein, courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong; Lee Bul at Lehmann Maupin LES; and Rothko prints at Pace.

Lehmann Maupin, Lee Bul, closes June 21.

At the opening night of Korean artist Lee’s fourth solo show at Lehmann Maupin, her massive, mirrored installation Via Negativa II (2014) stopped viewers in their tracks as they stepped into the main gallery and tried to take it all in, circling the outside of the structure, or viewing the space-age, shack-like structure from a higher vantage point on the gallery’s second floor. Yet, the experience of stepping inside the narrow labyrinth of fragmented infinity mirrors and the equally reflective mirrored floors is even more intense and disorienting than one would expect, forcing you to move cautiously (hence the reason only one or two visitors are permitted inside at a time).

Meanwhile Lee’s swirling, kinetic sculptures resembling futuristic cityscapes are hung from the gallery ceiling and reflected in the mirrored floor. I can’t say I’m familiar with the “tenets of apophactic philosophy” that Bul’s work alludes to, according to the gallery’s press release. But I have no problem with the explanation that it centers on the belief that “divine nature is beyond the understanding of the rational human mind and can only be comprehended by defining what it is not—‘the negative way’—rather than what it is.” It seems apropos for such a heady trip.

Eileen Kinsella

Mark Rothko, Untitled (1944–1946).

Photo: courtesy Pace Gallery © 2003 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Pace Gallery, Mark Rothko, closes June 21.

The first-ever solo show of Rothko’s Surrealist-influenced watercolors from the 1940s—packed with biomorphic forms that evoke Miró and Dalí—will likely be a revelation to observers who only know his luminous color field paintings featuring floating blocks of color. Though not immediately identifiable as Rothko paintings, this is a serious, accomplished body of works that evidences a vast, impressive array of color palettes and techniques. Each is distinctive and complex enough to invite and reward careful study. The show evolved from a Pace exhibition last year, “Mythology,” about the genesis of abstraction in American art through mythological themes. “We saw a growing interest in this period of Rothko’s work,” said Pace president Marc Glimcher. Several discussions with Rothko’s children, Kate and Christopher, led to more research, which then became focused on Rothko’s watercolors from this period.

Eileen Kinsella

Maroesjka Lavigne, Excavator, On the Road (2011).

Photo: Courtesy Robert Mann Gallery.

Robert Mann Gallery, Maroesjka Lavigne, closes May 17.

Some words for Ísland, or Iceland as it’s written in Icelandic: hoarfrost, white-hot, névé. And now, some pictures for Ísland, each of them on display at Robert Mann Gallery. Here work by the young Belgian photographer Lavigne, who (according to press materials) drove alone across Iceland for four months, evokes the kind of world that a 19th-century snowshoe-clad loner could love—spare, brightly lit, and miles from cities jammed with multi-story filing cabinets stuffed with people and their belongings. Snowmen, Reykjavik (2011) shows a circle of sun-faceted snow menhirs (clean white) foregrounding a lone soccer goal on a grassy field, a line of blue water and, farther in the distance, ghost-white houses. Phantom, Krossneslaug, Westfjords (2011) has a man just below the surface of a glacial pool, the dapple of light and liquid erasing his facial features. A Kelly green Excavator, On the Road (2011) raises the question of what Iceland needs to clear away in order to develop. Perhaps some precincts of the world deserve their blank spaces, Lavigne suggests, deserve to be left to themselves and their own quiet thoughts—like the faraway-eyed young woman in Hildur in Her Car, Mosfellbaer (2012), or the individuals taking the thermal waters in 2011’s Blue Lagoon, Reykjavik. Or artists.

Elizabeth Manus

Chaïm Soutine, Brace of Pheasants (c. 1926).

Image: Courtesy Paul Kasmin Gallery.

Paul Kasmin, Chaïm Soutine, closes June 14.

This exhibition, the first of a series at Kasmin examining Soutine’s works, is a transporting experience. A painter of the École de Paris—Jewish artists who lived and worked in Paris circa 1910 until about 1920 but were not French (and thus eluded inclusion in the École Française)—Soutine was an ardent admirer of Rembrandt, particularly his paintings of animal carcasses. Here he has his way with dead rabbits, fecund no more, and yet they cast such vitality. Lying body-scalped on a table, one rabbit’s remains looks momentarily like a pile of live roses. Soutine’s colors, even after years of time, are rich—actually impart a feeling of amplitude. His whites conjure meringues, some of his blues are the hue of a robin’s egg. The impasto of the oil on canvas Landscape at Céret (circa 1921–22) lends a sculptural quality that not only conveys emotion, but also (as Eric Kandel’s catalogue essay points out) places us at the artist’s side as he works, allowing us to “‘feel the texture of the paint’ with our eyes” and “almost see the actions of the artist’s hand.”

Elizabeth Manus

Fred Tomaselli, Nov. 9, 2011, 2013.

Courtesy James Cohan Gallery.

James Cohan, Fred Tomaselli, closes June 14 (book signing May 10).

Can I just say: I want what Fred Tomaselli is having. I don’t mean gouache or archival ink or anything like that. When my Times arrives each week, I want to gaze into the featured photo (above the fold) and have some kind of seer’s experience. Isn’t this what Tomaselli does with what he calls (in the Prestel book on the subject) his capriccetti—“brief, larkish, improvisational excursions”? They are running jumps through, well, current events as selected by the editors of the paper of record and manipulated to the point of pyscho-kookiness by Tomaselli. His “Current Events” series now numbers more than 90 front pages, and many of them are here on view at Cohan in all their radiant, supercharged trippiness. Eyes multiply on Bernie Madoff’s face; Spanish soccer players wear skulls for heads, after a victory; Silvio Berlusconi’s eyes resemble C-3PO’s and come with radio waves. These colorful Times works resemble Tomaselli’s large-scale works in spirit. The artist’s 72 x 72 inch photo-collage Penetrators (Large) (2012), an acrylic and resin work, shows a bird with a long sword-like beak in the mouth of a well-toothed, presumably venomous viper. Which creature will deliver the mortal puncture is anybody’s guess—unless what’s taking place is a mutant kiss. You tell me.

Elizabeth Manus

Michael De Feo, Oh So Very Bloemen (2014).

Bleecker Street Arts Club, “The ’80s: Past + Present,” closes May 31.

Curated by influential collector Keith Miller, this show is a trip back in time to the 1980s, when Pop art ruled and street art was making its way onto gallery walls. With works by Ronnie Cutrone, Michael De Feo, CRASH, Tom Slaughter, and Scott Kilgour, the show is accessible, exciting, and evocative of a more democratic moment in New York’s art history. Notable works include De Feo’s drippy flowers, just in time for spring, and Cutrone’s flourescent drawings of Pop icons like Mickey Mouse and the Smurfs.

Cait Munro

Joris Laarman MX3D (Dragon Bench) (2014).

Courtesy Friedman Benda.

Friedman Benda, Joris Laarman, closes June 14.

Anyone with an interest in 3D printing will want to visit this show by Laarman, a Dutch designer. Several thematic explorations are evident here, most notably “Maker furniture,” aesthetically pleasing furniture built from high-quality materials in printed pieces that fit together like a puzzle; and the “Spirographic series” of sculptures created using a robotic 3D printer that can draw lines in space. The accompanying video of this process will revolutionize your preconceived ideas about what 3D printing looks like.

Cait Munro

Gabi Trinkaus, Human after all.

Courtesy Claire Oliver Gallery.

Claire Oliver Gallery, Gabi Trinkaus, closes June 24.

Trinkaus’s birds-eye portraits of cityscapes, countrysides, and everything in between appear to be flawless photos from afar, but closer examination reveals they are in fact intricate collages of words and images clipped from glossy magazines. Akin to the experience of playing with Google Maps, the works offer a shift in perspective when viewed close up or from a distance, and the dark, dramatic, label-laden city portraits lie in stark contrast to those of tree-lined suburban streets. They are works you want to sit with for a while, if for no reason other than to pick apart the complexities of the thousands of strips of paper that come together to depict our world.

Cait Munro

Guy Goodwin, Chicken Finger Palace (2014).

Photo: Benjamin Sutton.

Brennan & Griffin, Guy Goodwin, closes June 1.

In spite of their very analog materials—acrylic paint in bold primary tones on layers of stapled-together cardboard—there’s a distinctly high-tech sensibility to Goodwin’s paintings, which evoke heavily processed foods and the landscapes of 8-bit video games. Like the walls of a padded cell in a psychedelic mental institution, his embossed surfaces and overlapping clumps of color seem enveloping with their protruding edges. The bright cardboard mounds hover vibrantly against their monochrome backdrops, fitting into one another like puzzle pieces for a supremely satisfying effect.

Benjamin Sutton

Marie Lorenz installation view at Jack Hanley.

Photo: Benjamin Sutton.

Jack Hanley, Marie Lorenz, closes May 18.

A five-channel video documenting Lorentz’s practice, which is devoted to exploring the wilderness at the city’s fringes, is tucked into her installation of dock pilings, which fills Jack Hanley’s space from wall to wall and floor to ceiling. Exploring this dimly lit, forest-like environment—one punctuated by mysterious, ritualistic artifacts cobbled together from driftwood and trash—turns gallery-goers into cohorts of the women in Lorentz’s post-apocalyptic video, Ezekia, who are exploring the garbage-strewn shores of a ruined city. Presented in this transporting setting, her end-times urban archaeology takes on a mystical, practically transcendental gravity.

Benjamin Sutton

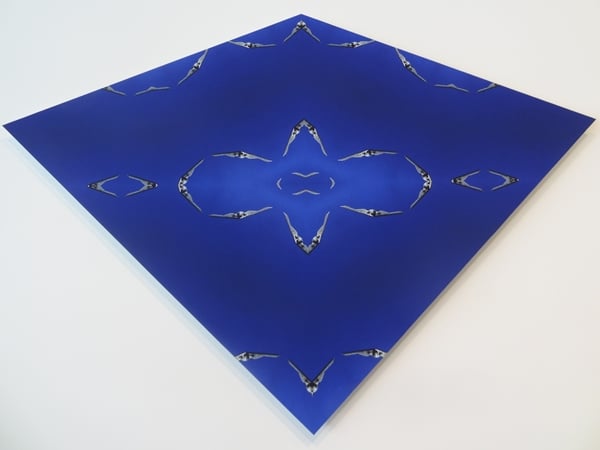

Sanaz Mazinani, Royal Stealth (2014).

Photo: Benjamin Sutton.

Taymour Grahne Gallery, Sanaz Mazinani, closes May 24.

The Iranian-Canadian artist’s works are filled with news media images of military jets, missile explosions, soldiers, and suicide bombers, though you don’t realize it at first. She deconstructs, reassembles, and arranges these appropriated images of warfare into dazzling photo-mosaics. Superficially, they evoke the traditional mosaic patterns of Mazinani’s native Iran, but, more insightfully, they demonstrate how desensitized we’ve become to this type of visual material, how easily such disturbing and politically charged imagery can be reduced to abstract and aesthetically pleasant patterns. The resulting works, cut and arranged in abstract geometric forms, alternately seem ancient—as in the image of fireworks over a US military cemetery endlessly repeated in Howitzer and Fireworks (2014)—and creepily futuristic, like the diamond-shaped pattern of stealth bombers in Royal Stealth (2014).

Benjamin Sutton