Market

Art Law on Recovering Your Art

New York's highest court addresses those attempting to recover long-absent art.

New York's highest court addresses those attempting to recover long-absent art.

Ronald D. Spencer and Judith Wallace

This essay updates When Is It Too Late to Recover Artwork You Own? Laches: The Stealth Defense, published in the winter 2012/2013 issue of this journal. New York’s highest court addresses those attempting to recover long-absent art and those defending claims from the distant past.

• • •

When Is It Too Late to Recover Artwork You Own? Laches: The Stealth Defense, published in Volume 3, Issue No. 3 of this journal, examined the defense of “laches,” which is intended to prevent unfairness resulting from the assertion of long-delayed claims. The laches defense has two elements: (1) unreasonable delay by the claimant and (2) prejudice to the defendant resulting from that delay.1 In the Matter of Riven Flamenbaum, the New York Court of Appeals, the state’s highest court, revisited laches.2

Significance of the Laches Defense in New York

As most readers are aware, a statute of limitations sets a deadline after which lawsuits are prohibited. The laches defense is not needed if the statute of limitations already bars a lawsuit. However, New York has a distinct statute of limitations for conversion in claims for artwork (i.e., acts excluding an owner’s rights, such as stealing or refusing to return artwork), which makes it a more hospitable forum for owners’ claims for lost or stolen art that can be decades old. Under the New York rule for claims by an owner to recover artwork possessed by someone else, the statute of limitations does not start to run until the possessor refuses a demand by the owner for the return of the artwork—the theory being that until the possessor has refused a lawful demand, she has done nothing wrong. (There are exceptions to this rule if the artwork no longer exists, has already been transferred to someone else, or was stolen and is in the hands of the thief). Furthermore, in New York, the expiration of the statute of limitations against any person does not extinguish the owner’s title. As a result, under New York law, a demand for the return of artwork that had been stolen or converted decades earlier could be within the statute of limitations.3 Such lawsuits may raise questions about whether the owner slept on his or her rights to a degree that is unfair to the possessor, who may have purchased the artwork in good faith, and for market value. In his defense, the possessor may assert a laches defense (i.e., that the owner unreasonably delayed making the claim, and this delay prejudiced the defendant).

New York Rule—Stringent Enforcement of Requirement to Show Prejudice to Defeat a Claim by the Original Owner

As discussed in our earlier essay, Flamenbaum presented an unusual reversal of the usual Holocaust-claim scenario. A German museum was asserting a claim for an Assyrian gold tablet stolen during World War II, against the estate of a Holocaust survivor, Flamenbaum. Flamenbaum had told his children that he bartered the tablet from a Russian soldier for cigarettes. During the estate proceedings, Rivenbaum’s son objected to the inclusion of the executor’s inclusion of the tablet in the estate accounting because the tablet had been stolen from the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin, and the son, on his own initiative, contacted the museum. At that point, the family learned the tablet was worth US$10 million.4 The museum claimed the tablet, and the estate, asserted a laches defense.

The Surrogate’s Court, which deals with probate matters, initially ruled for the estate, holding that the museum had unreasonably delayed its recovery efforts, and that the estate was prejudiced by the fact that Riven Flamenbaum was not available to testify. The Appellate Division reversed, finding that the estate had not shown that the museum had exercised a lack of due diligence by failing to report the tablet stolen to law enforcement or listing it on an international stolen art registry. The Appellate Division also found there was no prejudice to the estate from the museum’s delay—despite the fact that the estate’s principal witness, Flamenbaum, had died—because the estate had failed to show that the museum’s failures to act prejudiced the estate’s ability to defend its claim, or that the estate changed its position in reliance on such delay.

The New York State Court of Appeals, the state’s highest court, affirmed the Appellate Division’s award of the tablet to the museum, and provided some helpful guidance on two key elements on the laches defense.5

The first element of the laches defense is to demonstrate that the owner failed to exercise reasonable diligence to locate the missing work. The court of appeals implicitly found it reasonable that the museum did little if anything to seek the return of the tablet. It did not report the theft to any law enforcement agency, or list it on any database of stolen artwork. The court noted, seemingly with approval, that “the museum explained…it would have been difficult to report each individual object that was missing after the war.” The court of appeals also noted that under New York law, as a matter of public policy, placing the burden on owners to demonstrate due diligence in locating stolen artwork, and to foreclose the rights of that owner to recover property if it did not meet that burden, would encourage illicit trafficking in stolen art. This begs the question—why have this prong of the test if it is against public policy to require reasonable diligence from the owner?

Perhaps the answer is that the case involves admittedly looted art. (Indeed, the estate offered a separate “spoils of war defense,” which was rejected as “fundamentally unjust.”) The estate argued that if the museum had been more diligent, the museum could have discovered Flamenbaum’s possession of the tablet. But what if it had tracked down the tablet? The court pointed out that the family had noticed during Riven Flamenbaum’s lifetime that the tablet belonged to the museum. Moreover, the court held there was nothing Riven Flamenbaum could have done if he had been alive—the court stated that “we can perceive of no scenario whereby the decedent could have shown that he held title to this antiquity.”

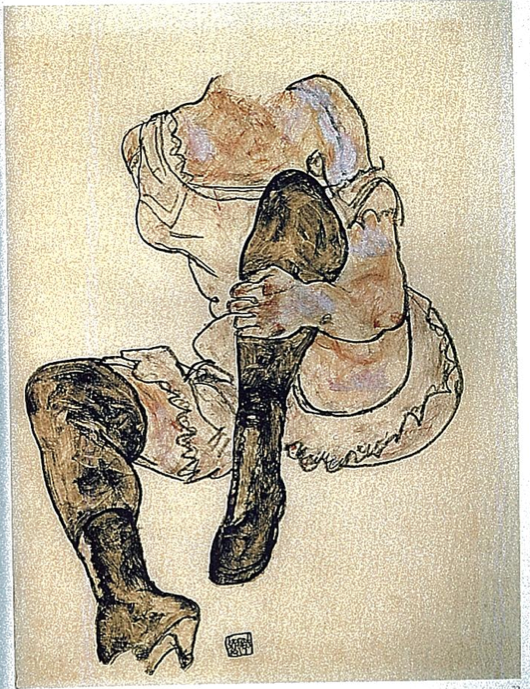

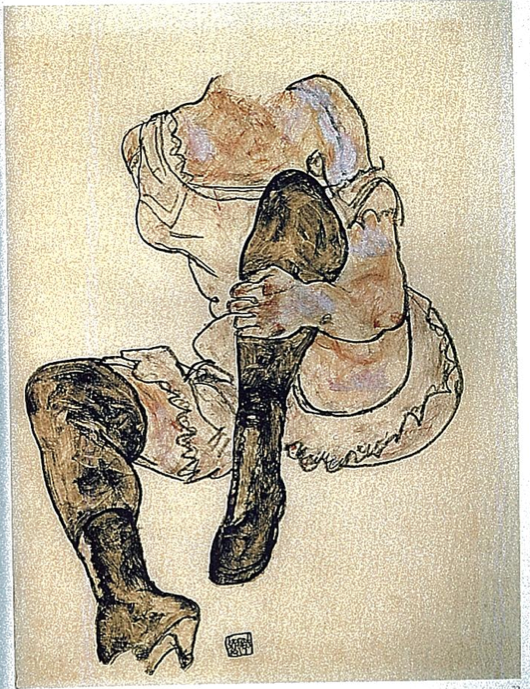

This is consistent with the decision by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in 2012, applying New York law. In that case, Bakalar v. Vavra, the court held the death of a witness would be prejudicial because that witness could have testified on the transfer of title to the artwork.6 David Bakalar purchased a drawing by Egon Schiele entitled Seated Woman with Bent Left Leg (Torso). The painting had once been owned by Fritz Grunbaum, a musician and art collector who died in a concentration camp. After the war, Grunbaum’s sister-in-law claimed to own the drawing and sold it in 1956. Decades later, distant family members asserted that they were properly the heirs of Grunbaum and claimed to own the drawing. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals held that Bakalar was prejudiced by the death in 1979 of the sister-in-law, who was the only person who could have testified as to whether she had received the artwork as a gift and therefore could have supported Bakalar’s chain of title.

In sum, it appears that unless the possessor has a plausible potential claim to have lawfully acquired good title, a 60-year delay in asserting a claim is permissible, even if the owner did almost nothing to locate the missing artwork. Conversely, it seems that unless a possessor can demonstrate that the original owner’s delay eliminated evidence that could have supported its claim of good title by the defendant, there is no viable laches defense.

New York, NY

January 2014

Judith Wallace

Carter Ledyard & Milburn LLP

Notes

1 See Solomon R. Guggenheim Found. v. Lubell, 77 N.Y.2d 311, 321 (1991).

2 Matter of Flamenbaum, 2013 N.Y. Slip Op. 7510 (Court of Appeals, Nov. 14, 2013).

3 See the spring 2012 issue of Spencer’s Art Law Journal for a comprehensive discussion of the this rule and the public policy reasons for protecting true owners of lost or stolen art, originally set forth in the landmark 1991 Court of Appeals decision in Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation v. Lubell. See Judith Wallace, “New York’s Distinctive Rule Regarding Recovery of Misappropriated Art After the Court of Appeals’ Decision in Mirvish v. Mott,” Spencer’s Art Law Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Spring 2012), available at http://www.clm.com/docs/7045310_1.pdf.

4 Kieran Crowley & Chuck Bennett, Holocaust Survivor’s Kin Can Keep $10M Relic, N.Y. Post, Apr. 6, 2010.

5 Matter of Flamenbaum, 2013 N.Y. Slip Op. 7510 (Court of Appeals, Nov. 14, 2013).

6 Bakalar v. Vavra, No. 11-4042-CV, 2012 WL 4820801 (2d Cir. Oct. 11, 2012).

Editor’s Note

This is Volume 4, Issue No. 3 of Spencer’s Art Law Journal. This issue contains two essays, which will become available by posting on artnet, starting in February 2014.

The first essay (Getting Good Title to Art You Purchase, as (a) a Collector, (b) an Art Dealer, or (c) a Bit of Both) addresses the title investigation required when there are “red flags” about good title.

The second essay (Sometimes it’s Not Too Late to Recover Your Art. Laches: The Stealth Defense Revisited) updates our analysis of the defense of laches available to a holder of art against a claim for return from the original owner.

Three times each year (since 2010), issues of this journal address legal questions of practical significance for institutions, collectors, scholars, dealers, and the general art-minded public.